THE JOURNAL

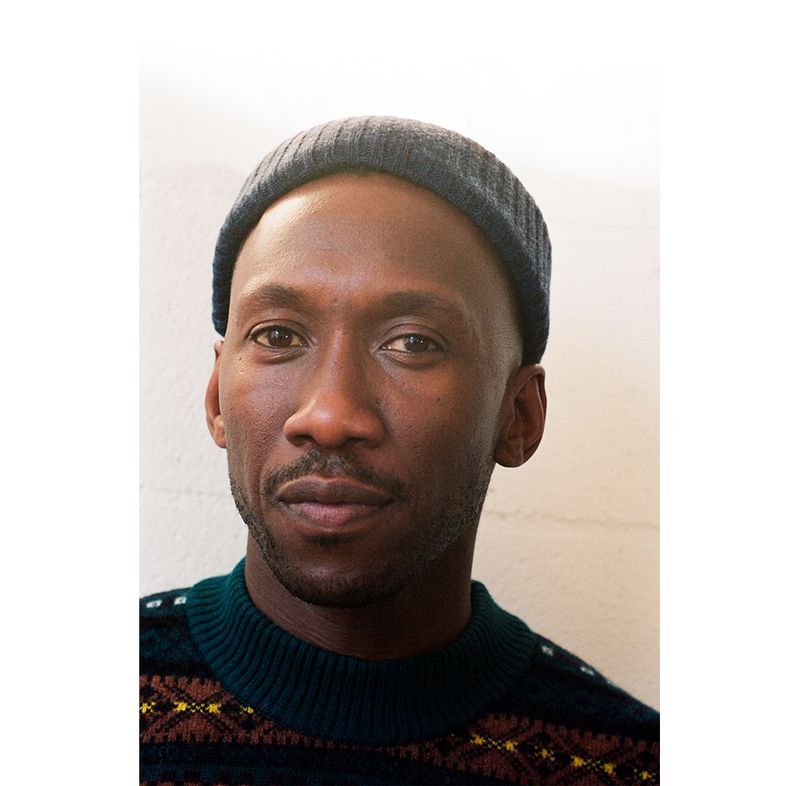

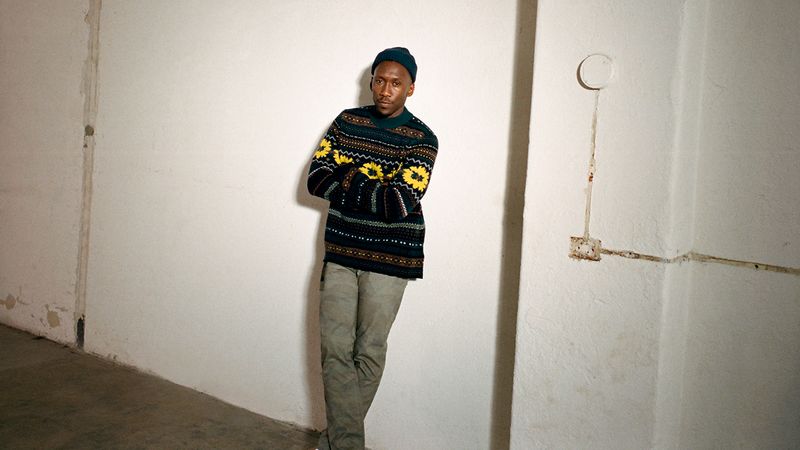

The <i>Moonlight</i> and <i>Green Book</i> star reflects on a bumper year.

A new baby. A new house. A new Oscar. The past couple of years have been a bit of a whirlwind for Mr Mahershala Ali.

“Usually it’s just one of those things,” the 44-year-old actor says. “But we had a few of them at once so we’ve been in this constant state of discombobulation. And I think my wife and I are both fighting for steadiness, calm, but at the same time listening to the demands of the circumstances, and not wanting to take anything for granted.”

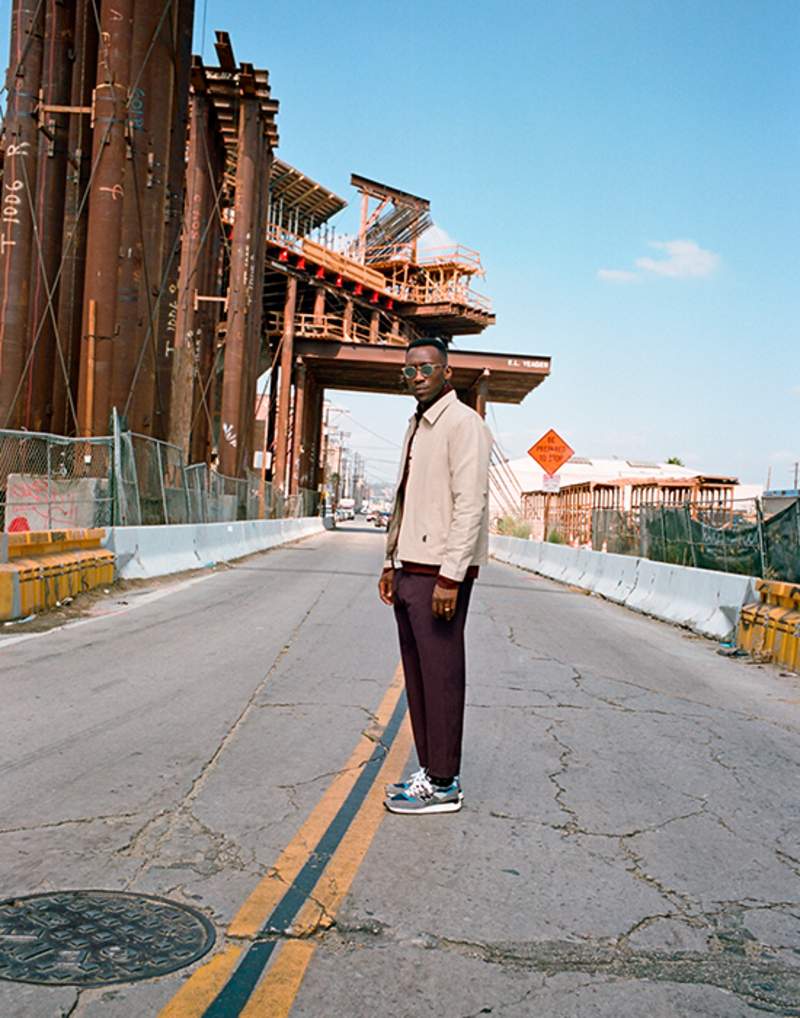

We’re sitting on the terrace of LA’s Sunset Tower. It is a late breakfast hour and Mr Ali is the very picture of calm in an immaculate Nehru-collar button up, long, kimono-style denim jacket and plimsolls. The last time we met was a year and a half ago, before his life went supernova. This was in late January of 2017, when his performance as the mentor figure Juan in Moonlight was just beginning to catch fire in the popular consciousness, and garner serious award season recognition. After nearly two decades of steady work, in film and on television, Mr Ali was, suddenly, being noticed (or, as he joked, “I worked 16 years to become an overnight sensation”). More than that, he was being stopped in the street. People would approach him while he was out with his wife, at dinner, and share with him their stories, stories unearthed by his performance as an avuncular drug dealer who takes care of a struggling young boy in Miami.

“I realise that, even after a performance is over,” he told me then, “you still have to service it. I’ll be in a coffee shop and someone will come up to me, and just open a vein, telling me how this struck a nerve for them, what their experience was. And I really try to be present for that. I’m really thankful for that.”

That attentiveness, or responsiveness, has won Mr Ali a legion of fans, both within Hollywood and without. It has set him up for parts in prestige awards fare, such as Green Book with Mr Viggo Mortensen. But also for blockbuster stardom, with the likes of Messrs James Cameron and Robert Rodriguez’s Alita: Battle Angel, which will arrive early next year, and for the starring role in the upcoming third season of HBO’s True Detective series. It’s also propelled him into an enviable position within the industry: of having to, at times, say no.

“I think I’ve always put a lot of pressure on myself,” he says now. “I’m naturally really particular and specific. So, as I’ve had more opportunity, I think, if anything, it’s given me more freedom to let go of what doesn't really speak to me and take advantage of the opportunity to say yes to the projects that resonate.”

Mr Ali was born and raised in Oakland, California. Both his mother, Ms Willicia Rucker, and maternal grandfather were ordained ministers. His father, Mr Phillip Gilmore, was a prolific Broadway performer, and Mr Ali vividly remembers his visits to Manhattan as a kid, running around backstage, awash in the florid costumes and the personalities of the 1980s theatre community. Back home in Cali, in the jock-y corridors of his high school, and then at St. Mary’s College, which he attended on a basketball scholarship, Mr Ali projected a more “buttoned-up” masculinity. Still he found room for expression in poetry, which may have been the gateway to his career, he says now.

“I think I got into acting by performing my poetry,” he says, “I wasn't conscious of it at the time. But I was taking things that were deeply personal – things that I was wrestling with or things that I had observed – and putting them in the context of fiction, through performance or monologues, for the sake of communicating larger ideas. So I always related to writing from the standpoint of it being metabolized and shared, and sort of performed.”

In Green Book, his latest film, Mr Ali plays elegant Jamaican concert pianist Mr Don Shirley, who hires his rough and rude counterpart (Mr Mortensen) to chauffeur him through the American South on a tour in the 1960s. Like the actor himself, Mr Shirley is particular in his taste for tailored suits and accessories. But his speech and manner is polished almost to the point of delicacy – a thin shield, worn to protect his pain within.

The film is full of odd-couple humour, and takes particular delight in toying with the characters’ suppositions about the identities and predilections ascribed to them by their lots in life, their race, religion, creed, profession. (The Green Book of the title was a kind of Baedeker guide for African-Americans navigating the south at the time.) It’s a culturally sensitive film and won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto Film Festival and Messrs Ali and Mortensen are fantastic.

Beyond the work, Mr Ali hasn’t shirked opportunities to do something worthwhile with his position. When accepting the 2017 Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Supporting Actor, for example, he gave an impassioned speech on the value of inclusivity, of seeing one another by looking past our differences. “My mother’s an ordained minister,” he said. “I’m a Muslim. She didn’t do backflips when I called her to tell her I converted 17 years ago. But I tell you now, we put things to the side, I’m able to see her, she’s able to see me, we love each other, the love has grown. That stuff is minutiae. It’s not that important.”

At a time when speech itself matters, Mr Ali’s words were incredible, so thoughtfully precise in his diction – whether on stage or in person. Mr Ali clearly cares a great deal about expressing himself, about expressing himself exactly as he means to – and that care he takes, the joy he takes in speaking about big things, about delicate, nuanced, or very personal things is instructive.

Mr Ali first met his now wife, the artist Ms Amatus Sami-Karim, when they were both at NYU during the conscious era of the 1990s (it was during this time that Mr Ali converted to Islam). He gave her a love note. Much later, Mr Ali and Ms Karim reconnected after losing touch, when he called her out of the blue, and they talked and talked and talked on the phone (they were married in 2013). Words again.

I ask him where this love of words comes from. “When I was a kid, my mom would cut me off when I was trying to explain why I did something that was perceived to be wrong,” he says. “I would start explaining myself and get a little specific and at a certain point she was like, ‘You’re not going to lawyer your way out of this.’ And I was like, ‘I’m just trying to explain why I made the choice that I made.’”

Aside from his mother, his grandfather was a great influence. “I spent a lot of time with my grandfather, my dad’s father – I lived with them for a good portion of my life. He was a local chapter president of the NAACP in Alameda and then later in Hayward [in California]. And every time I would hear him speak, even about things really casually, he was always very paced, very measured, very contained and always really specific about things he said, because he definitely wanted his views to be understood.”

For a former athlete who fell out of love with basketball because of the culture of competition, the zero-sum game of wins and losses, Mr Ali is gently competitive with himself, to become a better actor, a better partner, a better person.

“In acting, in art,” he says, “it’s not about out-acting anyone, but how deep you can go, how good a collaborator you can be. “I think when you are constantly checking in with yourself, we develop a skill, a call and response. If we’re willing to look inward,” he says, and now I think he’s begun to talk about life, as well as the work, “I think we know if we can do better, or if we can be more.”

Green Book is out now (US); out 15 February (UK)