THE JOURNAL

Neom, The Line, 2022. Image courtesy of NEOM

The recent reveal of The Line in Neom – a 172km long megastructure, half a kilometre tall and 200m wide, faced with mirrored glass and bisecting the deserts of north-western Saudi Arabia – has revived the spectre of the monumental urban experiment.

But grand urban schemes, rich with spectacular structures, have been a symbol of power since antiquity. Radical rebuilding schemes – whether occasioned by politics or aesthetics – brought visions such as Mr Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s Paris and Sir Edwin Lutyens’ New Delhi to life, cementing the connection between power and civic might. The 20th century’s major drivers were war and bulldozers, the latter usually following hot on the heels of the former. War, in particular WWII, coincided with the modernist vision of renewal and reinvention in the name of better social parity. How successful this was very much dependent on luck and location, but the movement’s heyday was auspiciously timed to coincide with Europe’s urgent need for reconstruction.

The modernist era was awash with grand plans for grand spaces, guided by solo voices and visionaries convinced of their own genius and innate understanding of the myriad, multiple complexities of urban planning. Several generations of “masters” attempted to reshape the skylines of the 20th century with their personal visions. From Mr Frank Lloyd Wright’s lifetime obsession, Broadacre City, to Le Corbusier’s 1930 Ville Radieuse concept, to Mr Buckminster Fuller’s 1959 New York Dome over Manhattan, architects and designers thought big.

“Architects never stopped dreaming, eventually coming up with a series of vast, self-contained conurbations that ostensibly placed megastructural architecture at the service of society”

Le Corbusier’s vision was especially influential – it paved the way in part for the new Brazilian capital city of Brasília, planned from scratch by Messrs Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, and Joaquim Cardozo – but thankfully never realised. The Ville Radieuse called for living units to be concentrated in high-rise blocks surrounded by parkland, maintaining the density of a traditional city while maximising green spaces. At various times, the iconoclastic architect suggested his housing units might usefully replace large chunks of Paris and Manhattan, even building a couple of prototype blocks, notably the Unité d’habitation in Marseilles, to illustrate what a vast, self-contained housing block should look like. Unhappily for his legacy, his imitators only took one part of his plan as inspiration – the high-rise – and used the sprawling parkland as space to build more of them.

Architects never stopped dreaming, eventually coming up with a series of vast, self-contained conurbations that ostensibly placed megastructural architecture at the service of society. Unfortunately, the vision of society they were striving to serve was car-centric and pre-digital. And these proposals continued to peddle this fatally skewed equation in ways that feel deeply uncomfortable to modern sensibilities. Speculative projects of the era include Mr Kenzō Tange’s plan for Tokyo, developed along with Messrs Kisho Kurokawa and Arata Isozaki in 1960, which envisioned the city spreading out into Tokyo Bay – a strict separation of business and residential zones and interlocking highways and light rail connected the sail-like concrete structures.

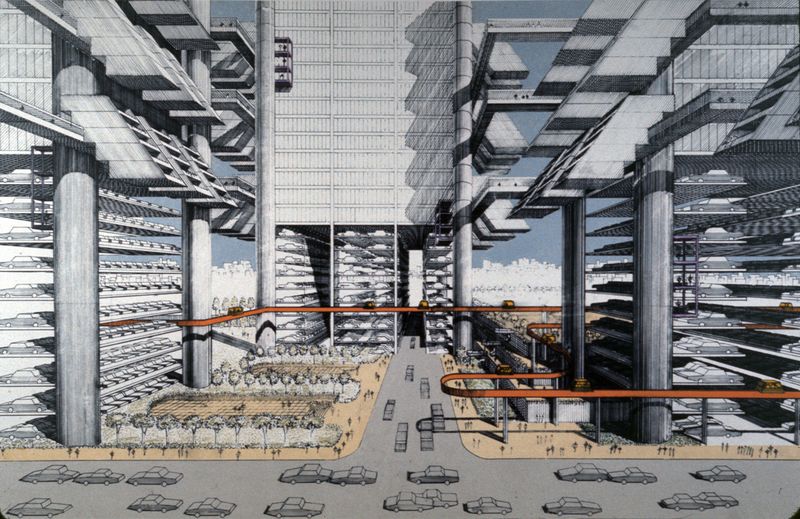

Mr Paul Rudolph, Lower Manhattan, 1967. Image courtesy of Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture.© Estate of Paul Rudolph.

In New York, the architect Mr Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway proposed the air rights above the freeway as a space for development, envisioning a snaking, stacking concrete superstructure threading through the city. In the UK, the glass company Pilkington sponsored a vision by the mild-mannered modernist Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe. Motopia was a garden city overlaid with a grid of buildings, all with highways on their roof. Intersections were marked with circular buildings beneath roundabouts.

Motopia’s theme of an all-encompassing plan was at least tipping over into satire, acknowledging the impossibility of such an undertaking. Nevertheless, planners from around the world persisted on imposing new roads and infrastructure on already creaking cities. Half a century later, and it’s widely agreed that the car – particularly the motorway-borne car – has no place in a dense, walkable city.

Although schemes went ahead everywhere from London to Boston, the most egregious were thwarted by a mixture of concerned civic groups, ruinous costs and common sense, leaving only remnants of these automotive monuments to deface cities around the world, from London’s stubby motorways, the road tunnels beneath Madrid, or long-demolished expressways in San Francisco.

“Fifty years in the making, ‘City’ has made a recluse of its creator and generated a lasting mythos within the art world”

The spectacular imagined worlds of Corb, Lloyd Wright and others spoke volumes about these men’s unshakeable belief in their abilities to dictate how others should live their lives. These urban visions were patriarchal and technocratic and ultimately dictatorial, despite their veneer of organic, nature. preserving planning. Corb eventually got to live out his planning dreams in the Indian city of Chandigarh, working alongside Mr Pierre Jeanneret and the British architects Mr Maxwell Fry and Ms Jane Drew. His far-reaching visions for Algiers and Paris were a dodged bullet and remained on the drawing board.

Likewise, Lloyd Wright never built on anything on the scale of Broadacre City or his ambitious plans for Baghdad. However, the American brought his remarkable vision into every one of more than 500 projects that he completed during his seven-decade career – almost a small city's worth of landmark buildings.

The megacity should have been abandoned, a thoroughly discredited strand of design that saw fit to filter massive complexity through the ego and mythos of its creators. But it was not. Neom has seemingly brought us full circle. The Saudi Arabian project, driven by the nation’s crown prince and de facto ruler, Mr Mohammed Bin Salman, has been gestating for at least five years, in which time the brickbats have outnumbered the bouquets.

Mr Michael Heizer, City, 1972. Photograph by Mr Ben Blackwell. © Michael Heizer Triple Aught Foundation 2018

The latest swathe of lavish renders – cinematic in their scope, Oscar-baiting in their fictive ambition – coincided with the completion of another visionary city on another continent. This city, however, was never intended as a bustling metropolis. The artist Mr Michael Heizer's monumental piece of landscape art occupies a carefully guarded private tranche of Nevada. “City” is an angular assemblage of rock, concrete and sand, nearly 2sq km of landscape blasted and sculpted into the shape of a pristine yet empty and abandoned urban plaza for an unnamed civilisation. Fifty years in the making, “City” has made a recluse of its creator and generated a lasting mythos within the art world.

“City” is pristine, and Heizer will ensure it stays that way. Each day, just six lucky people (like golden ticket holders touring a chocolate factory) will get to experience these bleak monoliths and alien angles for themselves. The work harks back to the lifeless drawings and models of the purist modernist supercities, where life is conspicuous only by its absence. “City” can be read as a critique of those utopias-as-dystopias, just as Superstudio’s bold piece of 1970s-era high-concept paper architecture, the “Continuous Monument”, took contemporary architecture’s worship of geometric minimalism to its literal extreme, encircling the globe with an endless grid.

The mirrored cliff of Neom is hardly different in ethos or scale. It is paired with exotic imaginary interior vistas that look like the greebled retro-futures of Mr Syd Mead spliced with the lush sun-dappled vegetation of Mr Thomas Kinkade, all filtered through Midjourney’s AI art software. It’s a video game city, nothing less, designed to capture the attention of a generation brought up on limitless virtual worlds. Transferring these pixels into reality will cost an estimated half a trillion dollars and an army of construction workers larger than the world has ever seen.

Anyone who has dabbled in the original SimCity or its more sophisticated successor, Cities: Skylines, will know that a successful city – even a virtual one – is an organic, living, breathing beast that evolves over generations of trial and error, while responding to local conditions both environmental and economic. In other words, a utopia can’t just be magicked into existence with a hefty splash of ego, an economically precarious and hence eager workforce and countless millions in contractor fees.

The only thing Neom has in common with the stark, dusty plazas of “City” is that it is overwhelmingly driven by a single man. One is art; one aspires to utopia. “City” works because all it has to do is exist. Neom, on the other hand, has to do everything – and doesn’t appear to have learnt any lessons from the past. For if nothing else, last century’s abandoned megastructural visions taught us to be abundantly cautious in the face of such promised architectural perfection.