THE JOURNAL

The Cat Returns (2002). Photograph by Allstar/Alamy

Otakus of the world rejoice! From this week, Studio Ghibli lands on Netflix and over the next three months, animated features from the beloved Japanese studio will be rolled out on the platform. We can just hear the shrieks of glee around the world. From Ponyo and Howl’s Moving Castle to some of Ghibli’s lesser-known masterpieces, there is a vivid treasure trove of magical filmmaking waiting to be binge-watched. With that in mind, a few dedicated Ghibli fans in the MR PORTER office have taken the opportunity to share some of their favourites.

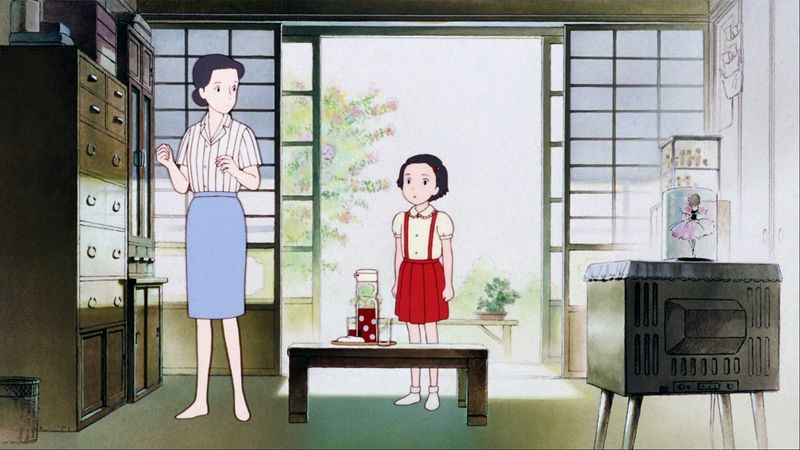

Only Yesterday

Only Yesterday (1991). Photograph by Allstar

I must have been barely a teenager when my dad came home one day with a copy of Spirited Away from Blockbuster (god, Blockbuster!) – I remember watching it and feeling like it was absolutely the best thing I’d ever seen in my tiny little life. The colours! The music! The Radish Spirit! I promptly devoured as much of Mr Hayao Miyazaki’s masterpieces as though I was No-Face set loose in Yubaba’s bath house. It was a few years later, though, that I saw Only Yesterday. Directed by Mr Miyazaki’s collaborator and Ghibli co-founder, the late Mr Isao Takahata, Only Yesterday was released in 1991 and tells the story of a young woman working in a Tokyo office who visits the Yamagata countryside and has to make the choice between staying there or returning to her life in the city. Outwardly, it’s a quieter film than much of Studio Ghibli’s oeuvre; the magic here doesn’t come from spirits or anthropomorphised animals, but instead from the childhood memories and demons that shape our decisions in both career and love as we move through life. If you’re going through a quarter-life crisis (or really, just a constantly ongoing one), I can’t recommend anything more.

Princess Mononoke

Princess Mononoke (1997). Photograph by Allstar

The day I finished my university finals, I was expecting a huge weight to fall from my shoulders. Instead I felt wild, lost and depressed, so I went to my room, closed the curtains, put a mattress on the floor and fired up my DVD player (remember those?) with Princess Mononoke. It’s, let’s say, an interesting film to watch in a fragile mood. There’s the Freudian nightmare of the opening, in which a village is attacked by a writhing demonic turd. There’s the gorgeous renderings of forests filled with sweet but creepy semi-translucent spirits. And then there’s the overall message: a FernGulley-esque wail of desperate resistance against the forces (still very much at large in the world today, thanks very much) that would trample over nature in the name of profit. I was, obviously, sobbing in a foetal position by the end of it all. And if the same doesn’t apply for you, perhaps capitalism has gone too far?

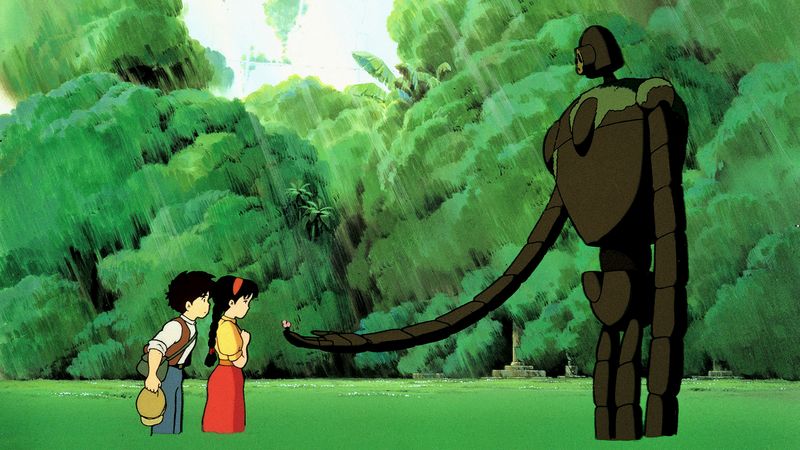

Laputa: Castle In The Sky

Laputa: Castle In The Sky (1986). Photograph by Allstar

There was none of this Netflix when I were a lad. In fact, there were but four channels, all with a curfew, and the latter of these had only just been launched. If you missed something, in the ephemeral world of broadcasting, it was gone forever. This didn’t stop me scouring the schedules and sniffing out fringe animations from other countries that, despite having a massive impact on their respective domestic markets, would hardly register a blip on the radar of the English south coast’s uniformly dull suburban cultural desert. Firm favourites saved on VHS tape included Hugo The Hippo, a psychedelic 1970s Hungarian feature financed by Fabergé’s (yes, that one) short-lived film production company, and Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King, a 1979 Chinese effort that gained enough of a cult following outside of the family bungalow to warrant its own Google Doodle in 2014. But when Castle In The Sky hovered into view, collective minds in the Merrett household (well, those under 10) were blown. A Mr Jonathan Swift-ian tale of orphans and robots, proto-steampunk air pirates and flying islands (whoa!), the details are perhaps sketchy today, but the visual language and sense of adventure remain implanted in my brain. Indeed, I’m still looking for that illusive castle in the clouds. But now, when I find my son laughing hysterically at weird Korean cartoons he’s unearthed in the furthest corners of Netflix – even though he’s too young to read the subtitles – I think, “That’s my boy”.

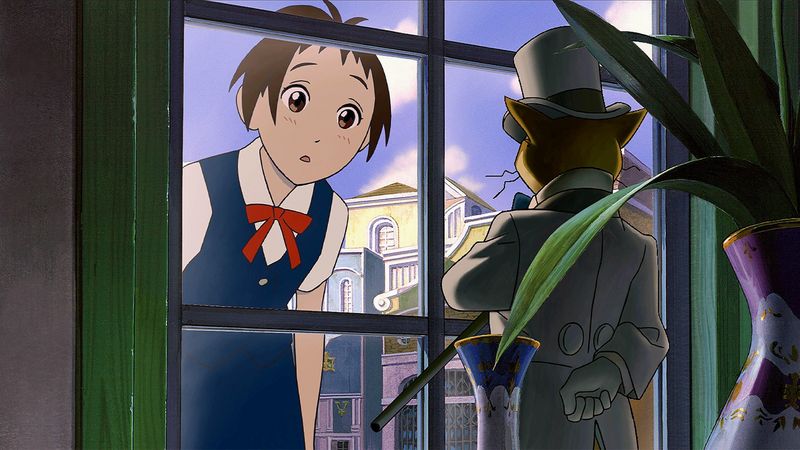

The Cat Returns

The Cat Returns (2002). Photograph by Allstar

It’s a matter of debate whether my fierce affection for this film – a Whisper Of The Heart spin-off – has more to do with my appreciation for Studio Ghibli’s aesthetic and sentimental brilliance or a lifelong desire to acquire my own personal army of felines. There are, it should be noted for the not-a-cat-person contingent, lots of cats in this movie. But there’s much more to it for those whose retinas have been burned by a recent film with similar subject matter. Namely, an immaculately turned-out cat wearing a top hat and tails, a surprise appearance by Mr Tim Curry, who voices the Cat King in the English-dubbed version, and the important lesson that not all cat movies are created equal. OK, maybe it is just cats. But at least it’s not Cats.

Pom Poko

Pom Poko (1994). Photograph by Photo 12/Alamy

I was raised on a diet of cookie-cutter kids’ movies cranked out by the Hollywood entertainment-industrial complex, so watching my first Studio Ghibli film – Spirited Away – felt like stumbling around in a darkened room. It wasn’t so much the unfamiliar animation style or the subtitles that left me bewildered, but the near-complete absence of Western cinematic tropes. Sure, there were parallels with stories such as Alice In Wonderland or The Wizard Of Oz – young girl enters magical realm, leaves with life lessons learned – but that’s pretty much where the similarities ended. Instead of the heroes, villains and sidekicks I’d grown to expect, there were grotesque, faceless spirits spewing up gallons of vomit, humans transmogrified into pigs… the whole thing was just so weird. This overwhelming sense of otherness, of feeling somehow unmoored and adrift is, for me, the essential attraction of Studio Ghibli’s movies. They go to places Western animation wouldn’t dare, places it wouldn’t even think to go. It follows, then, that one my favourite Ghibli movies also happens to be one of the strangest and most fantastical of the lot: Pom Poko. Written and directed by Mr Takahata, it’s the story of a group of raccoons who find their forest habitat under threat from suburban development and decide to retaliate. I’ve been told that to fully appreciate the story you really need an understanding of the raccoon’s place in Japanese folklore. Alternatively, you could do what I did and just muddle along, spending the entire movie wondering what on earth is going on.