THE JOURNAL

Mr Laurent Fignon, in the Alps on the climb of the Col de la Madeleine, 2001. Photograph by Cor Vos

With the first stage of the 2016 Tour de France beginning soon, we look back at the men who turned riding a bike into an art form.

What makes a stylish cyclist? First, it must be understood that style on a bicycle is very different from style off a bicycle. When riding, a good style is typified by a relaxed expression, an elegant position upon the machine, and a smooth, even cadence, so it appears the athlete is dancing on the pedals, not stamping on them in the manner of an angry elephant. Essential to good style is what the French call souplesse: literally suppleness, but more accurately the ability to conceal great power behind practised fluidity. Of course, there are sartorial rules, too – on length of sock, on mutual compatibility of shorts and jersey, of angle of cap brim. Some men, however, had enough style to see them to the finish line and way beyond. Here are five of the suavest pros to ever turn a chainring.

Mr David Millar

Mr David Millar during the Tour de France, 2002. Photograph by Lars Ronbog/FrontzoneSport via Getty Images

For the most part, the modern peloton is filled with the sort of cloistered anti-aesthete that knows only the world of professional sport. Usually clad in the largely unflattering Day-Glo of their team colours, they don’t pay much attention to their leisure-time outfits. Mr David Millar, on the other hand, has the distinction of looking as good off the bike as on it. In competition, he excelled at time trials, having the ability to lock into a perfectly tucked aerodynamic shape and hold it till the end. He retired in 2014 after a career that included becoming the first ever British rider to hold the leader’s jersey in all three Grand Tours; his sartorial achievements include the launch of his own Chpt./// line of understated performance cycling gear, which has a combination of style and practicality and nothing in common with the garishly slogan-covered apparel it is designed to replace. You can wear it yourself to attempt to channel some of his sophistication.

Mr Laurent Fignon

Mr Laurent Fignon, in the Alps on the climb of the Col de la Madeleine, 2001. Photograph by Cor Vos

It’s a sporting travesty that this studious Frenchman has become posthumously famous for his part in the 1989 Tour de France, when, despite leading until the last stage, he surrendered the overall classification to Mr Greg LeMond by a heartbreakingly small margin. Through his professional days, Mr Fignon did something that was never done before, though, and has never been done since: he wore a ponytail, a patterned headband and spectacles on a bicycle, and wore them well. This was the 1980s, so he was allowed to. The antithesis of the anti-intellectual sportsman, Mr Fignon brought steel and style to his sport, as well as a razor-sharp mind. “I remember you,” a cycling fan once said to him. “You’re the guy who lost the Tour de France by eight seconds.” Mr Fignon replied: “No, monsieur, I’m the guy who won it twice.” Pure class.

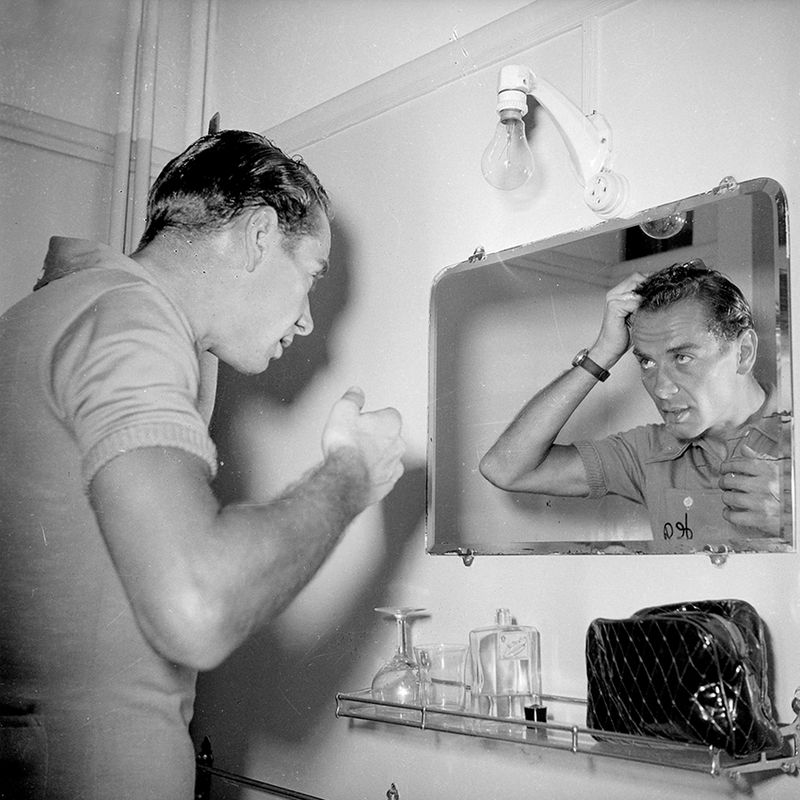

Mr Hugo Koblet

Mr Hugo Koblet off-duty during the Tour de France, 1951. Photograph by Offside/L'Equipe

He had the finely sculpted features of a Mr James Dean, and he died a similarly tragic death behind the wheel of a fast car. Before that, his life was one of domineering victory and public adulation, with a few dalliances with models thrown in, too. Mr Hugo Koblet famously wore a watch (Swiss and expensive, like him) and carried a comb and a small bottle of cologne during races, so that when he crossed the line (inevitably first), he’d be able to look like the star he undoubtedly was. Somehow, the climber pulled off such narcissism and gained the nickname the “Pédaleur de Charme” – he remains the epitome of riding refinement.

Mr Jacques Anquetil

Mr Jacques Anquetil in Italy before the 1960 Giro D’Italia. Photograph by Offside/L'Equipe

What is it about professional cycling, especially during its golden age in the 20th century, that gives it such opportunity for displays of panache? Is it the inherent Continental glamour; is it the tanned and lithe bodies; is it the insouciance of a rakishly cocked casquette? Whatever it is, Mr Jacques Anquetil had it in abundance. The preeminent tour rider of his day had perfectly coiffed hair, piercing blue eyes and a nice line in tailored clothing that made him stand out from his often rough-and-ready fellows in the peloton. Mr Anquetil was a serial seducer of women, a driver of sports cars, a drinker of fine champagne and a smoker of post-win cigars: Frenchness personified and impossible to emulate.

Mr Fausto Coppi

Mr Fausto Coppi during the Tour de France, 1949. Photograph by Offside/L'Equipe

It’s a rule of cycling: never say his name without including “The Great” as a prefix. Otherwise, Il Campionissimo, the Champion of Champions, is enough. No one won like Mr Fausto Coppi. Over a career torn in half by WWII, the Italian topped podiums all over Europe as a matter of routine. His ignominious death aged 40 in 1960 preserved him forever in atmospheric mid-century monochrome; whether signing autographs in his favoured Persol shades, gliding solo up an Alpine pass or stepping out with an army officer’s wife in an affair that scandalised his country, he did it with effortless grace. He possessed the easy glamour of an off-duty movie star in a Rimini beach resort: wide suits, sharp lapels and slicked-back sophistication.