THE JOURNAL

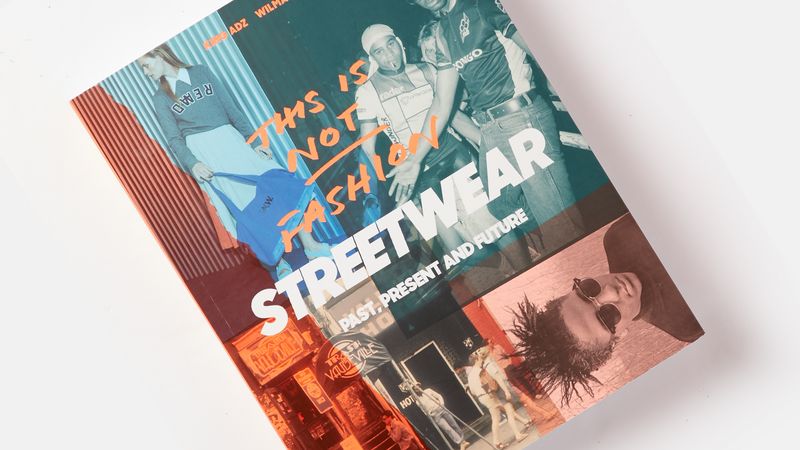

A new book This Is Not Fashion explores how the streetwear aesthetic was created.

In his influential 1979 book Subculture: The Meaning of Style, Mr Dick Hebdige writes, “The word “subculture” is loaded down with mystery. It suggests secrecy, masonic oaths, an underworld. It also invokes the larger and no less difficult concept ‘culture’”.

These words still ring true today. The world of streetwear – the delta into which all subcultural tributaries flow – often feels cultish, rife with in-jokes (did you know Deliveroo jackets are the new DHL T-shirts on the resale market?) and arcane anti-cultural references.

Mr Adam Stone (aka “King Adz”) – perhaps a contemporary descendant of Mr Hebdige – is well-placed to understand both culture and subculture. An ex-advertising executive, his new book: This Is Not Fashion: Streetwear, Past Present And Future, co-written with fashion graduate Ms Wilma Stone, connects the dots between various subcultures and highlights their relationship with streetwear.

You may already know the headline moments in the streetwear story (Mr Shawn Stussy’s eponymous label, Nigo’s A Bathing Ape, Nike, adidas, Palace, Supreme, Off-White…), not to mention the influence of major subcultures like punk, hip-hop, rave and skateboarding. But the evolution of streetwear also has a few less-obvious influences. Here are five we learnt after reading Mr Stone’s book, which is published today.

The army

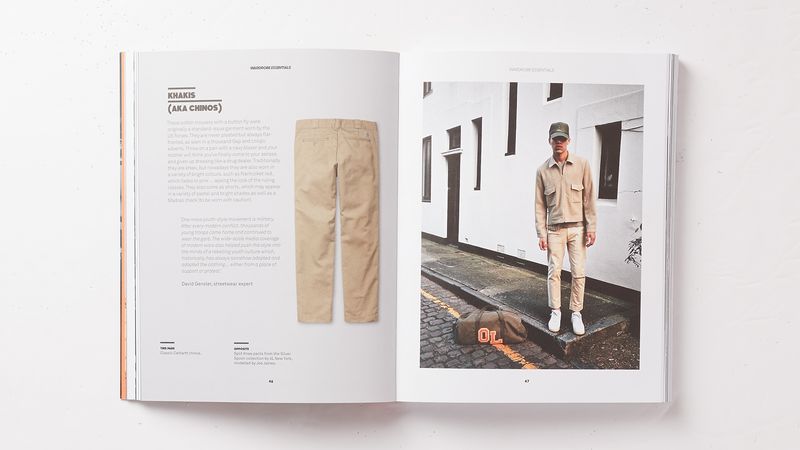

Left: Classic Carhartt chinos. Photograph courtesy of Carhartt. Right: Split Knee pants from the Silver Spoon collection by òL New York. Photograph by Mr Dexter Navy/òL New York

Sometimes it seems like streetwear has created its very own army. But it’s easy to forget that the actual military played a significant role in its evolution too. From iconic pieces like the MA-1 bomber jacket to camo print and khaki fabric, the clean, utilitarian features offered by military uniforms have always translated well to the urban environment. Perhaps there are political undertones too: Mr Stone quotes cultural historian Mr David Gensler, who says military-inspired style finds itself in the minds of youth culture after every modern conflict as either “a form or support or protest”.

Sailing

If you were fortunate enough to attend any sort of rave in the UK during the 1990s, you might have noticed something interesting. In among all the baseball caps and Reebok Classics, there was a real penchant for windcheaters – particularly from premium sailing brands like Tommy Hilfiger, Nautica, Helly Hansen and Henri Lloyd. Perhaps the sailing jacket found popularity with what Mr Stone refers to as the “modern mutation of the Northern Dresser, usually with a Liam Gallagher haircut” as it was lightweight, easy to stuff into a bag, colourful and also aspirational. This somewhat exclusive hobby found popularity with streetwear tribes on both sides of the pond. As Mr Stone says, “a million homeboys” all sported sailing jackets too.

Rivets

“Denim,” Mr Stone writes, “is one of the founding mothers of streetwear.” It was part of every subcultural uniform from the ripped jeans of the punks to the flares of the hippies and the baggy fits that were revered in the world of hip-hop. Today, denim is as streetwise as ever, with jackets from brands such as Yeezy remaining particularly popular. The iconic fabric’s story, however, begins in the late 19th century in America, when a Nevadan tailor named Mr Jacob Davis was asked to make a pair of trousers that wouldn’t fall apart. A few copper rivets lying nearby caught his eye, and promptly found themselves strengthening the trousers’ construction. Days afterward, Mr Davis partnered with Mr Joseph Levi-Strauss to meet exploding demand for this simple, hard-wearing cotton twill garment. The rest, as they say, is history.

The British upper class

Clockwise from left: Ralph Lauren Tennis ad, circa 1985. Photograph by Ralph Lauren; René Lacoste. Photograph courtesy of Lacoste; oversized tennis jumper from Preen by Thornton Bregazzi on the Catwalk. Photograph courtesy of Preen by Thornton Bregazzi; classic Oxford cable-knit cricket sweater; Temple University letter sweater, early 1960s. Photograph by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images

Oxbridge-educated, elegantly attired Brits didn’t know it at the time, but their leisurewear uniform of colourful sweaters and polo shirts was hot for appropriation on the streets of Brooklyn in the 1980s. Originally sold to preppy Harvard types as the outfit of the American dream, Ralph Lauren’s Polo brand was based around old-money pursuits like tennis, rugby and sailing. Crews of inner-city youths like Brooklyn’s Lo-Lifes – who were notorious for “racking” (stealing) hundreds of thousands of dollars-worth of ultra-rare Polo pieces – put their own streetwise spin on the image. As Mr Stone writes, it’s a “glorious example of how brands get subsumed into an alien culture”. The preppy fingerprints of the British upper class are still all over the streetwear scene today.

eBay

In the world of streetwear, scarcity is a valuable commodity: a truth that brands like Supreme exploit all too well. And – with limited-run “drops” selling out in seconds, the resale market is vast (and lucrative). This secondary market was born on forum message boards in the 1990s, but received a nitrous boost with the advent of eBay in 1995 – a new marketplace that let anyone, anywhere, flip their rare streetwear pieces for serious gains. Today, the reseller market has turned from “static clunky shops”, in the words of Mr Stone, “to slick content channels”. Sites like Grailed, Too Hot or Wavey Garms, for instance, give streetwear-hungry buyers a second chance to find ultra-sought-after pieces from brands such as Supreme and Palace – and shrewd sellers an opportunity to participate in one of the fastest-moving, most exciting markets on the planet.