THE JOURNAL

Shoe mussels from Valdivia with rock green sauce. All photographs by Mr Cristóbal Palma, courtesy of Phaidon

How Mr Rodolfo Guzmán’s Boragó changed the perception of Chilean food.

Up until a few years ago, you’d have been hard pressed to find high-end cuisine in Chile that was actually Chilean. Due to the difficulty of procuring, transporting and preserving of local ingredients, not to mention a lack of knowledge about them, wine was the only thing of note that came from the nation’s natural larder.

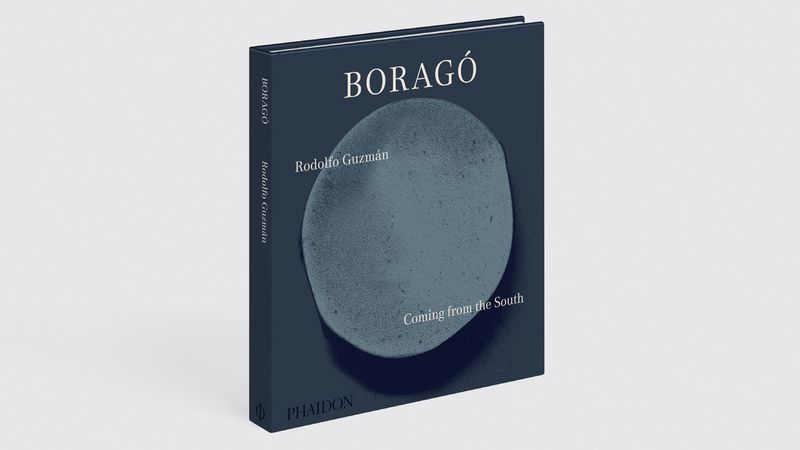

That all changed, however, when Mr Rodolfo Guzmán opened Boragó, a Santiago restaurant that is now ranked among the 50 best in the world. This November, we’re being given an opportunity to discover Boragó’s short but colourful history via a new book, authored by Mr Guzmán and published by Phaidon. Boragó: Coming From The South will be the first high-end gastronomy cookbook in English from a Chilean chef. This would be impressive in any case, but is particularly poignant with Mr Guzmán because it tells the story of how the chef revived Chilean ingredients that other domestic chefs had neglected in favour of imports.

Atacama Desert, Chile

“I realised that this was a huge opportunity,” writes Mr Guzmán. “All the restaurants in Santiago were working with frozen seafood and meat – not a single restaurant was making use of indigenous ingredients, such as mushrooms, wild fruits, seaweeds, halophytes (succulents that grow near the coast), or plants, and I could not understand why… As Chilean chefs, we weren’t rooted to our land or culture.” To combat what he saw as a gross oversight, Mr Guzmán built a network of foragers that allowed him to harvest these underused culinary components. “When I first started to serve these new ingredients at Boragó, luxury ingredients were being imported; whatever came from within Chile was considered to be of lesser quality,” he writes. “When diners from Santiago asked about the country of origin of the ingredients we were serving, we would explain that the ingredients were locally grown, and they couldn’t believe it. We were championing a new Chilean cuisine and ideas never before explored.”

Still, back in 2006 when the restaurant opened, the conservative local culinary press was not impressed, and “continued to insist that what we served was fodder for cows… There was no interest in trying Chilean food with seasonal endemic ingredients; it was considered boorish and cheap. High-end food was something that came from outside the country.” The geographical isolation of Chile, plus the ruthless wave of disparaging articles from local journalists meant that the restaurant’s early days were tough: “Many nights we only had about two guests, and sometimes there were none.”

Rica rica ice cream and chañar concentrate

Mr Guzmán persevered, and eventually began to garner a little recognition from further afield. Thanks to some international press from the food writer Mr Andrea Petrini (who writes a glittering paean to Mr Guzmán in the book’s introduction), the restaurant’s reputation snowballed, and due to a consistent if ambitious menu, empty chairs were soon fully booked for months in advance.

As well as the restaurant’s biography, the book contains an impressive glossary of unheard-of ingredients native to Chile: algae-like bushes from the Atamaca Desert, for instance, or chocolate mushrooms that smell like cocoa and grow next to the mountains, as well as sea urchins, white strawberries, and Patagonian berries. For even the worldliest gastronome, Boragó’s offerings are surprising.

Looking through the photographs of plates arranged with wild flowers, charred vegetables and balls of ice cream suspended from the nest-like sculpture of rica rica twigs, it becomes abundantly clear Boragó’s dishes aren’t the kind of thing that look easy to replicate. You are, however, invited to try: the book also features 100 recipes from Mr Guzmán’s tasting menu.