THE JOURNAL

“I don’t really want to be anywhere else in London, to be perfectly honest,” says Mr Chris Johnson. He’s the landlord at The High Cross, a pub housed in a former public convenience in Tottenham, north London, but he’s talking about the other place he works and, in fact, over the past year, has spent much of his time: his allotment. “Once you close the gate, it doesn’t matter what’s happening outside. You just focus on the plot.”

At East Hale Allotments, it’s not hard to get your bearings – you can see the City from here, Canary Wharf looming to the south, beyond the canal. A visit is soundtracked by the hum of the North Circular, and bleeps from reversing forklifts. “You just block it all out,” Johnson says. “It’s in the background.”

“We’re surrounded by the old Victorian reservoirs on one side, and then warehouses and industrial estates on the other,” says Mr Sam Gledhill, who runs his own architectural studio, who has a neighbouring plot. “We are on the fringe of London, in the Lee Valley. We’re in the middle of everything.”

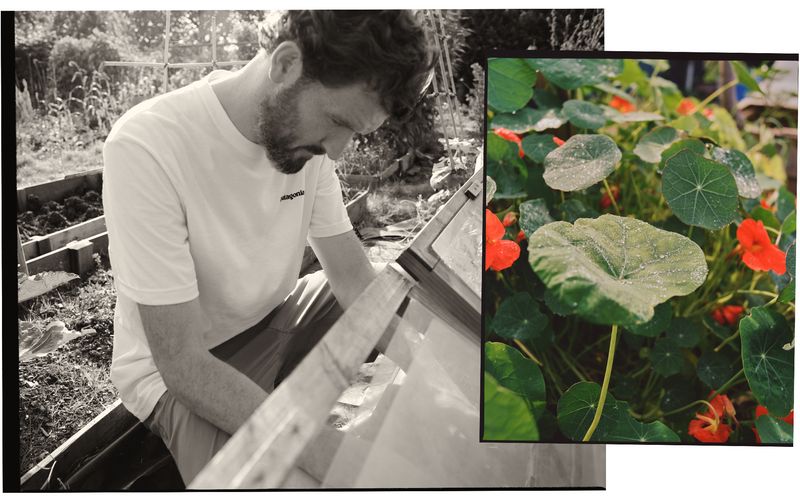

Left: Mr Chris Johnson and Ms Rosamund Ward. Right: Ms Katie Drysdale, Mr Sam Gledhill and their son

To tire of London is to tire of life, as Mr Samuel Johnson once famously posited. But for many residents today, there are pockets of the city that become essential precisely because they offer respite from the demands of living here. And you don’t have to go far. Perhaps surprisingly, green space makes up almost half of London; vast parks and patches of woodland, as well as rows of private gardens. But there is a particularly British feel to the allotment; even the name – American readers will be more familiar with community gardens. Similarly, Gledhill notes that within the Turkish community at East Hale, the plots are referred to as gardens.

The seeds of the modern allotment were sown in the Norman conquest, then the numerous Inclosure Acts from 1604 onwards, when landownership in England and Wales fell into increasingly fewer hands, and the agricultural and industrial revolutions, with a growing workforce now cut off from the countryside. The “guinea gardens” that sprang up on what was the outskirts of Birmingham in the 18th century are seen as the beginning of the urban allotment, with land set aside for city workers.

When he spoke of the city, the cultivation that Samuel Johnson had in mind was of the mind. But on the 36,000 allotments still spread across London, growth is something far more tangible. And, if you’re lucky, edible.

“I grow a little bit of everything,” Gledhill says. “Primarily soft fruit – anything that can go in a smoothie – beetroots, beans because they grow well in England.” Also a lot of courgettes – possibly too many, he says. “And each year, I do something a little bit odd. This year, I tried summer squashes. They make great gifts.”

Johnson admits that his partner, Rosamund, does most of the growing on their plot. She in turn claims that the results are mixed. “We got loads of carrots one year and then nothing – even in the same spot. Aubergines were quite fun. I didn’t expect them to grow and they did.”

“Anything that’s a bit more Mediterranean, once you have a bad patch of weather, you’re screwed,” says Katie, Gledhill’s fiancée.

“I’d like to grow a melon one day,” Gledhill adds, wistfully.

Photographed here as part of our Go Out series, it is advice as much as proximity that has brought the two couples together. “I ask Sam for tips on vegetables,” Rosamund says. “Why mine are half the size of theirs. I think we got to know each other a lot more during the lockdown.” Conversation drifts between work and home lives, but tends to come back to the allotment. “Being vegetable enthusiasts, it’s generally compost, propagating, watering – that sort of thing.”

“I do most of the landscaping,” Johnson says. Testament to the enduring popularity of the allotment, the couple were on the waiting list for five years before securing a plot, actually a half plot. “When we first got it, it was completely overgrown. I’ve been building beds and putting up pergolas and just trying to make it safe for a child.”

Both couples have young boys. And while Johnson and Rosamund’s son is now old enough to get into trouble, Gledhill and Katie’s son was just 10 weeks old when this video was shot. “Being around nice children, it takes the edge off a bit,” Gledhill says of being a parent and the fears that come with it. “We’re looking forward to taking him down and getting him involved, definitely,” Katie adds. She admits to melting a bit at the sight of their friends’ son with a watering can.

“Rosamund’s parents are really keen gardeners,” Johnson says. “My mum as well. And I think that’s really important for us to pass that on to our son.”

“Katie grew up in Melbourne and she had grounds around her house,” says Gledhill. “I’ve seen photos – they’re absolutely beautiful. And my parents owned a tearoom, with the seating area in the garden. The garden had to stay well maintained. There’s always been something edible growing, whether it’s just herbs or something a little bit more substantial.”

“You go into a flow state,” Katie says of working on the allotment. “I do, anyway. We get here in the morning, really early, and leave at 2.00pm starving. You just lose track of time.”

Time isn’t so much lost here as well spent. “If you’ve got a long shift ahead of you, it’s nice to get outside beforehand,” Johnson says. “I like the repetitiveness of tasks. Turning the soil, propagating, planting and sowing, then maintaining, watering. Then eventually you harvest… it’s a process that’s really quite simple and natural.”

“Sometimes, I’ve found the working environment quite frustrating,” Gledhill adds. “Often, you don’t get the rewards that you were hoping for. But with an allotment, you really can put in hours and you get rewarded for it.”

It can be hard, sometimes back-breaking work, but the effort pays off. And not just in terms of what it provides for the dinner plate. Johnson says that the labour it takes to maintain a plot makes you stronger. “You look at some of the old boys around here and they’re in their seventies and eighties, and they look great. And you think, ‘That’s what I want to be like when I’m an old man.’”