THE JOURNAL

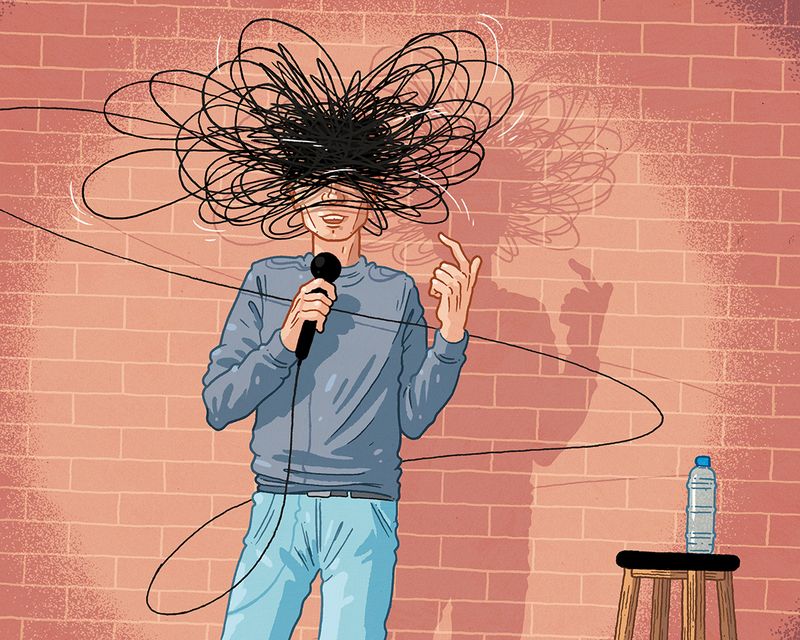

Illustration by Mr Jasper Rietman

To my continual delight and astonishment, being a comedian is my job. Over the years, the act of writing and performing comedy has given me immense joy. It has also, at times, made me thoroughly, excruciatingly miserable.

This isn’t to say that my personal style of comedy – I’m one half of a double act called Max & Ivan and we’ve created live shows, scripted podcasts, unscripted podcasts and sitcoms for Radio 4 and, most recently, ITV2 – is particularly dark or reliant on deeply personal revelations. It’s just that, well, making comedy can be hard. The long-time comedy critic Mr Bruce Dessau has a regular feature in which he asks comedians which of two categories they feel they fall into: golfers, who just get on with life, or self-harmers, who are tortured artists. The comedian Mr Joe Lycett’s answer, I feel, best sums up my relationship with comedy: “I am a self-harming golfer.”

To be clear, if you’ve ever thought about giving comedy a go, I highly, highly recommend you try it. It’s fun! It’s challenging! It’s an adrenaline rush! And it can, without a shadow of a doubt, be good for you. “Stand-up comedy’s so amazing,” says the comedian Ms Angie Belcher. “It’s not just about entertaining people. It’s a political act and it can change people’s lives.”

Belcher is also a facilitator who organises workshops, including Aftermirth, for new parents, and Eldermirth, for people in care homes, which bring stand-up to groups who don’t ordinarily get the chance to experience it for themselves. Her newest project, Comedy On Referral, is a stand-up course for men at risk of suicide and has just won NHS funding. “The feedback I’ve had from the courses has been amazing,” says Belcher. “People saying things like, ‘This course has made me want to push for a better life,’ and – simple, but really important – ‘This course has made me feel better.’”

I’m not surprised. Comedy has, without a doubt, the power to explore personal and painful themes and, by doing so, take ownership of them. As the mighty Mr Robin Williams reportedly said, “I think the saddest people always try their hardest to make people happy because they know what it’s like to feel absolutely worthless and they don’t want anyone else to feel like that.” The sheer act of turning something into a joke is also the act of processing an experience, of gaining perspective on it. It can, and should, be a joyful, soul-nourishing act.

“Stand-up comedy’s so amazing. It’s not just about entertaining people. It’s a political act and it can change people’s lives”

“Comedy, for me, has proved to be the best kind of outlet for my mental health problems,” says Mr Richard Gadd, the award-winning comedian and actor whose extraordinary one-man shows, Monkey See Monkey Do and Baby Reindeer, have unflinchingly explored his personal traumas. “To put my social anxieties, depressions, traumas and illnesses out there and have an audience laugh, clap or generally meet them with positivity, it made those problems seem less weighty inside my head.”

Mr Jack Rooke, too, is a superb comic who has explored mental health via the medium of comedy. “A lot of depressed people I know are also very funny, life-and-soul-of-the-party types,” he says. “I think comedy allows people to fully own their own experiences in a way that makes it fun for audiences to relate to. I’d rather watch a stand-up chat about mental illness than a very serious play. I feel like you need the joy that comedy brings. It’s kind of part of the remedy.”

Rooke has taken care to ensure that joy is present in his Channel 4 sitcom Big Boys. “What I’ve tried to do is make sure we’re discussing mental health in a way that can still be joyful and where characters going through depression can still be funny and charming and not too one-note miserable,” he says. “No sad ukulele music over the depressed character please! We’ll have some Hot Chip instead.”

Rooke’s right. Dealing with depression needn’t be depressing to watch. For empirical proof, watch Mr James Acaster’s Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999, which tackles therapy, professional disappointments and heartbreak and is, to my mind, the finest and funniest piece of stand-up comedy ever created.

In 2010, Mr Bo Burnham, then a 19-year-old YouTube star riding the crest of a viral wave for his witty, smutty songs, came to the Edinburgh Fringe and blew everyone away with his live show, Words, Words, Words, which won an Edinburgh Comedy Award. When asked why he’d opted to come to Scotland to perform night after night in a small sweaty theatre – something he had no need to do – he said, “Performing is my favourite way to be.” I know exactly what he means.

“My anxieties towards comedy have manifested in the interplay between it being both my passion and my job. I spend as much time focused on how to monetise my work as I do experiencing the pure joy of writing or, when it goes well, performing”

I painstakingly, delicately, craft live shows over months – periods of trial and error that are often excruciating, for both me and the audience – before eventually fine-tuning an hour of comedy that feels as close to flawless, to complete, as I can make it. Eventually, when it clicks, the experience of existing within the world you’ve created is addictive and exhilarating. The show is an active, living thing, a crackling, continuous exchange between the performer and the audience, in which the unexpected can happen, but you always know where you’re going. It’s a rush, but the process of getting there is illogical, often painful, and there are no shortcuts. Not even Mr Jerry Seinfeld is exempt from this. Watch the 2002 documentary Comedian and you’ll see him building a show from scratch, with all the stresses and pitfalls and creative dead ends that entails.

The closeness one has to one’s own work can result in an unhealthy relationship to it, too. When on tour with a subsequent show, Burnham experienced 12 panic attacks, which marked the start of him moving away from live performance. Acaster, too, has discussed no longer enjoying stand-up and contemplated quitting.

As for me, my anxieties towards comedy have manifested in the interplay between it being both my passion and my job. I spend as much time focused on how to monetise my work as I do experiencing the pure joy of writing or, when it goes well, performing. When the pandemic hit and the world fell apart, so, too, did my ability to pay my bills and so, too, did my identity. It was a time of global anxiety, of course, and the all-encompassing sense of uncertainty and worry I experienced, both as a performer and a person, was expressed most eloquently by, who else, Burnham. His Netflix special Inside, written and filmed solo during lockdown, in his house in front of an audience of nobody, masterfully touches upon almost every anxiety I experienced during that time: self-doubt, myopia, worries about ageing, loneliness and the futility of humour. Burnham’s special is so spectacularly good that it cooked up a whole new type of anxiety – how can I possibly ever use comedy to explore my own inner life in ways that Bo Burnham hasn’t already done far more brilliantly?

I’m getting ahead of myself. To reiterate, as an experience, or a hobby, performing stand-up is a radical, transformative act – cathartic, empowering, thrilling. And as a job? Well, it can still, without a shadow of a doubt, be all of those things. But, as Burnham says in his third show, Make Happy, when he sits with the house lights up and addresses the crowd directly, “If you can live your life without an audience, you should do it.”