THE JOURNAL

Mr Ernest Hemingway and Ms Hadley Richardson in Switzerland, 1922. Photograph by Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Ms Lesley MM Blume’s new book details a lesser-known ingredient in Mr Ernest Hemingway’s early literary success: antisocial behaviour. Here’s a few reasons why you wouldn’t have friended the American novelist in a hurry .

It’s common knowledge that Mr Ernest Hemingway was one of the early 20th century’s most pioneering and influential authors. His groundbreaking, portentously titled books, including WWI epic A Farewell to Arms and the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Old Man and The Sea, defined a new, disarmingly spare literary style for the so-called “lost generation” of the interwar years, doing away completely with the florid novelese of the 19th century in favour of stark, clipped sentences and close-to-the-bone realism. Of course, his contributions to literature have been duly recognised, as well as his enthusiasm for drinking – the first by his 1954 Nobel prize for literature and the second by the Bar Hemingway at the Ritz in Paris. But what is not-so-common knowledge is how Mr Hemingway became so marvellously brilliant in the first place – by stitching up his friends.

This is the story told by the rather wonderfully titled new book Everybody Behaves Badly, written by Vanity Fair and Wall Street Journal contributor Ms Lesley MM Blume. Chronicling the genesis of Mr Hemingway’s breakthrough debut novel, The Sun Also Rises (which turns 90 this year), it dives into his squalid, booze-soaked early days in Paris, where he moved with his first wife Hadley in 1921. With a sense of wry inevitability, it investigates the blossoming and demise of Mr Hemingway’s personal relationships with modernist greats such as Mr Ezra Pound and Ms Gertrude Stein, as well as the feckless Parisian socialites, including moneyed Guggenheim descendant Mr Harold Loeb and sozzled aristocrat Lady Duff Twysden, who would accompany him on a fateful 1925 trip to Pamplona and then be brutally lampooned in semi-fictional form in The Sun Also Rises.

All-in-all, it’s a fascinating portrait of an unpredictable and sometimes rather infuriating character, who was nonetheless somewhat worshipped by almost everyone he met. “He was at once noble and petulant; deeply ambitious yet strangely humble at times,” says Ms Blume of her subject. “He was charming and could be wildly generous, yet he could also be spiteful and even hateful, especially to those closest to him. He found ways to punish practically everyone who ever helped him.”

For anyone interested in the complex character of genius, therefore, Everybody Behaves Badly comes as recommended reading. But in the meantime, as a taster, we thought we’d pick out a few reasons why being part of Mr Hemingway’s circle could be somewhat trying.

HE INTRODUCED HIMSELF BY PUNCHING YOU

01.

One of the things that was singular about Mr Hemingway was his not-so-writerly sportiness and masculinity. Ms Blume notes how his early mentor Mr Sherwood Anderson described him as a “magnificent, broad-shouldered man” in 1921, just before he left for Paris. Unfortunately, a side-effect of this undoubtedly self-cultivated image was that one of the first things he did upon meeting a new acquaintance was challenge them to a boxing match. Though, says Ms Blume, “he made a poignant first impression upon [Ford Madox] Ford by shadowboxing his way through their first encounter”, when it came to his early friendship with Mr Harold Loeb (who would be painted, unflatteringly as the character Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises), he went the whole hog, despite the fact he “outweighed him by forty pounds”. “Luckily,” Ms Blume elaborates, “Loeb quickly learned that Hemingway telegraphed his punches by ‘a jiggling of the pupil’ – a discovery that gave Loeb a shot at survival.”

Mr Harold Loeb, Pamplona fiesta, 1925. Originally featured in The Way It Was by Mr Harold Loeb

HE WOULDN'T STOP TALKING ABOUT BULLFIGHTING

02.

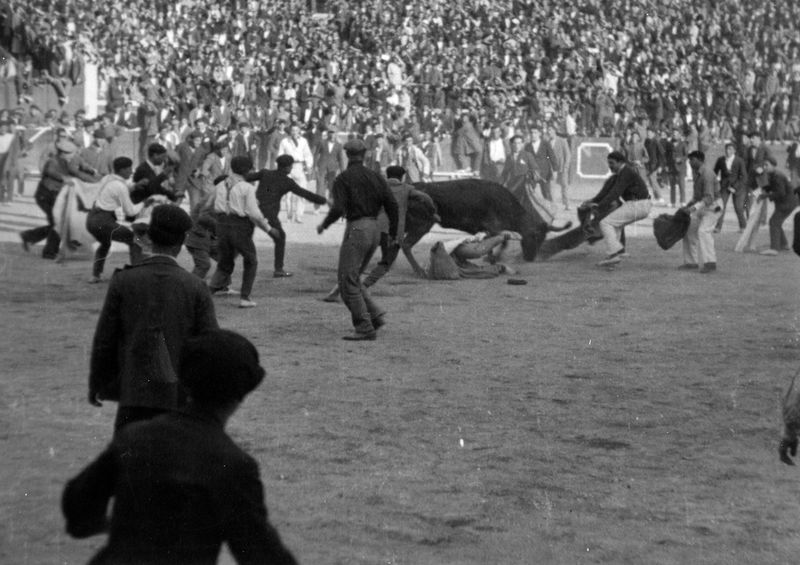

Besides writing (and drinking), bullfighting was one of Mr Hemingway’s great and most consuming passions. During his annual trips to the fiesta in Pamplona, Spain, he would even leap into the bullring during “amateur hour” to test his own mettle, and would expect his friends to do so too. Though Mr Loeb managed to actually leap on a bull’s head on one trip to Pamplona, he would later fall foul of Hemingway by criticising the sport. “Loeb seemed to be adding to his list of offenses daily,” writes Ms Blume. “Being less than sympathetic about bullfighting was one of the surest ways to antagonize Hemingway.”

Mr Hemingway and entourage at a café, during the San Fermin festival in Pamplona, July 1925. Photograph by Ernest Hemingway Collection, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

HE LIKED MAKING FUN OF PEOPLE

03.

Mr Hemingway was good at making friends, but he was also good at ridiculing them, in a very public way. The Sun Also Rises is a prime example of this – not only does it contain thinly veiled takedowns of his cohorts on his 1925 Pamplona trip – including the ever-suffering Mr Loeb, who would be haunted the rest of his life by the characterisation – it takes a swipe at Mr Ford Madox Ford (who is in there as “Braddocks”) and the rest of the Paris set of the 1920s. Prior to the publication of that novel, he wrote The Torrents of Spring, conceived as a parody of Mr Sherwood Anderson, the man who had introduced Hemingway to the Paris literary scene in the first place. Ms Blume also relates an incident in which he read out a cruel poem about New York critic Ms Dorothy Parker – un unwavering supporter of Hemingway’s work, in the company of satirist Mr Donald Stewart. According to Ms Blume, “the poem shocked Don Stewart, who later called it ‘viciously unfair and unfunny’. He could not discern a motive behind the attack, given that Hemingway was one of the few living artists who hadn’t suffered one of Parker’s poison-pen reviews.”

Everybody Behaves Badly (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) by Ms Lesley MM Blume is out now