THE JOURNAL

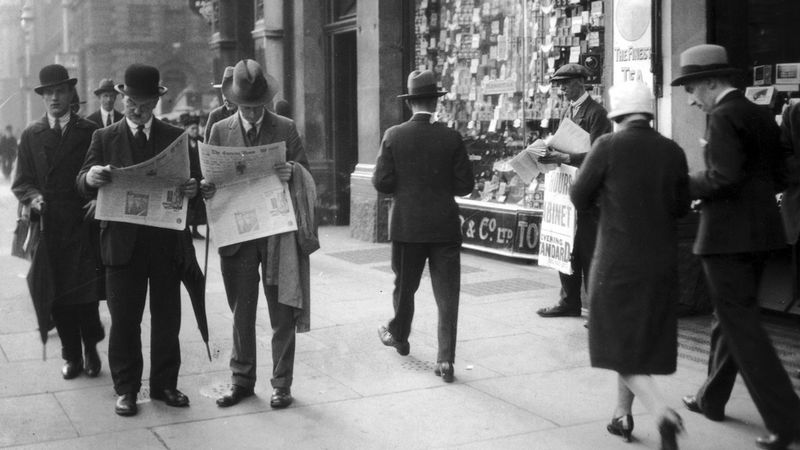

Two businessmen reading the financial sections of their newspapers, London, 1925. Photograph by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Neuroscientist Mr Daniel Levetin shares tips from his new book on how to decipher fact from fiction in the information age.

On Wednesday 11 January 2017, Mr Donald Trump – you know, the President of the United States of America – pointed at a reporter from CNN (one of the country’s most respected broadcasters) with the damning accusation: “You are fake news”. He was referring to a dossier, reported upon by CNN and released in full by Buzzfeed, that contained many claims about Mr Trump’s relationship with Russia. There was no real evidence to support these claims, hence the indignant response. Later, on Sunday 22 January, White House aide Ms Kellyanne Conway appeared on NBC’s Meet The Press and stated that the White House press secretary Mr Sean Spicer had described audience numbers at Mr Trump’s inauguration with “alternative facts”. NBC anchor Mr Chuck Todd said, “look, alternative facts are not facts. They’re falsehoods”.

This is where we are right now. Whether we’re calling it fake news, alternative facts, misrepresentations or plain old fibs, we’ve suddenly become aware that not everything we read and see out there, on TV, on the internet, in print, is strictly speaking, 100 per cent… true. Of course, the concept of “fake news” is one that was talked about following the 2016 presidential election – in which credible-looking but ultimately untrue stories about both candidates were circulated by a variety of outlets on social media – but this is not exactly a new problem. In fact, governments, advertisers, journalists and independent voices on the internet have long been twisting the facts to get their messages across, not always in an entirely honest fashion. The difference now, according to neuroscientist Mr Daniel Levitin, is that there’s just so much confusing information out there. “In the current information age, pseudo-facts masquerade as facts, misinformation can be indistinguishable from true information, and numbers are often at the heart of any important claim or decision,” Mr Levitin says. “Bad statistics are everywhere.”

It’s an apt time, then for the re-publication of Mr Levitin’s book A Field Guide To Lies And Statistics, an engrossing volume of advice about how to think critically and scientifically about the things we are told by governments, the media, and even our friends. Covering everything from graphs and diagrams (and how to cheat with them) to probability and logic, to when and how to evaluate the worth of expert opinions, it functions as a helpful toolkit for dissecting news stories and claims, with the aim of finding that ever-elusive quality: the truth. Below, we’ve collected just a few of Mr Levitin’s tips for seeing the facts clearly – if you want a complete dose of his wisdom though we recommend ordering a copy of the whole book, which is out now from Viking.

Graphs are not always what they seem

01.

Mr Levitin spends the opening section of his book demonstrating how data can be represented visually, and how those visualisations can be misleading. One way to make a chart go your way, says Mr Levitin, is to fiddle with scale on the axes, so that a small change looks like a giant leap. Another is to employ two different Y axes, so that you are comparing two sets of results at a different scale. Our favourite example of a dodgy graph, though, has to come from Apple’s CEO Mr Tim Cook. During a presentation on iPhone sales in 2013, he presented a graph of “cumulative sales”, which showed the number of iPhones sold to date (including all previous years) across a timeline. Obviously, this kind of graph can only go up, which meant that it looked like iPhone sales were rising. In fact, they had slowed – but you wouldn’t see that from a quick glance. “Just because someone quotes you a statistic or shows you a graph, it doesn’t mean it’s relevant to the point they’re trying to make,” writes Mr Levitin. “It’s the job of us all to make sure we get the information that matters, and to ignore the information that doesn’t.”

Statistics need context

02.

When presented with numbers, people often accept them unquestioningly. But not all numbers are equal, according to Mr Levitin. “Remember… people gather statistics,” he writes. “People choose what to count, how to go about counting.” As one example of how statistics can mislead, he refers to a classic Colgate ad. “You’ve probably heard some variant of the claim that ‘four out of five dentists recommend Colgate toothpaste’”. That’s true. What the ad agency behind these decades-old ads wants you to think is that the dentists prefer Colgate above and beyond the other brands. But that’s not true. The Advertising Standards Authority in the United Kingdom investigated this claim and ruled it an unfair practice because the survey that was conducted allowed dentists to recommend more than one toothpaste. In fact, Colgate’s biggest competitor was named nearly as often as Colgate (a detail you won’t see in Colgate’s campaigns).

Probability can be conditional

03.

In his chapter about probabilities, Mr Levitin is keen to point out the idea of “conditional probabilities”. As an example, he asks: “What is the probability you have pneumonia? Not very high. But if we know more about you and your particular case, the probability may be higher or lower.” Later, he illustrates how this kind of probability can be used to mislead, by discussing the example of a manufacturer of security cameras that claims that “90 per cent of home robberies are solved with video supplied by the homeowner”. This gives the impression that if you were robbed, having a security camera would give you a 90 per cent chance of your case being solved. But that is not true. There is a conditional probability here – the 90 per cent only applies to the fraction of robberies actually solved, and not all robberies commited. Which in effect tells us nothing, says Mr Levitin. “All you know is that if a robbery is solved, there is a 90 per cent chance the police were aided by a home video,” he writes. “If you’re thinking that we have enough information to answer the question you’re really interested in (what is the chance that the police will be able to solve a burglary at my house if I buy a home-security system versus if I don’t), you’re wrong.”

A Field Guide To Lies And Statistics (Viking) by Mr Daniel Levitin is available now