THE JOURNAL

Our story begins in 1980, although you could argue it began eight years earlier. The 1970s were a turbulent decade for the Swiss watch industry; quartz watches had been industrialised for the first time in 1969 and their ease of production wrought irreversible changes on the business of making mechanical watches. At the same moment, the leading watch brands faced rapidly changing tastes from their well-heeled customers – men who had been driving curvaceous E-Types or Ferrari 275s were now behind the wheels of wedge-shaped Lamborghinis – and needed something radical.

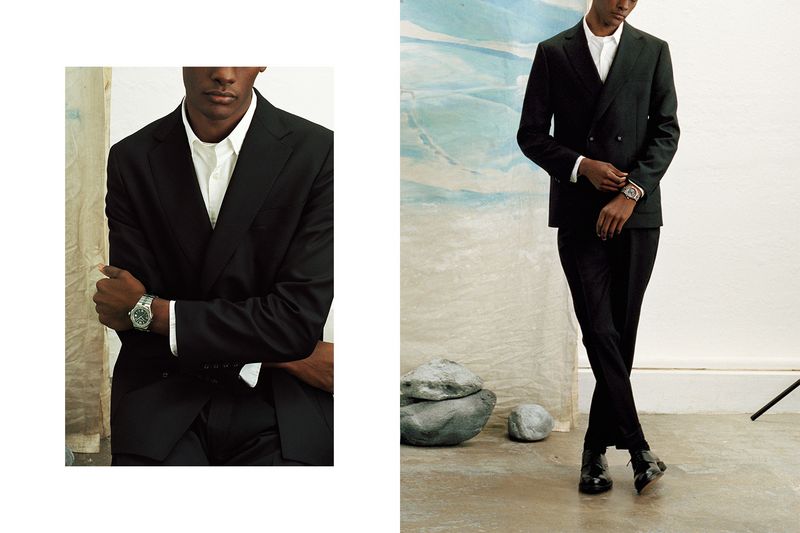

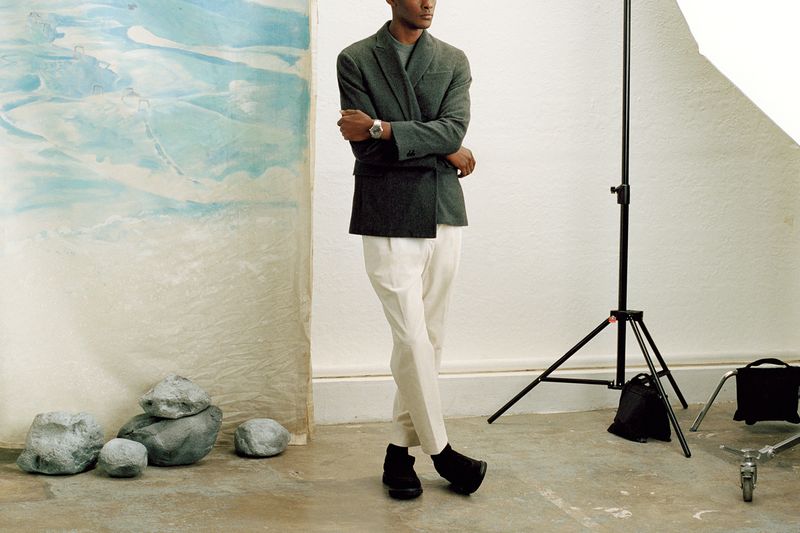

The industry delivered. Under pressure, it forged a generation of iconic watches, beginning with the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak in 1972 and swiftly followed by a half-dozen others. Now known as steel sports watches, they were defined by a few common characteristics, such as stainless steel cases that flowed directly into steel bracelets, and a louche fusion of high-end finishing techniques with casual, almost industrial, touchpoints: exposed screw-heads and angular edges.

Which brings us to 1980 and Mr Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, the then 22-year old son of Karl Scheufele III, president of Chopard, who proposed that the traditional maker of fine gold watches needed an answer to this trend; something that spoke to his generation. It would be called the St Moritz, in a nod to the Alpine hotspot popular with its high-rolling target market. His father took some convincing, but Mr Karl-Friedrich Scheufele got his way – Chopard launched its first ever steel watch, and joined a horological revolution.

Fast forward 40 years, and with the same 1970s icons dominating the watch marketplace, particularly evident in a vintage market showing few signs of slowdown, history was poised to repeat itself. Once again, Chopard was in the market for a new design, and once again, it would fall to the younger generation to provide it. Mr Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, whose very first project in the family business had been the St Moritz, has been co-president of the company since 2001, and under his careful stewardship and tireless ambition, it has become one of the most highly respected brands, with a state of the art manufacture in Fleurier. Yet it took his son, Karl-Fritz, to pull the same trick he himself had pulled on his father. In fact, all three generations had a part to play in the creation of the Alpine Eagle, as it was Karl senior who encouraged Karl-Fritz to press ahead with his proposal of reimagining the St Moritz for the 21st century.

The result is a watch with a familial resemblance to the St Moritz, yet very clearly with its own identity. The Alpine Eagle retains the standout features of its predecessor, namely the polished centre strip in its steel bracelet, and the pairs of exposed screw-heads at the cardinal points on the bezel, but in every area it represents one of the most elevated watches in its class by today’s standards.

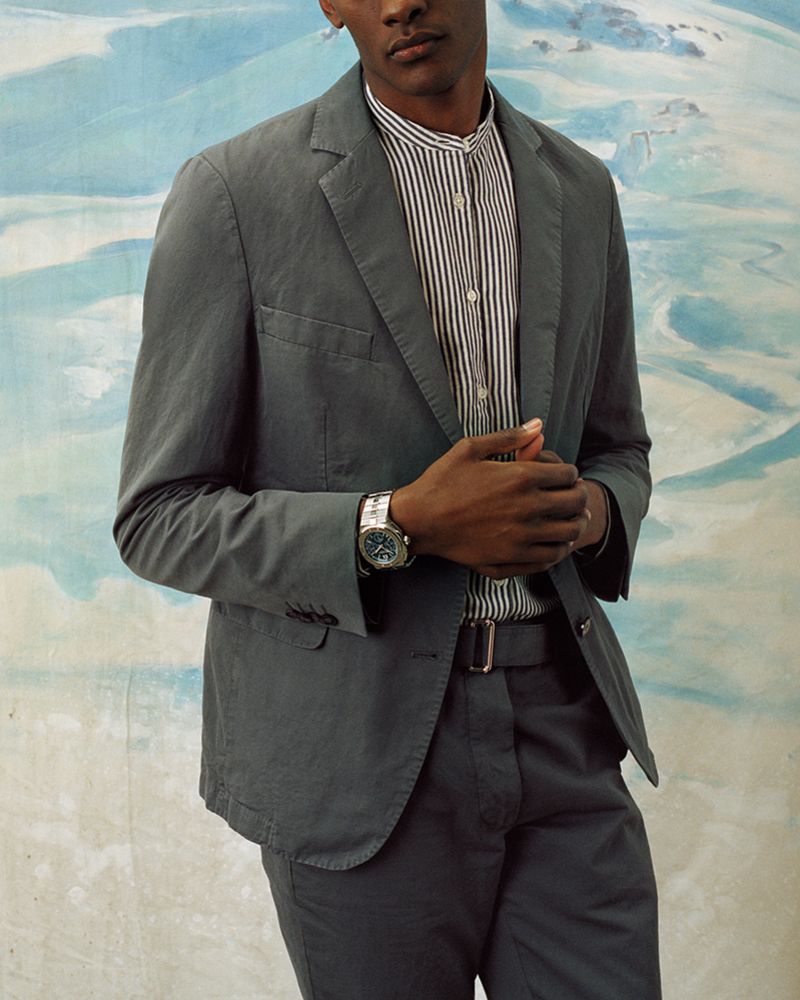

The 44mm chronograph models, the most recent additions to the Alpine Eagle range, use a movement borrowed from Chopard’s prestigious L.U.C models. It’s a true rival for any high-end automatic chronograph you can think of. It is one of very few with a jumping minute counter, for more precise timing; it holds four patents for various other technical improvements; and is the only watch of its type with a zero-reset for the running seconds (allowing you, should you desire, to easily set the time right down to the second). More everyday advantages include a 60-hour power reserve, a flyback function and 100m water resistance.

It’s worth lingering over some of the Alpine Eagle’s stylistic flourishes, too. Those screw heads in the bezel are all perfectly aligned at 90 degrees to the diameter – a tricky achievement explained when you turn the watch over and see the corresponding unaligned screw heads on the underside of the case; the ones on the top aren’t screwed in but held perfectly in place while the case is affixed from beneath.

Clever screwing is behind that eye-catching bracelet as well: each polished centre section is individually screwed in from the underside, in a system that also neatly holds the hinges between each link together, resulting in a more supple, flexible bracelet. Every flat surface of the case is finished with satin brushing, contrasted with finely polished bevels. In gold, it carries an expected lustre, but what’s truly impressive is that as a steel watch, the Alpine Eagle practically glows – and there’s a good reason for that.

Chopard has used a new and proprietary steel alloy that it names “Lucent Steel”. It’s twice-smelted to remove impurities and inclusions in the metal, with the effect of creating a metal that’s harder (223 on the Vickers scale compared with 150 for standard steel) and when polished, more reflective and brilliant than normal grades of steel used for watches. It’s comparable to surgical steel in its biocompatibility, and even better, it’s made from 70 per cent recycled metal.

Chopard has long made a point of improving the supply chains for its metals, having been a champion of fairmined and ethical gold (used throughout the Alpine Eagle collection) for several years. And its commitment to environmental initiatives doesn’t stop there: for two decades, Chopard has supported the Alp Action initiative aimed at preserving the natural habitats of the mountains. With the launch of the Alpine Eagle collection, it began a partnership with the Eagle Wings Foundation, a programme working to reintroduce the golden eagle to the Alps.