THE JOURNAL

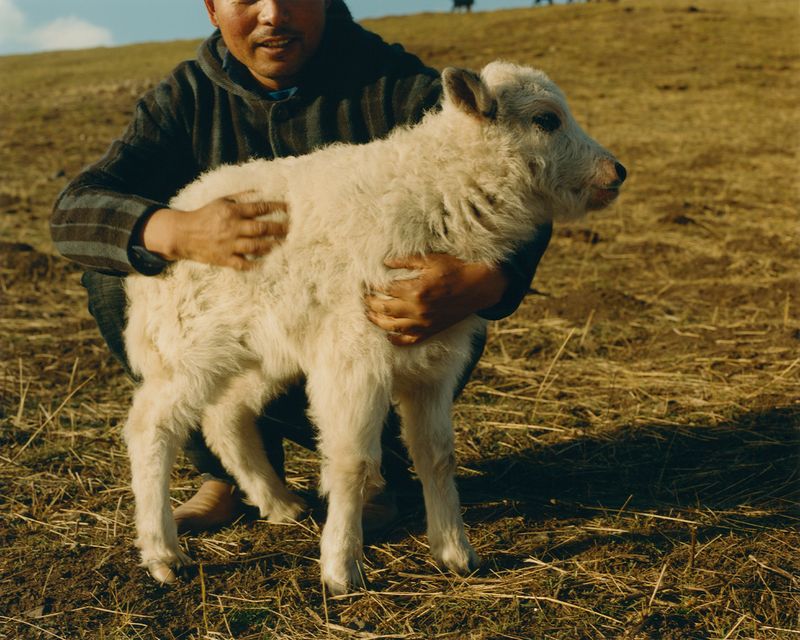

Photograph by Ms Nikki McClarron, courtesy of Norlha

The jovial, mid-interview chuckle of His Holiness the Dalai Lama or a particularly hirsute Mr Brad Pitt scaling snow-capped Himalayan peaks in Seven Years In Tibet might be the closest most of us have come to experiencing Tibet. But even the name of this mysterious, high-altitude land of rugged massifs, sweeping grasslands and devout Buddhist rituals evokes a sense of arcane magic.

For Ms Dechen Yeshi, CEO and co-founder of Norlha, the call of the plateau is much more than a romanticised ideal. It’s in her blood. Born in France to a Tibetan father and an American mother, Yeshi embarked on a cultural research trip to her ancestral land in 2005, following her graduation, and ended up putting down roots there for good. She soon became aware of the lack of economic opportunities the nomadic Tibetans faced. Their forefathers had crisscrossed the plateau for centuries, following a way of life that gave back to the land – a way of life that now found itself at odds with a rapidly changing world.

It was this Tibetan concept of giving back that sowed the seed for Norlha, the lifestyle brand founded by Yeshi and her mother, Kim, in the nomad settlement of Ritoma in the Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, 10,500ft above sea level. “It was crucial that we sourced a locally available raw material and brought all the training to the area to support the community,” says Yeshi.

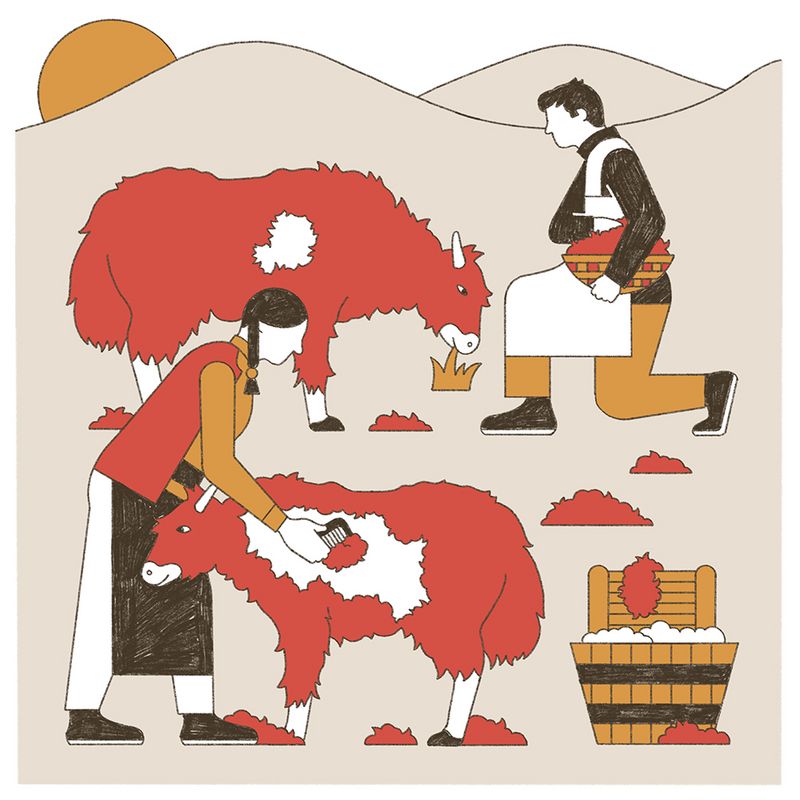

Grazing yaks on the Tibetan landscape. Photograph by Ms Nikki McClarron, courtesy of Norlha

That raw material came from what had been the lifeblood of human sustenance in the region – the yak. These shaggy, high-altitude cousins of the cow are known as nor, which is also the word for “wealth”, a legacy of a cashless society in which livestock were a measure of worth and to which Norlha owes its name, “god of wealth”.

“The fabric made from the thick outercoat of the yak had long been used for tents, but it wasn’t suitable for clothing because it’s quite heavy and coarse,” says Yeshi. “We found other types of yak fibre hadn’t really been explored to their full potential.” She and her mother turned their attention to the khullu, the ultra-fine, downy hair from the underbelly of baby yaks, which they shed naturally on the grassy plains in spring.

This cloud-soft fibre cocoons the animals from the glacial winters on the plateau when temperatures drop as low as -50°C. As you’d expect, it’s an exceptional insulator, but, despite its plush handle, it’s also hardy. “It’s just as soft as cashmere, but it has a more masculine feel to it, more of a heft,” says Yeshi. “You can be a little rougher with it and go outdoors in different weathers and you know it’s going to hold.”

This rough-and-tumble alternative to cashmere shares similar properties to the king of yarns, but it has a distinct advantage. While the insatiable appetite for cashmere has led to the over-zealous breeding of animals and the decimation of grasslands on the Mongolian steppe where the goats feed in hoards, this industrial, battery production isn’t part of the yak’s story.

“We only gather what the animal gives up naturally to the plains as it sheds its yarn as the seasons change,” says Yeshi. “We don’t breed or own yaks. These are free-ranging animals.”

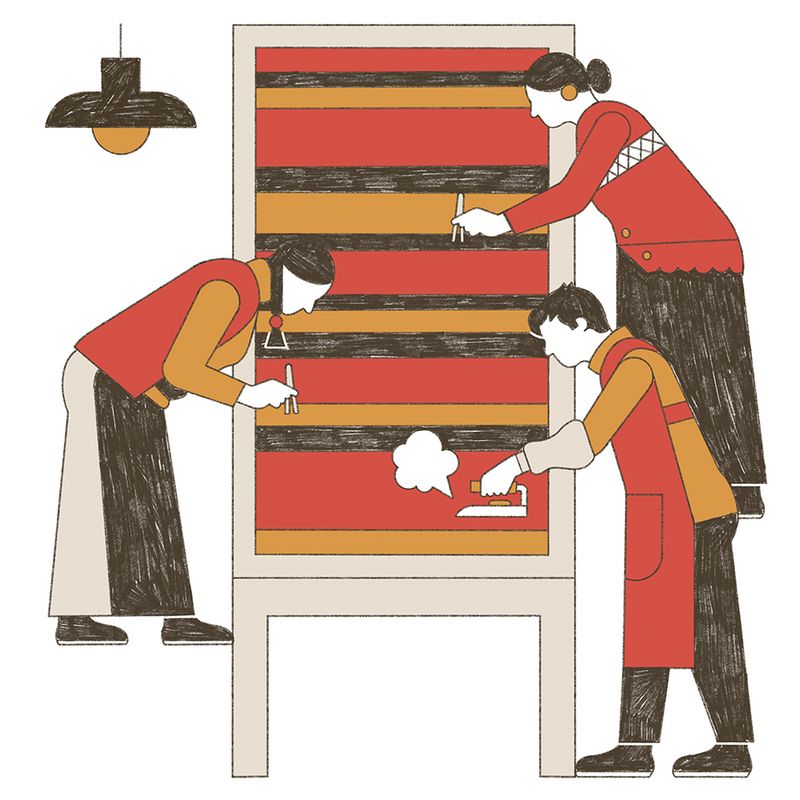

An artisan spinning yak khullu fibre into thread. Photograph by Ms Nikki McClarron, courtesy of Norlha

Finding a raw material was just the first hurdle. “Being a nomadic society, there wasn’t a deep-rooted craft in weaving,” says Yeshi. “There were no looms.”

To rectify this, the team travelled to Nepal and India, where they came across vintage looms that were built to the same specifications as the looms shipped out by the British during the Raj. “These old British-style looms worked much more smoothly with the yak wool than newer ones, so we imported them and adapted them,” she says.

Two trainers were also brought from Nepal to teach the local nomads how to work the looms. “With these older looms, we need to make sure that the team of 10 work in perfect harmony, with feet, hands and shuttle in perfect rhythm,” says Ms Wandi Kyi, who has been a Norlha weaver since 2007. “I trained for six months, after which I could weave a scarf, but it was only after 10 years that I felt qualified as a weaver.”

The brand also uses felting, a local technique distinct from weaving, which involves rolling the yak fibres back and forth in the hands to form a textile. It’s this method that’s used to make most of MR PORTER’s range. The skill of this technique lies in the ability to feel the consistency of the fabric with your fingers as it is rolled out.

“Although I had felted sheep wool as a young woman, there was a big difference in the attention to detail with the Norlha designs,” says Ms Dolma Tso via an interpreter, a nomadic felter at Norlha since 2010. “I trained for four months. The more I felt the cloth with my hands, the more I learnt to fine-tune my sensitivity to the quality of the felt.”

The end result is a beautifully soft, refined yet rustic-looking cloth, which makes heirloom-worthy blankets ideal for draping over your sofa or shoulders on cool evenings. In an uncertain modern world that’s as challenging as the seasons on the plateau, we could all do with the comforting embrace of a cosy blanket.

The lifecycle of a yak hair blanket

Curious to know what it takes to turn yak hair into a sophisticated throw for your home? Follow the production line to see how a Norlha Felt Trails blanket makes it from field to sofa.

Day 01.

8.00am: yak hair harvest

In late spring, baby yaks, known as yeko, begin shedding their downy underlayer of khullu. Before the herd heads out for a day’s grazing, they’re gently combed to minimise loss of the fibre to the herby grasslands. Additional hand-gathering is done on the plains as the animals moult during feeding. The raw khullu fibre is then sent to a specialist eco-friendly laundry in Xining in western China to be washed thoroughly in purified water to dislodge dirt particles before dyeing.

Day 02.

9.30am: khullu carding

The raw khullu is returned to the workshop in Ritoma where it is carded. This is a mechanical process where the fibre is fed onto large rollers set with thousands of wire pins to align the hairs and make it into a consistent “web” of fibres that can be worked into a cloth. “Obtaining a carding machine to deal with khullu was difficult,” says Yeshi, “so we found a small family-run Italian firm that had been making them for generations and commissioned one specially.”

Day 03.

8.45am: Laying the groundwork

In the workshop felting room, which is lit by natural light, three women begin arranging the multicoloured khullu fibres in a stripe formation in accordance with the Felt Trails design on a large, flat table to a 160cm x 200cm specification, to allow for shrinkage during production. “The most challenging part of the process is working on felt pieces with several colour variations,” says Tso. “It requires a lot of precise calculation.” The fibre is then dampened with water and soap, which acts as a binding agent, matting the fibres together as the blanket is made.

9.30am: rolling up

The three women, positioned along the length of the table, begin rolling and flattening out the fibre with their hands to form the blanket over the next seven hours, taking a break at 10.15am and stopping for lunch at 12.30pm. The skill of this process is all in the touch. “At this stage in the hand-rolling, we need to pay special attention to make sure the thickness of the felt remains even throughout the piece, the desired weight is exact and the suppleness of the felt is neither too stiff nor too elastic,” says Tso.

12.00pm: pattern checks

The multicoloured fibres of the blanket need constant monitoring to get the desired results. “Working on felt pieces with several colour variations is the most challenging,” says Tso. “We need to check regularly during rolling that the stripes are settling to the required width and that the different coloured fibres are not intermixing. We need to halt the rolling process and unravel each time we check.”

Day 04.

9.00am: cleaning

After the rolling is complete and the blanket is formed, it is washed to remove the soap and to make sure the fibres have “set” so the blanket retains its shape and dimensions with any future washings. It is then left to dry for six to seven hours before it is ironed, labelled and any remaining imperfections are picked out by hand during final quality control checks. “We don’t apply chemicals to make the blankets excessively soft,” says Yeshi. “It’s all about what you can achieve with natural hand-applied processes. When you touch or wear the fabric, people say you can feel a little part of the plateau on you. There’s an honesty to it.”

Day 05.

5.00pm: delivery

The finished Felt Trails blanket is shipped to a warehouse in Lanzhou in northwest China and collected by MR PORTER. After placing your order, it arrives at your home for you to unbox and drape over your sofa, bed or even your shoulders on a cool alfresco evening.

Illustration by Mr Andrew Joyce