THE JOURNAL

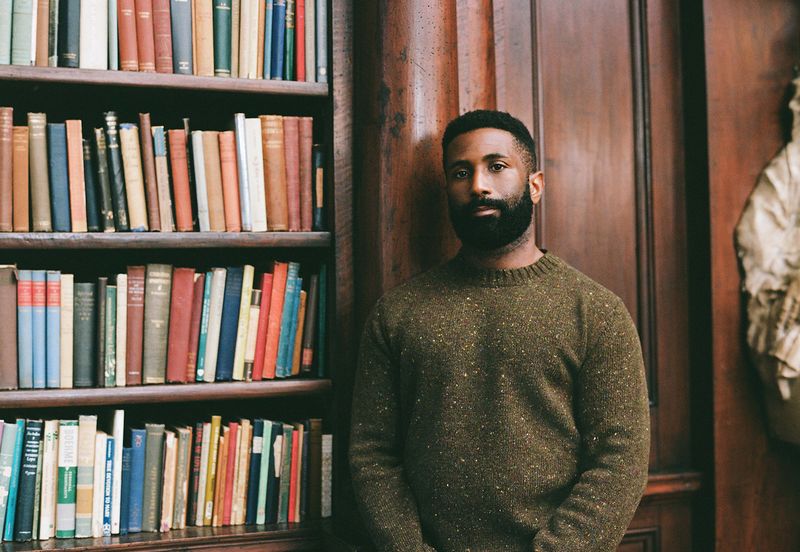

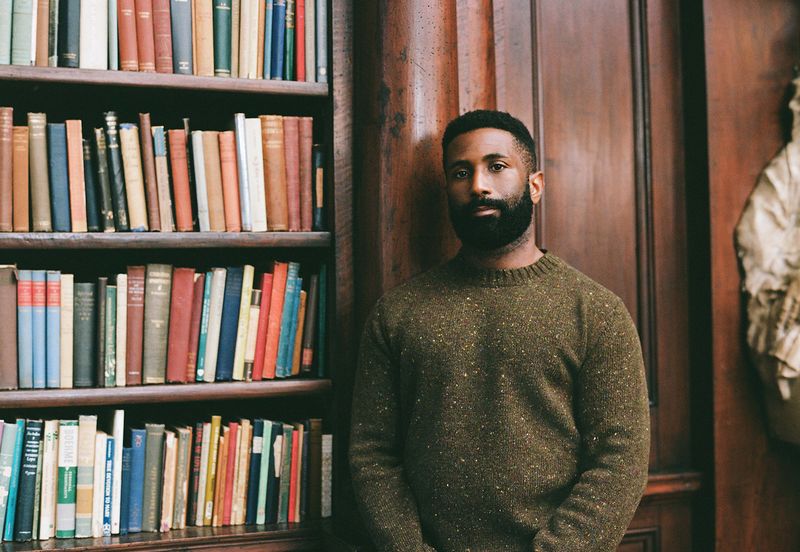

Mr Wesley Morris

How do you drive a point home in the era of the hot take? If anyone knows, it’s these guys.

It’s a Thursday in the autumn of 2018. At least two major political upheavals are in full swing, news of which is streaming across our social media timelines. New York City is gridlocked in every direction, spilling over with dignitaries and their entourages, who are in town for the United Nations General Assembly, and Mr Wesley Morris, the Pulitzer Prize-winning culture critic for The New York Times, is putting the final touches to a blockbuster essay called “The Morality Wars”, which is about the political imperatives of art appreciation in the US.

In the coming weeks, as various political crises sprout and mushroom across the landscape, Mr Morris’ essay describing our collective criticism of art – which he suggests must take into account a work and creator’s entire backstory, intent, and political awareness, as much as the work’s artistry – will hit the web, streams and newsstands. And to great fanfare and some disagreement, competing for space in many a dinner-party conversation. In other words, it matters. People will engage with it, struggle with it, applaud it, repeat it. Mr Mark Harris, for example, a cultural critic who often writes for New York magazine, will tweet, “This is a brilliant and challenging essay by @Wesley_Morris that did not make me feel ‘Yes to every word of this!’ but did make me want to sit down quietly and think hard.”

It is oddly refreshing and thrilling that even in this cluttered, hot-take-ridden media landscape, the presentation of an idea or perspective on our current cultural climate can startle and challenge us to see something in a different light or think more deeply. Ideas are everywhere, but they’re still valuable. It’s a fact that’s perhaps obvious, but can’t be overstated.

So, on that same Thursday in 2018, as the daily discourse is threatening to set our brains on fire, we talk to a few of our favourite writers and editors, voices of calm in our fiery times, to cut through the flames and see if we might pick up a little wisdom along the way.

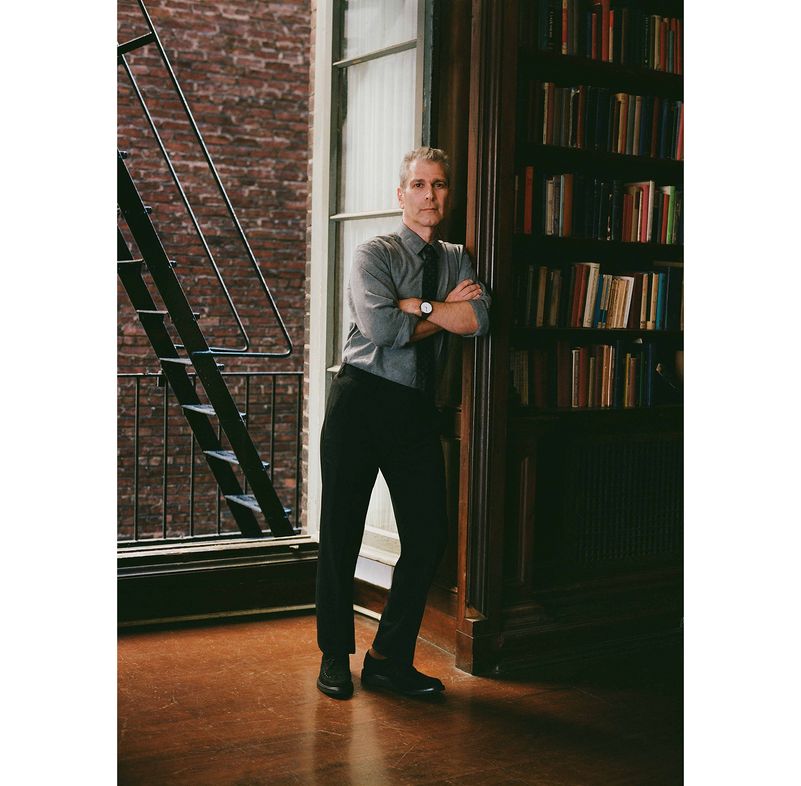

MR JAMES MARCUS

Editor, writer

You may have noticed that much of the conversation generated by independent magazines of late is not the good kind. Publishers with a contrarian point of view on, say, the #MeToo movement, have used their platforms to support some questionable “not all men” narratives, and the responses to the essays they have printed have been devastating to their publications. This is a phenomenon that Mr James Marcus, in his tenure as editor-in-chief of Harper’s magazine, experienced when, despite his objections, the magazine’s publisher published a poorly received article railing against “Twitter feminists” to the general disdain of the publishing community. So fervent and public were Mr Marcus’ objections to the piece, and the manner in which it was pushed through, that when he was subsequently fired, Twitter basically stopped and applauded him for his efforts. Not that any of that is exactly comforting to him now; although being right, and indeed on the right side of history, has to feel pretty good. Therefore, there is no one better positioned to talk about the mission of independent magazines today than Mr Marcus, whether that mission is to operate with great urgency to affect the greater discourse, or tarry in their little eddies, satisfied with presenting a diversity of voices and viewpoints.

“Certainly, the pressure to do cultural and journalistic work in the outside world is much more intense since, say, 2016, and for good reason,” he says. “You would seem crazily obtuse to pretend that nothing is going on. Not that there were no problems in the past that a magazine like Harper’s might try to ameliorate. And, of course, Harper’s does have a long history of running politically engaged writing of all kinds, but it also has a history of attending to the left-field corners of American life and going against the current in that way. One of the things I always liked about the magazine, and that excited me about it when I started working there, was that it was supposed to be a magazine free from doctrine, both politically and aesthetically. I was on a panel about politically engaged writing at a long-form non-fiction conference in Pittsburgh a couple of years ago, soon after Trump was elected, talking about the extent to which you should be politically engaged. Some of the other panellists said there is no choice now. The culture is on fire and if you’re not writing about that fire, you’re asleep. I basically agree with that, but I am uncomfortable handing out prescriptions to writers about what they should write about. You just can’t bend talents to any particular culture moment. They have to approach it in their own way. One of the other people actually said, ‘This is 2016. You can’t write about birches any more,’ taking a shot at Robert Frost. And I just said, ‘Look, if you live in a birch forest, that may be what you end up writing about.’”

Mr Marcus is writing a book on Mr Ralph Waldo Emerson, who, he says, is “horribly pertinent” to our conversation about political engagement. “Issues having to do with imperialism, slavery and big money were quite alive back then [in Mr Emerson’s time]”, he says. “And they’ve hardly become ossified in the present moment. But when you look at Emerson and the coterie of geniuses and oddballs surrounding him, you see many different models for how a writer should politically engage or not. It’s been really useful for me to look at Emerson, Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott and that whole constellation of people, some of whom were intently engaged in retail politics, in speechifying, canvassing and trying to grapple directly with social issues. Some of them, like Emerson, inhaled a purer version of the transcendentalist vapours and thought, ‘If you’re going to have a revolution in consciousness, why should you picket?’ You know, why should you worry about voter registration when a sort of cognitive and existential lamp is going to go on in the head of people? And of course, that didn’t happen. There was no revolution in consciousness, so that’s sort of a beautiful dream, but even Emerson became a fiery abolitionist speaker and engaged in other ways with political issues of the day.”

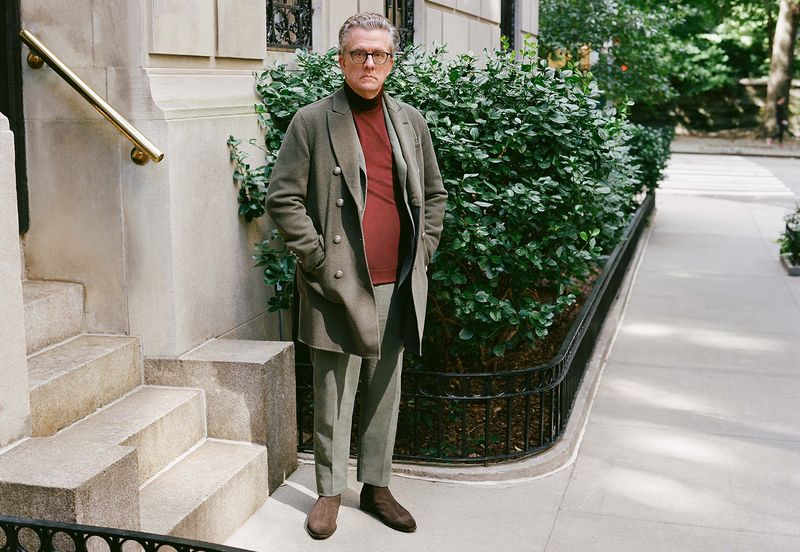

MR KURT ANDERSEN

Writer, co-creator and host, Studio 360

If anyone embodies and best demonstrates the range of possibilities available to the public intellectual in modern-day American society, surely it is Mr Kurt Andersen. As the co-founder (with Mr Graydon Carter) of Spy, the knowingly satirical magazine and ürtext of much internet writing, Mr Andersen covered the media elite of late 1980s New York and Los Angeles with wit and devastating epithets (“Kurt did the mean stuff and I did the funny stuff,” Mr Carter has said. “Or was it the other way around?”), even as his success in doing so elevated him to establishment status. He has written regular columns for The New York Times, The New Yorker, New York magazine and _Time (_where he was also editor-at-large from 1993 to 1996); written for stage, film and television; been a guest on TV shows Charlie Rose and Late Night With Conan O’Brien; authored or edited nearly a dozen books, the most recent of which, Fantasyland, is subtitled How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History. These days, his day job is host of Studio 360, the Peabody Award-winning radio show he helped create for Public Radio International.

“I guess each of us does whatever we think we do best, most interestingly and/or usefully,” he says. “In my case, it’s commenting, critiquing, satirising, plus explaining, as in Fantasyland. And as a novelist, I guess, doing the things that fiction does: revealing and illuminating by imagining and inventing. But enough gerunds!”

He’s also funny. From the column he wrote in his high-school paper to editing the Harvard Lampoon while studying, all the way up to and including the faux-Trump memoir he published last year with Mr Alec Baldwin, everything Mr Andersen does has a little comic English on it. “As to whether humour has strategic utility for persuading or convincing,” he says. “I can’t really say.”

Of the various platforms available to us these days, appearing on TV, he says, “is mostly a means to an end, the end being to encourage viewers to read my books and articles. Radio and podcasts allow for longish, nuanced, occasionally significant conversations. And Twitter allows what Twitter allows – instantaneous comment and wisecracks and some whiffs of ‘community’.” But, despite our hardening dogmas and algorithmic silo-ing off into philosophically aligned groups in mutual agreement, he still sees the value of viewpoints and conversation across communities. “I think minds do change,” he says. “I know mine does.”

MR WESLEY MORRIS

Critic-at-large, The New York Times, and co-host, Still Processing

“We’re talking less about whether a work is good art but simply whether it’s good – good for us, good for the culture, good for the world,” Mr Morris wrote in his essay “The Morality Wars”. “This might indeed be a kind of social justice. But it also robs us of what is messy and tense and chaotic and extrajudicial about art. It validates life while making work and conversations about that work kind of dull.”

Mr Morris, who is at work on a book-length essay about “the performance of blackness”, as he describes it, has a terrific knack for finding footholds in the present cultural conversation, footholds from which he’s able to propel himself back in time and across media in order to synthesise several strands of our experience to make big diagnoses. And no one does it better. From his time writing film reviews at _The Boston Globe – _where he won the Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 2012 – then at Grantland and now at The New York Times, where he really covers the waterfront, Mr Morris, whether writing about the power of the late Ms Aretha Franklin or the sartorial choices of athletes, writes personally and specifically, as if to an audience of one.

“I just feel like there are things in my brain that I kinda want to figure out,” he says. “Or things in the world that bother me, or things that I love. And there’s a version of criticism that I like where it doesn’t really matter what the thing is that you’re writing about. You wind up doing some larger critical thinking, no matter what. For my entire professional life, that is how I approached criticism.”

Once a piece is complete, though, Mr Morris is happy to let it go, doesn’t hover too protectively, nervously or egotistically on the timeline to suss out the response to something he’s written. “Although I do feel a certain obligation to engage with something like this recent piece, so I will happily talk through some of this stuff with people,” he says. Which makes sense. In his writing, and on the Still Processing podcast he co-hosts with Ms Jenna Wortham, Mr Morris communicates with the candour, earnestness and playfulness of a dream dinner-party guest. “I talk a lot to people about stuff,” he says. “I just don’t do it on the internet. I also do like getting into arguments with people. And I like letting other people talk, and then you respond to what they’re saying. Which does not seem to me to be radically different from how people comport themselves on Twitter. It’s just that – and I’m sure there’s psychology that would back me up on this – it is kind of useful in having an argument to have your full faculties. Like, in a letter, you have your full capacity as a writer to make an argument and to argue against, in support, or whatever. And I don’t know that a tweet storm... First of all, it’s called a tweet storm, like, I don’t know. What do you do about that?”

MR JOHN FREEMAN

Poet, founder and editor of Freeman’s

For much of the past decade, Mr John Freeman has been the literary world’s international man of mystery, jet-setting to literary conferences like a character out of a Mr Roberto Bolaño novel. From at least 2009, when he published his first book, The Tyranny Of E-Mail, and throughout his tenure as editor of Granta magazine from 2009 to 2013, the American writer, poet and critic travelled between London and New York as frequently as every other week. But after editing a book on the results of climate change and its consequences (the third in a series of books he’s edited on economic disparity for Penguin), he’s found it more difficult to hop on a plane and increase his own carbon footprint. Not that he has slowed down in his search and celebration of disparate voices from all over the world.

“Politically, algorithmically, we are living in highly polarised times,” he says. “And these divisions simplify complex problems. Literature, to me, is the opposite of simplicity, even when it’s written in a clear, lucid style. Great literature, to me, celebrates and explores complexity. So, I think it would be a mistake to ask it to change a person’s mind on a particular occasion or about a particular issue. It probably can. What it can do more consistently and artfully, though, is turn on a consciousness. It can make the questions we don’t even realise we’re not asking more apparent. It can give solace in feeling less alone in knowing and having such questions. This is why I think we need to talk about great books so often when we read them. Great books make clear to us some of what we already know, but perhaps don’t hear or say, and then show us things we do not know. It’s in that combination that literature feels like life. It’s in this way that a book can make a community.”

One of the principal contributions of Freeman’s, as with Granta before it, is its creation of community, both in the gathering of writers in each biannual table of contents and in the body of readers and listeners who come to hear the pieces within it read aloud. “Which is why I want to go and hear books read aloud,” says Mr Freeman. “And why I participate in so many public events. It’s not about promotion. It’d be cheaper just to give Freeman’s away. Those events are about preserving a conversational space, about protecting a public space for curiosity. I had a bookstore launch this week with four writers from the new ‘Power’ issue: Nimmi Gowrinathan, Nicole Im, Deborah Landau and Aleksandar Hemon. They had a fantastic conversation. I’m pretty sure this group of writers has never shared a stage before and so part of Camus’ edict, I think, has to extend to who is part of a conversation, who gets put together.”

(Note: I’d been mentioning to each of the gentlemen above Mr Albert Camus’ definition of a conversation as being the meeting point between two people willing to change their mind. I asked each of them whether this was a state of being that even existed any more and they all, in their own way, seem to think it definitely does and is a great, achievable aim of the daily discourse, of dinner party gatherings and of their work.)

“A dialogue in public, or between essays by two different writers, can make a bridge between the world of politics and the world of literature, the universe of context and the literature written in that context,” says Mr Freeman. “So as long as I can, I’m going to be out on the road, looking for things I don’t know and for people to look for it with me.”