THE JOURNAL

To mark the launch of the latest Mr P. collection, the hands-on, Copenhagen-based creative takes a walk in our shoes.

It’s a cloudless day in Copenhagen. From his architectural studio in the old freeport, one of the last remaining industrial zones in a rapidly changing city, Mr Salem Charabi is perfectly positioned to watch as the urban sprawl encroaches ever further. “If you look out the window, you can see new residential developments approaching one dock at a time,” says the Egyptian-Danish architect, gesturing towards the city. “In a few years, this place will no longer be what it is right now.”

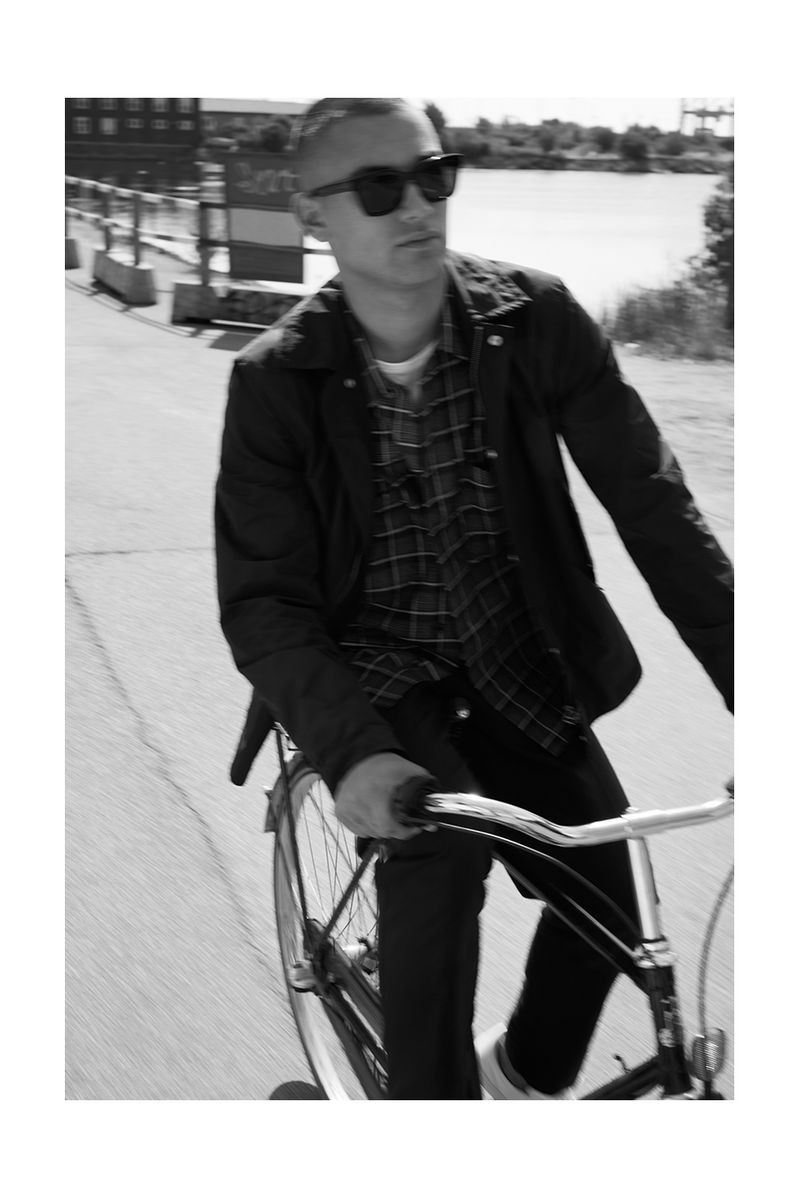

But cities are dynamic places, forever in flux. For his part, Mr Charabi is sanguine about the prospect of moving on when the time eventually comes. This studio – he refers to it as his “laboratory” – was once a factory producing diesel engines for boats. In a few short years, it’ll be swallowed up by the relentless onward march of 21st-century Copenhagen. “It’s a short-lived luxury,” he says. “I have to accept that this is just one stage of my life.” For now, he’s making the most of having his own private space a mere 10 minutes away from the centre of Copenhagen by bike – and all of this at just 26 years old.

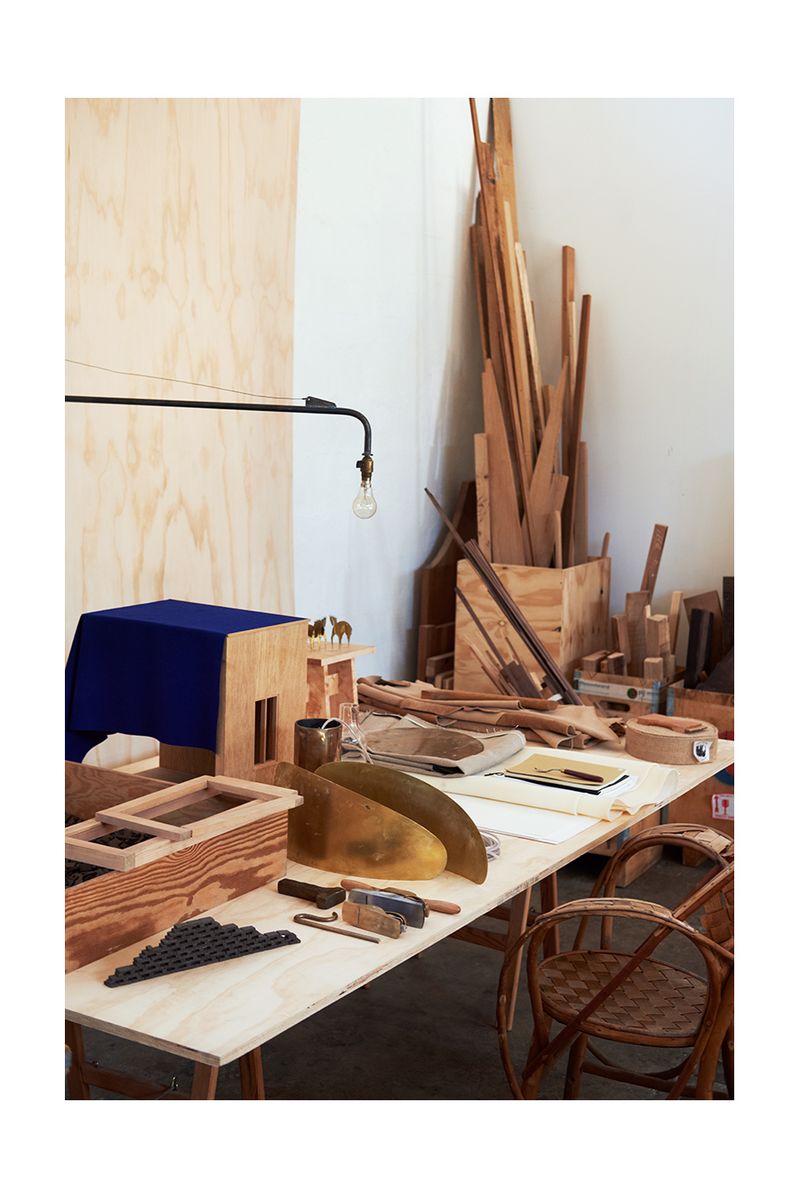

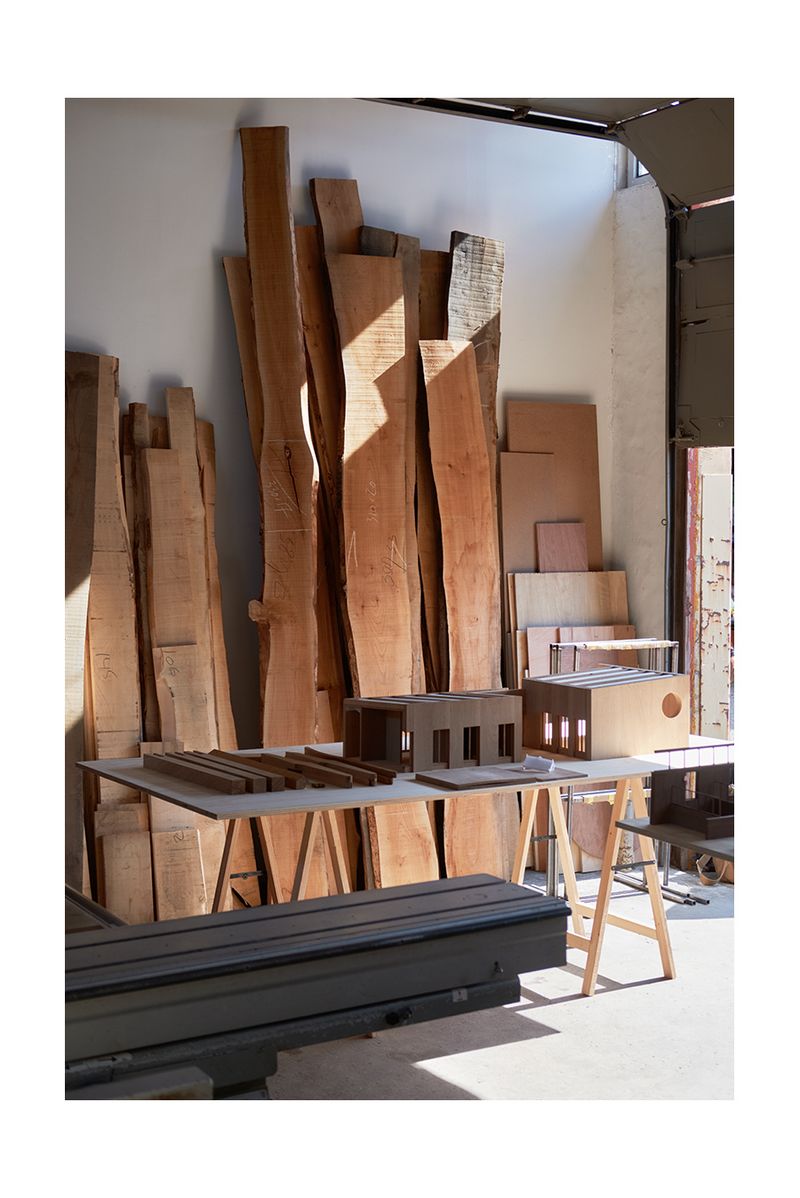

The space itself is airy, open-plan and large enough to design smaller projects on a 1:1 scale, which is the way that Mr Charabi prefers to work. “Normally, you make a set of architectural drawings and send them off to someone else, who handles production,” he explains. “For me, while there’s something undeniably magical about drawing, there’s a disconnection with the final product. I prefer to be able to see the results of what I’m doing straight away. Working on a 1:1 scale offers an intimacy with the materials and the techniques.”

A tour of the warehouse reveals the extent of his commitment to hands-on architecture. In one corner, standing next to a scale model of a stables, are three model horses made of slotted-together sheets of brass (a little like those wooden dinosaur models you tend to find in gift shops at natural history museums the world over) inspired by a sketch by Mr Henri Matisse, which Mr Charabi made after failing to find appropriately sized horses in a toy shop. In another are handmade wooden leg joints designed for an exquisite nubuck-leather day bed. “They take a few attempts to get right,” he says, frowning at a discarded prototype that looks flawless to the untrained eye.

An unconventional architect, Mr Charabi also has unconventional needs when it comes to clothing. And just as he sees his own work as a response to a set of practical conditions – a building’s intended use, say, or its geographical location – so he expects the clothes he wears to fulfil the requirements of his day-to-day life. “I don’t just sit down and start drawing,” he says. “The way I work dictates a different expression of my personal style.”

Mr Charabi’s respect for the relationship between form and function, which is as evident in his work as it is in the way he dresses, is the essence of good design. It’s something that we make every effort to practice ourselves at MR PORTER with our in-house label, Mr P., which enters its fifth season this week. To mark the occasion, we asked Mr Charabi to share his thoughts on practical style.

What are your main criteria for choosing clothes?

Because I live in Copenhagen and travel by bike, there is a climate to adapt to; because of the fact that I work in a workshop, there are a set of practical conditions that I have to respond to; and because I’m not always in my workshop, there are a range of different activities that I need to be prepared for. Rather than waking up in the morning and saying, “I want to wear blue today”, the way I dress is more about responding to these basic needs.

You must also be motivated by a desire to look good, surely?

I grew up with a father who taught me that it was my responsibility to present myself well, and I work in a field of visual design, so naturally I’m attracted to objects that are beautiful and well-made.

What about fabrics? Given the nature of your work, do you expect a certain resilience from your clothes?

Absolutely. As with everything I create in my workshop, I expect the clothes I buy to come with some kind of promise that they will develop over time and stand up to whatever the day might bring.

A common theme in architecture is “patina”. Is it important for you that things age well?

There’s something very satisfying about a brand-new object, but personally I think that anything that has an age and tells a story somehow has a more profound richness to it. This is the reason we’re so fascinated when we enter an old warehouse or walk the narrow streets of Copenhagen. There’s a sense of a life lived before you, as if the social interactions that happened in the past have manifested themselves physically in the surroundings.

This isn’t just limited to architecture, of course.

No, it applies to clothes as well. Of course there’s something extraordinarily satisfying about putting on a brand-new pair of sneakers, but there’s also a certain personality about a well-worn item. You see a pocket that has heavy use from the workshop, that has an extra polish or wear. And while this doesn’t rule out anything that’s new, it teaches you to only buy things that you intend to keep.