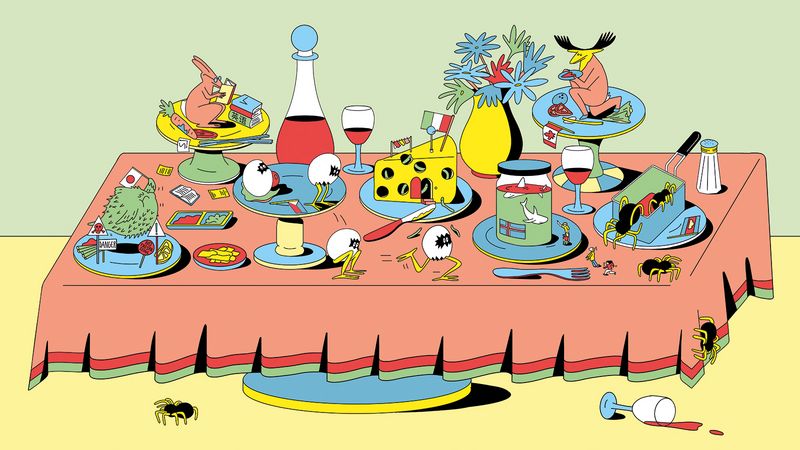

THE JOURNAL

In our modern age of convenience, where supermarkets stuffed with vacuum-packed meats crowd city streets, the taste for unusual cuts and hard-to-come-by delicacies has waned. Accessibility and speed of preparation have come to trump culinary imagination, perhaps particularly in the UK and the US. Still, humans evolved not to waste their quarry and in many parts of the world, traditions survive that celebrate our marvellous cultural heritage. Often this means meat dishes, sometimes offal that, shamefully, is often thrown away in many Western countries. Sometimes it means preparation practices that are stone-cold dangerous. So, read on as we present our buffet of the world’s most interesting and adventurous dishes – but be warned, they are not for the faint of stomach.

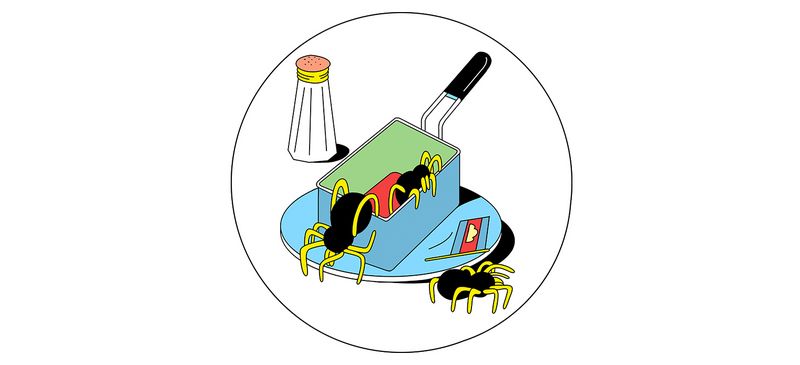

Deep-fried tarantula, Cambodia

Insects and arachnids have long been heralded as the protein source of the future that will help to relieve the planet of the pressures of intensive meat production. You don’t need to tell that to Cambodian spider connoisseurs. For generations, tarantulas have been lured from their forest burrows, separated from their fangs, killed and grilled in banana leaves or deep-fried. Poverty brought about by the bloody regime of the Khmer Rouge turned the delicacy into a staple. Since then, tourists and TV chefs have discovered the potential bragging rights in fried spiders, which has led to a shortage in some areas, but they remain a mainstay of markets across the country. After a few minutes of frying, the tarantulas are said to taste slightly crab-like with pleasantly crisped extremities.

Where to eat it: market stalls at Skuon aka Spiderville, 47 miles north of Phnom Penh, or at Bugs Cafe in Siem Reap.

Blowfish, Japan

In 1774, Captain James Cook noted that some of his crew became seriously ill after eating a tropical fish. The pigs to which the men had fed the remains of the fish were dead by morning. The sailors were lucky. They had eaten pufferfish, or blowfish, a species notable for its inflatable body and the high levels of tetrodotoxin in its internal organs. The neurotoxin is used in nature as a defence against predators. Its effect on humans is gradual, horrific and generally terminal. Even a tiny amount causes numbness, then seizures, vomiting and extreme stomach pain. Total paralysis soon follows, and the victim can remain conscious until respiratory failure brings about death a few hours later. There is no antidote. Yet in Japan, fugu, as the fish is known, is a delicacy served with a frisson by specially trained chefs. Fatalities still occur, usually after amateur preparation, but you could also end up with a delicious meal. You have been warned.

Where to eat it: Usukifugu Yamadaya, a specialist fugu restaurant in Tokyo with three Michelin stars.

Casu marzu, Italy

There aren’t many plates of food on which mould is welcomed (hello, roquefort and stilton), but on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia, the ageing of cheese is taken to putrid extremes. Rather than simply introducing bacteria to the maturing process, makers of casu marzu (it translates helpfully as “rotten cheese”) cut off part of the rind of the pecorino-like wheel so that flies may lay their eggs in the cheese. These hatch into larvae, which then get to work on the fats in the cheese, breaking them down in an enhanced process of fermentation. The resulting cheese is rich and silky soft, and the maggots are consumed alive. Born of necessity centuries ago (why let pesky maggots spoil your cheese?), casu marzu became part of Sardinia’s culinary heritage until the EU banned it on safety grounds in the 1990s. Eat it at your own risk. (We certainly don’t recommend it ourselves.)

Where to eat it: it’s now illegal to sell it commercially, but ask a few older home cooks and you’ll find someone still making it.

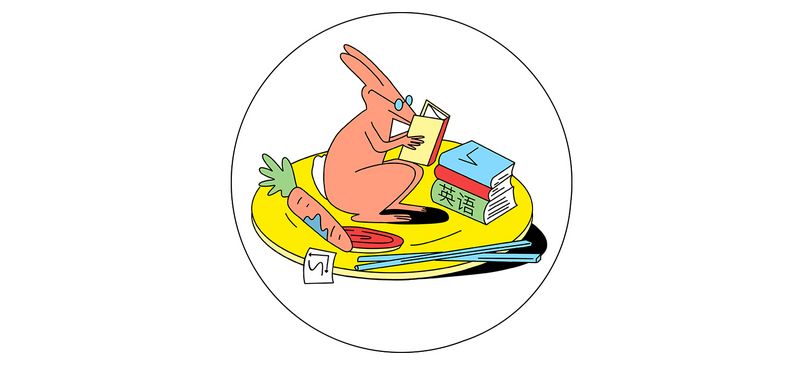

Rabbit brains, China

There are few cuisines that are as carnivorously completist as those found within the wildly varying regions of China. In Sichuan, famed for its spices and mouth-numbing peppercorns, rabbits’ heads are in particular demand. Marinated for hours in a fiery broth according to centuries-old recipes, the heads are served whole to diners armed with plastic gloves at restaurants and night markets in Chengdu, the province’s capital. There is scant meat to be nibbled, but the traditional source of joy for the diner comes later – if you’re squeamish, look away now – when the lower jaw is yanked free and used as a spoon with which to scoop the brains from the cranial cavity. Rabbit heads are so highly sought after in Sichuan that restaurateurs now import them by the thousand from as far away as France.

Where to eat it: night markets in Chengdu or at Shuangliu Laoma Tutou, a well-known central restaurant.

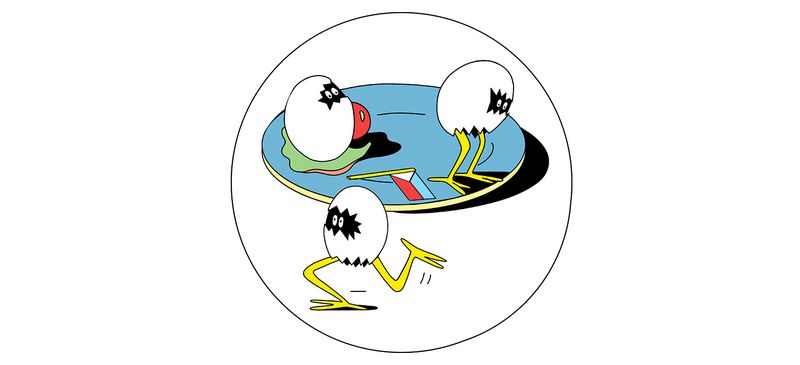

Balut, Philippines

As a child, you may have feared that an egg cracked for an omelette might contain a chick rather than white and a yolk. In parts of the Philippines, that’s the whole point. Balut looks from the outside like any other duck egg. But these eggs, a national dish, have been fertilised and then incubated for a couple of weeks, traditionally in sun-warmed sand. The eggs are then boiled or steamed. Cracked at the fat end where an air pocket helps with the shelling, the contents are then scooped out and eaten with salt. Levels of crunch depend on incubation time. The delicacy is controversial, not least outside the Philippines. Thousands of New Yorkers signed a petition in protest when a restaurant in the city hosted a balut speed eating contest.

Where to eat it: food stalls and restaurants in Manila or at Maharlika, a restaurant in Manhattan.

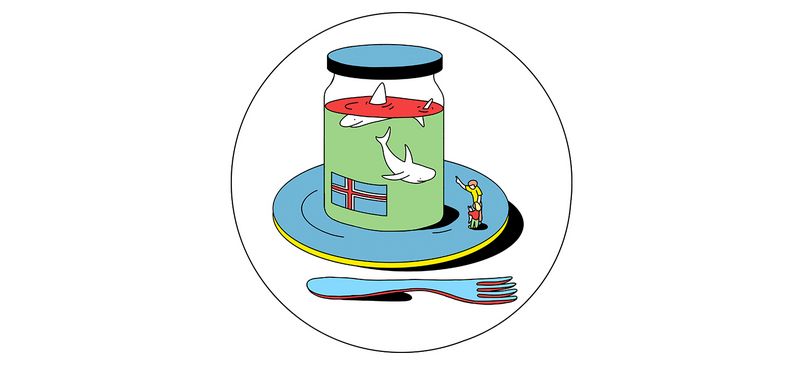

Fermented shark, Iceland

The late Mr Anthony Bourdain ate a lot of out-there delicacies in his career as an international food correspondent. There were seal eyes and beating cobra hearts and duck embryos (see balut, above). But there were, he said, three things he would never touch again: plane food, Namibian warthog rectum and Icelandic fermented shark. The latter dish, known as hákarl, remains a celebrated feature of the country’s midwinter festival. The shark meat is cured and hung to dry for months, during which fermentation produces high levels of ammonia. Sold in cubes in vacuum packs, the meat can be chewed on and chased with a shot of brennivín, a type of schnapps. First timers are advised to hold their noses and attempt to repress their gag reflex, which is unhelpfully triggered by the ammonia.

Where to eat it: Kaffi Loki, a popular traditional restaurant in central Reykjavik.

Stuffed moose heart, Canada

There is something reassuringly familiar and festive about a large lump of meat nestling in a roasting tin, perhaps stuffed with something herby. In parts of Canada, that cut may just be a giant heart. Moose roam wild in broad swathes of the country, where hunters’ freezers are piled high with traditional cuts of rich moose meat. Rarely wasted, the deer’s heart – roughly the size of a football – can be roasted whole for a gamier dish. Should you wish to make one at home, you’ll first need to soak your heart in a bucket of water to draw out the blood, trim its fatty bits and then, after a good browning, stuff its multiple chambers with something sagey. Bigger hearts will take up to three hours to roast before being sliced and served with potatoes and vegetables, perhaps on a Sunday.

Where to eat it: find a huntin’ and fishin’ type, perhaps in Newfoundland, and get a lunch invitation.

Illustrations by Ms Elena Xausa