THE JOURNAL

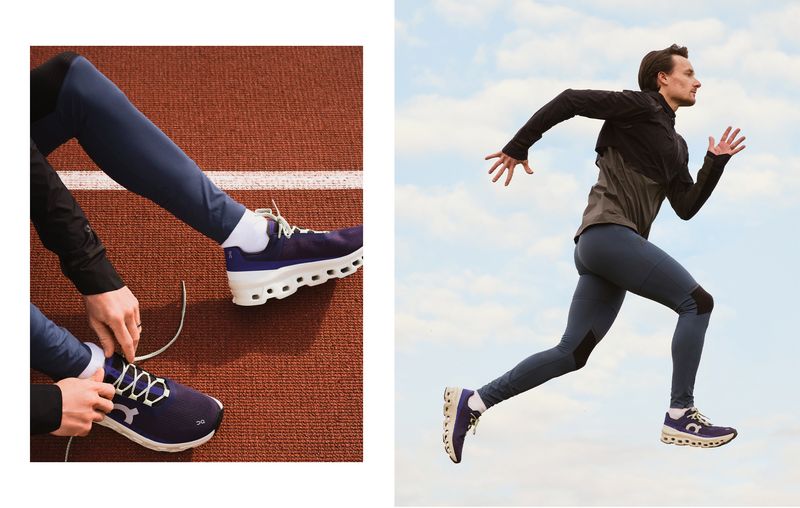

Mr Chris Thompson is not quite firing on all cylinders. The British distance-running legend is at Aldershot Military Stadium, the home of his athletics club, to test out the latest running shoe from ON, the super-cushioned – and wonderfully named – Cloudmonster. But something’s holding him back. (And no, it isn’t the shoe). He’s suffering from a mild case of what his chiropractor calls “dad-itis”, a condition whose symptoms include (but are not limited to) tiredness, aches and pains, and an occasionally overwhelming sense of parental responsibility. The cause? A one-year-old child, Theo, born just before Thompson’s 40th birthday, in the same breathless week that he qualified for Team GB’s Olympic marathon team with a personal-best time of two hours and 10 minutes.

We’ll repeat that: two hours and 10 minutes. At the age of 39. In the era of the sub two-hour marathon it can be easy to lose your sense of what’s normal, so it’s worth pointing out that by anyone’s standards, two hours and 10 minutes is fast. Ludicrously fast. To hold pace, you’d have to lap a 400-metre athletics track in 74 seconds. Then do it another 105 times. Or, if you’ve got a GPS watch to hand, it’s the equivalent of clocking a pace of 3.05min/km.

But to do it at a time in your life when received wisdom says you should be slowing down, not speeding up, is perhaps even more of an impressive feat. And that’s without mentioning the other factors. Just two months before the race, he’d smashed up his right hand in an accident with a removal van. Then there were his historic, race-inflicted injuries, the sort that any elite athlete expects but Thompson has been plagued by, most notably a persistent Achilles issue that had cast a shadow over a large part of his career, and from which he had only recently recovered.

Little wonder, then, that Thompson ranks his qualification for the Tokyo Olympics as perhaps his greatest athletic achievement. “I’ve been competing internationally for 26 years,” he says. “I’ve made teams umpteen times. I’ve been to the Olympics before, medalled at European Championships, held British records. But to do this, while dealing with so many other challenges? It felt special.”

Now, though, Thompson faces an even greater challenge – arguably his greatest yet. When he attends this July’s World Athletics Championships in Oregon he’ll be 41 years old, the most senior male competitor to represent Great Britain. But age isn’t the only challenge he has to overcome. Along with managing the prolonged recovery times and general wear and tear that come with getting older, he will also be contending with something else: the responsibilities of being a parent.

“Getting older as an athlete is one thing. Having a young child is another entirely. I’m sleeping less, I’ve got less time to train. I’m lifting around an object that is getting heavier every day”

“Getting older as an athlete is one thing,” he says. “Having a young child is another entirely. I’m sleeping less, I’ve got less time to train. I’m lifting around an object that is getting heavier every day and doing it all on my left side. Because of the way my body’s twisting, I’ll overcompensate on my right side when I run, and that can cause misalignments.” That’s behind the calf strain – sorry, the daditis – currently keeping him away from training at full intensity, but it’s not all he has on his plate. There are illnesses, too, which have been returning home with greater frequency since his child started nursery in January.

“I’m not looking for excuses or making up a sob story,” Thompson says. “Having a child was my choice. But at the same time, I’m up against other athletes who are not doing any of this and I’ve got to try and beat them. If I have a sleepless night because the baby’s brought a virus back from nursery and I can’t go on my regular 10-mile run, they’re not saying, ‘Well, Chris can’t train today, so I won’t either to make it fair’. That’s not how it works.”

So what is it that keeps him going, in spite of everything? Partly, it’s a stubbornness that finds satisfaction in overcoming adversity. “As a professional athlete, I’ve been in that situation where all you have to do is train,” he says. “But now I’m just an older guy with a family, trying to be the best I can be. I take a lot of pleasure from knowing that life is hard, and I can still do it.”

The other part is a deeply held faith in his own natural abilities, and in particular what he calls his “engine”. “Aerobically, I’ve never felt limited. I’ve always had big lungs,” he says. “When I first had them measured at Loughborough University, I was told that the only person they’d seen bigger was [four-time Olympic gold medal-winning rower] Matthew Pinsent.”

Because aerobic capacity typically peaks later than other forms of fitness, this engine is key to his longevity, too. The trick, he says, is figuring out how to reach and maintain peak form while scaling back his training. “It’s like a game of Kerplunk. You’re slowly taking more and more out while trying to keep all of your marbles.”

It quickly becomes apparent on spending much time in his presence that there are two sides to Thompson. One is a bloody-minded, never-say-die competitor for whom adversity is a source of motivation and age is just another obstacle. The other is an elite athlete with a deep, intuitive understanding of his own body and how to get the most out of it.

Success lies in the balance. “Elite performance is all about timing,” he says. “From where I’m standing right now, 16 weeks out from the World Athletics Championships, the thought of running 2:10 is daunting. But for an elite athlete it’s a tiny amount of time that you’re in that shape. But I know myself. And I know what it takes to get there.”

Will July in Oregon be his final championship event? Thompson can’t be sure. But as an ON athlete he’s confident that whatever happens, there will be a path forward. “We had a frank and open discussion after Tokyo,” he says, after a disappointing finish in sweltering conditions left his competitive future in doubt. “They asked me what I want, where I see my future, and how they can support that. Running can be fickle and transitioning out of the sport can be depressing, but I’m lucky that I don’t feel that way. I feel excited about my last race, whenever that might be.”