THE JOURNAL

Photographs by Mr Reto Guntil and Mr Agi Simoes, courtesy of The Datai

At dawn, the butterflies come. There are 530 different species of butterfly in Langkawi, an archipelago of 99 islands off the northwest coast of Malaysia. In the UK, there are 65, 70 at a push. Here, I count five different kinds of butterfly alone in the first five minutes of my morning walk to the beach. Butterflies are obliging creatures. They get along with people. But I am still very much the guest of nature here, an interloper in trousers. This is confirmed when a belligerent macaque confronts me with a bread roll. “Ah,” says Mr Jonathan Chandrasakaran, a naturalist on Langkawi Island since 2015. “That was Joseph Stalin, the alpha male. He likes to go to the spa to pinch the tea.” I can’t complain: this 10-million-year-old forest is Joseph’s home. So, I take a right, down a different path. That is how things work here at The Datai. “If you see a python,” says the friendly security guard as I finally get near the beach, “just leave it and phone the reception.”

I’d arrived two days before on the 1.5-hour morning flight from Kuala Lumpur. The hotel driver, who picks up most guests, courteously points out a dusky-face langur monkey – “the friendly ones” – on a golf course as we drive and asks if I had been here before. I had, years before. “Big changes,” he says. He is right, too.

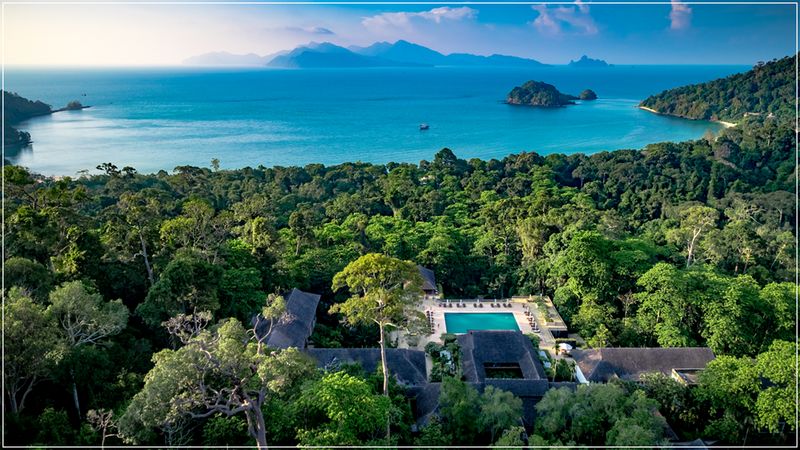

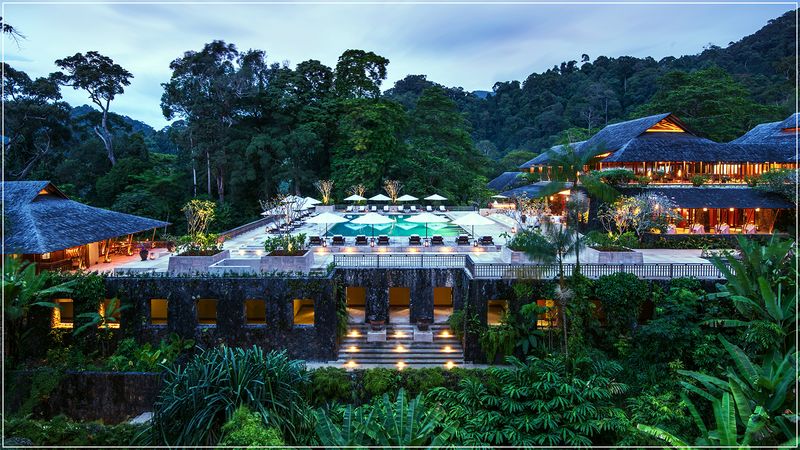

The 18-hectare Datai resort first opened in 1993. It was revolutionary, luxurious but eco-conscious, both in the jungle and on the beach. Set on a 40m-high ridge at the base of Machincang mountain, it was the first really top-flight hotel in the country, with a sensitively designed central block of rooms with individual villas dotted around it in the pre-historic forest.

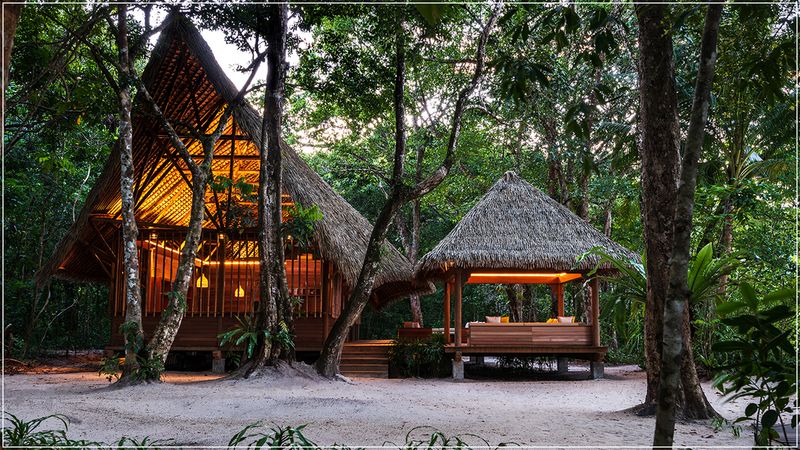

Designed by Mr Kerry Hill and Mr Didier Lefort to be a sort of five-star extension of the forest, it still loomed bright when I last visited, but perhaps needed a little facelift. “It was the right time to do a refurbishment,” says general manager, Mr Arnaud Girodon. “It had been more than two decades”. So, in 2017, it closed for 17 months while a top-to-bottom renovation took place. Mr Lefort came back to oversee and $60m was spent. More than 90 per cent of the furniture was changed. It took 20 mock-ups to perfect the new baths alone. A gym was built, in which you can row or run overlooking the Andaman Sea. The spa, a series of individual studios on stilts with patios down to a bubbling stream, was enlarged and beautified, and Mr Bastien Gonzalez, the Hollywood podiatrist, was brought in to design treatments. The four restaurants – The Dining Room, The Beach Club, The Gulai House and The Pavilion – all got a shot in the arm.

The most startling addition, though, is a beautiful beach-side nature centre and laboratory. This was built as a sort of bricks-and-mortar testimony to the resort’s famed naturalist and reigning divinity, Mr Irshad Mobarak, an investment banker turned botanist of 30 years standing whose great inspiration is Mr David Bellamy. Also because, well, there is such a lot to learn here. And it comes to you softly, almost by osmosis. On the first day, for instance, I find myself proudly possessed of the knowledge that the mantis shrimp is the fastest puncher in this bit of ocean, socking its prey at 80km per hour.

Flushed with this gem, I join an after-dark nature walk led by Mr Chandrasakaran again, the sprightly, pony-tailed nature centre manager, and six other guests. “Ah, very good,” Mr Chandrasakaran says with a smile. “No children.” Perhaps it would have been wiser to go on a nice beach walk instead? “First, I will take you to see a special animal I have spotted by the beach” he says. “Then I will show you something creepy by Villa 38. None of you are in Villa 38 are you?”

“If you see a python,” says the friendly security guard as I finally get near the beach, “just leave it and phone the reception”

In the 90 minutes we thread our way through the paths, we watch a flying lemur jet through the air, then meet a lesser mouse-deer – exactly as it sounds: both things comingled – on his evening constitutional. We see a flying squirrel dive bomb a tree. And then we get to Villa 38. In a wall nearby lives some miniature scorpions, their fluorescent shells glowing in the beam of his UV torch. “Don’t worry,” says Mr Chandrasakaran. “They are more scared of you.” They duly scuttle into the rocks. On the walk back to the beach house, we encounter a reticulated python high up a tree. “He isn’t interested in us.”

The Datai hotel is named for the bay it sits in. A U-shaped cove with a white sandy beach, its name translates roughly to “the free”, Thailand being “land of the free”. Its creation is the happy accident of geological drift. High cliffs surround the shallow, green-blue waters, and the forest pushes hard against the beach. It is a good place to sit, think, drink and recreate. The latter two abetted by the smiling, courteous staff.

After a morning spent staring happily at the sea, I board the Naga Pelangi, the hotel’s 65m hand-built junk schooner. A propitious wind pushes us north towards Koh Tarutao. We shelter under a lee before diving into the 27ºC waters and eat a picnic lunch under the benign gaze of the ship’s captain, Mr Christoph Swoboda, an old seadog to his fingertips, who merrily tells us stories of being boarded by pirates a few years previously. Mercifully not close to here, though.

Dinner that night is not in a restaurant, but literally on the beach, just two of us. This is one of the things organised by the tour operators, who get people to the Datai. Carrier, which specialises in the luxury, unusual experiences, has organised a table right by the water and hard by a grove of palm trees which fringe the beach. Operators such as Carrier have special relationships with the hotel and cajole and enjoin for their clients, getting the Datai to do extraordinary things. You name it, they’ll twist the arm of the hotel for you. Kayaking in the mangroves with a naturalist? Why not. Guided tours deep into the forest? We can do that.

At hotels like the Datai, when simply rising from a lounger yields some extraordinary experience, or encounter, it is hard to know how to deploy your time to best advantage, to know how to ferret out the best, the most interesting bits. And as most of us don’t go on holiday for a month, it is wise to have an operator like Carrier to gently guide and deftly organise, or you might miss the best bit. Plus the hotel seems to like the extra challenge.

Back at the beach, after dinner, full of lobster picked from the sea lapping at our feet, I walk back through the dark forest; the sounds of cicadas filling my ears, the air is still hot, I feel content. Grown an inch taller with the luxury of it all, buoyed up by the experience. And then a flying lemur bombs me from a tree and I belt off up the hill. He probably didn’t even see me. There is always an animal here to put you in your proper place.

I think I will go to see the butterflies again in the morning.