THE JOURNAL

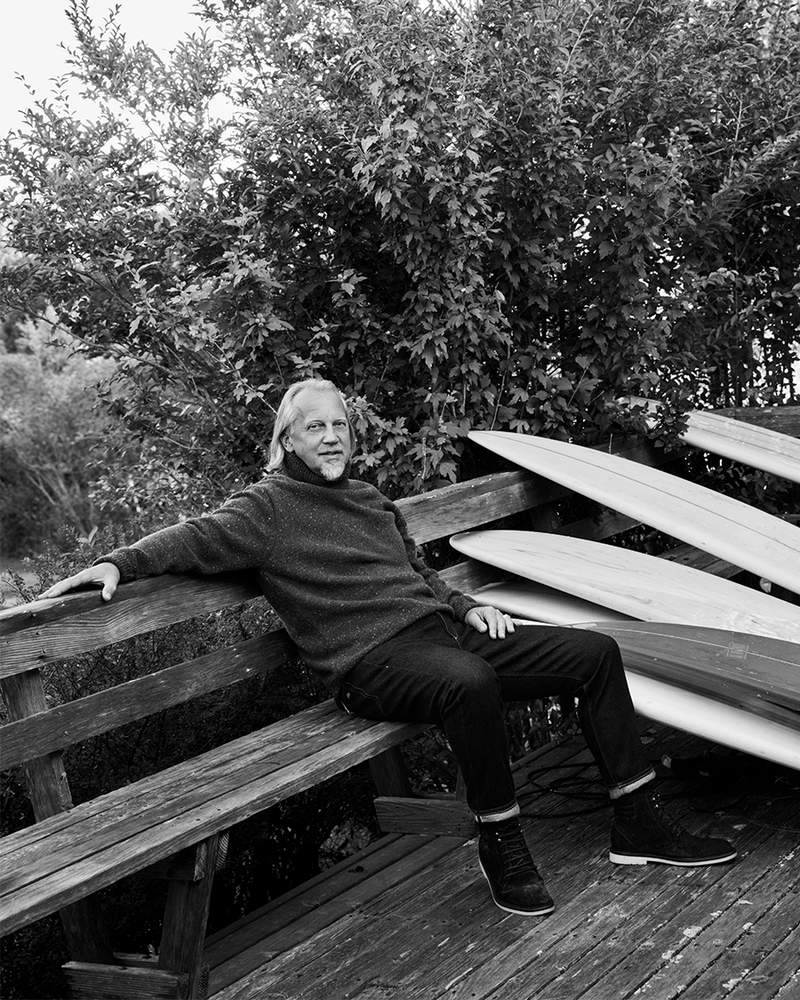

Mr Stephen Alesch in the garden of his reborn 1950s home in Montauk, New York

“Nothing ever really dies,” says the designer and architect Mr Stephen Alesch. He’s talking about his late friend Mr Anthony Bourdain, and what was to be a massive food hall along Manhattan’s West Side on which they were collaborating. He says it with a glint of irony, but he also kinda, sorta really means it.

A wander around the Montauk home Mr Alesch shares with Ms Robin Standefer, his wife and partner in their design firm Roman & Williams, will give you a good idea of the way things can live on in his world. The tambour wall separating the living room and kitchen? A bit of scrap material from the lush, Bentley-in-the-sky-vibe nightclub (formerly known as the Boom Boom Room) at the top of The Standard in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District, designed by Roman & Williams. The trapezoidal plywood chandelier in the living room – picked up for $50 on Lafayette in NoHo (“at a junk shop that used to be where the rapper tennis shoe store is now, the fancy one,” he says, meaning Kith) – could be mistaken for one of Ms Charlotte Perriand’s pieces. It’s actually from a Denny’s (“or maybe a Bob’s Big Boy”), and inspired the organic modernist chandeliers Roman & Williams made for the Freehand hotel lobby in Los Angeles. Even the long dead – or dried – white hydrangeas that Mr Alesch and Ms Standefer adore have really only found their final aesthetic form here in their fall, coppery-toned afterlife. Here, everything is reborn.

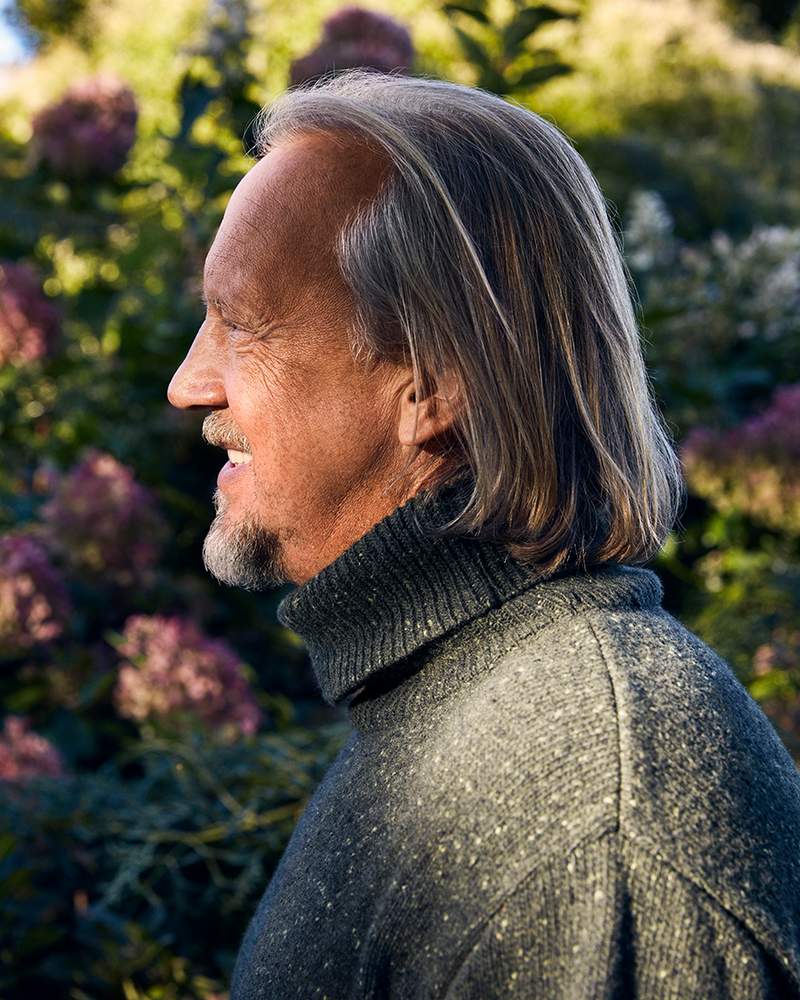

Mr Alesch’s studio, where every Monday, he works his “ass off in silence, barefoot”

In his drawing studio, Mr Alesch likes to keep all of his art supplies to hand

And, in a way, Mr Alesch himself came to this cliffside home at the end of Long Island to be reborn. Not long into the new millennium, he tells me, “I started to say, ‘Robin, I don’t think I can live [in New York City] anymore.’ I mean, my skin looked like the colour of this bowl,” he says, referring to a white piece of their crockery. “I was fat. I was sluggish. I wasn’t surfing, and so I went out to Montauk and just kind of fell in love with it. You feel it when you are driving out, when you hit Montauk, it just feels weird. There’s a slightly fugitive quality. Shirts come untucked, and it’s like, people sleep a little later in the day or something. I mean, everything starts to change somehow, like it does when you go into the canyons where I grew up.”

Mr Alesch, who now sports a page boy ’do to go along with his deep surfer’s tan, grew up in the hilly, wild northwest of Los Angeles, in the coin-purse canyons above Malibu, up winding roads that give way to dry, kindling landscape. It’s an area that was then famous for being inhabited mostly by biker clubs and mountain lions. After bouncing around high schools in California and Arizona, he began working in architectural offices at the ripe old age of 18. “I call myself the Doogie Howser of architecture,” he says. “But because I started in architecture so young, by the time I was 26, I was like, ‘Oh my god. This is so freaking boring.’”

He wandered his way into film and there, while working as a set designer, met Ms Standefer, who was a production designer. “No one can command a room like Robin,” Mr Alesch says. “[Whether it is] her presentation to a hotel group, or winning the confidence of 14 sceptical, nervous studio people.” But after 10 years in the biz, he says, “we were a little worried. We knew some older people who worked in film, and they were just exhausted, a different kind of exhaustion. They were, like, homeless. It’s a tough industry to grow older in, I think.”

In 2001, the couple took an inspiration trip to India, and when they returned, Mr Alesch says, “we kind of convinced Ben [Stiller] to let us redo his house, based on a beautiful set of drawings I did over a weekend”. Mr Stiller had been a collaborator with the couple on several films including Zoolander and Duplex [Our House in the UK], and these first commissions, Mr Alesch says, helped them pivot towards their new career. “Ben was really a patron,” Mr Alesch says. “Our first architectural patron.”

By this point, it was the mid-2000s – a time Mr Alesch refers to as, the “beige era, pseudo Zen”. When Roman & Williams was coming on to the scene, everything in architecture and design looked a bit same-y, a bit Unhappy Hipsters in a Dwell magazine editorial. And what Mr Alesch and Ms Standefer were doing for their early clients was… not that. Their creations were cinematic, rich, like maximalist Dutch Masters paintings, or cabinets of curiosity as living spaces.

I think over-design is a little fatiguing. If you think about it, design only exists in cinema as a sign of corruption. It’s a sign of someone who’s lost their way. A Bond villain

As Mr Alesch describes it, this difference is fundamental to who they are and what Roman & Williams (named after the couple’s grandfathers) stood for. “I know we’re designers,” he says, “but we have this aversion to design-y-ness that has always made us cringe. I think over-design is a little fatiguing. If you think about it, design only exists in cinema as a sign of corruption. It’s a sign of someone who’s lost their way. A Bond villain. I don’t even have a word for [Roman & Williams’ style]. I mean, I personally use a weird word, schöpfung, which is German for ‘creation’. But it literally means more like ‘fell out of the sky_’_. Something that just exists without you, like God made it. It’s just nothing extraneous, nothing silly, nothing egotistical. No super villain in that.”

Whatever you call it, Mr Alesch and Ms Standefer’s early interiors work (for Mr Stiller and a gaggle of other celebs) brought about a sort of firestorm of success and commissions, including long standing partnerships with The Standard, Ace Hotel and Freehand – and even a commission to redesign the British Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – as well as dozens of restaurant and residential designs. In 2017, they launched Roman & Williams Guild, a line of, hand-hewn housewares that we are thrilled to be debuting on MR PORTER this week.

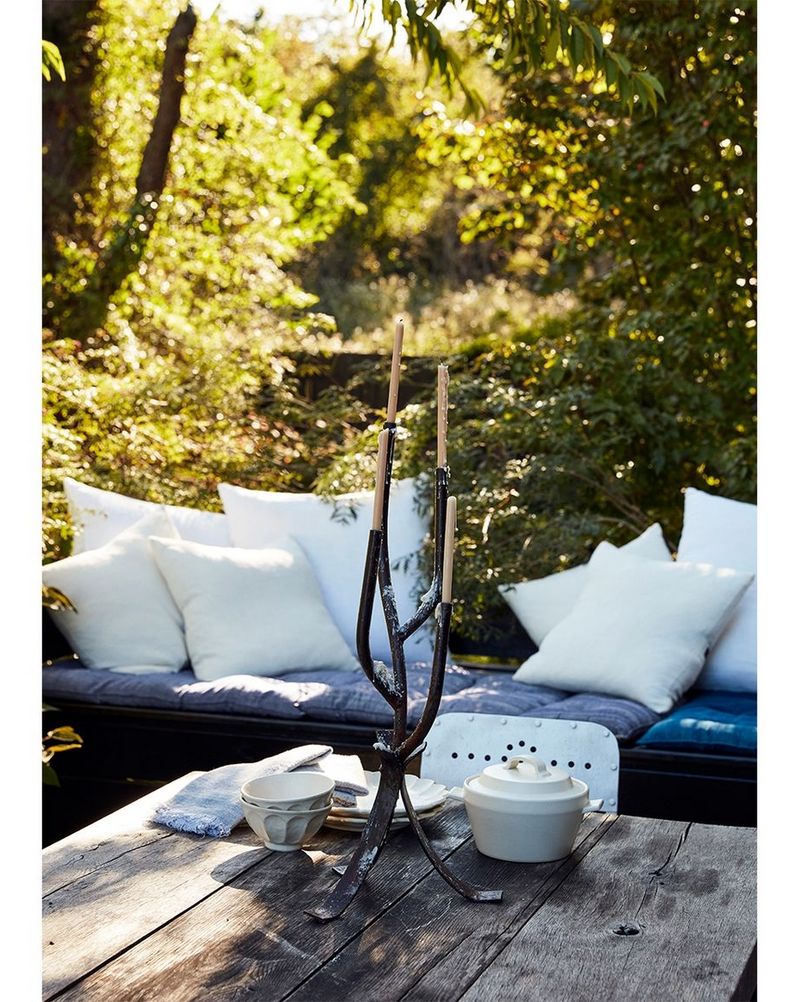

Most of the furniture in (and around) the home was handmade, serving as prototypes for the Roman & Williams Guild range

“We want to share more,” Mr Alesch says, “and we have these projects – these great hotel projects, these private homes that take five or six years to kind of put together – which are amazing, but sometimes you want to give things out in a more democratic way. Our appetite is huge. Our appetite to collect, arrange and share, with architecture, small objects, plants, foods… I think we have a generous spirit. We just want to share as much as possible, with as much people as possible.”

Weekend dinners around the weathered patio table in Montauk, surrounded by a garden in riotous bloom, are a great opportunity to share both their generosity and their wares with friends. “Montauk’s always been a laboratory for us, of who are we, or what our world looks like client-free,” Mr Alesch says.

You feel it when you are driving out, when you hit Montauk, it just feels weird. There’s a slightly fugitive quality

“This is the first house we ever bought, you know? It was a stripped 1950s house when we bought it. It didn’t have a lot of character. Aluminium windows, sliders, drywall everywhere, can lights, nothing. We ripped everything out, and just never finished the house like a project. We just put it together piecemeal, fragmented. Our apartment in the city was just layers of flea-market shopping, stuff we collected over the years. But Montauk started becoming about making furniture. We’d get out there and be like, ‘Let’s renovate the studio this weekend, right?’ And out of that work came prototypes for the [Roman & Williams Guild] work... Most of the furniture you see here is sort of really well-built versions of the prototypes, a fine manifestation of a primitive idea that was born next to that campfire on a rainy spring weekend.”

From rainy springs to golden falls, Mr Alesch and Ms Standefer have, over the years, settled into a kind of weekly routine. When not travelling for work, they spend Tuesday through Thursday in the city, “just balls out meetings, corrections, drawings,” Mr Alesch says. But, “it’s very hard for me to draw in the city anymore. I can’t have the psychic quietude that I used to be able to achieve.” So, come Friday, they vamoose to where it gets weird. Saturday and Sunday are spent in the garden, painting, tinkering, entertaining. And then, Monday, “that’s our studio day, we call it, where we work our ass off in silence, barefoot. Robin’s upstairs. I’m downstairs. We hardly see each other until nightfall. We don’t eat breakfast. We don’t eat lunch. Yeah, I lost a bunch of weight doing that. It’s awesome. And I come back Tuesday morning with rolls of drawings.”

Back in the city now, Mr Alesch is being whisked away to a travel magazine awards dinner at which he and Ms Standefer are to be honoured. He is in his polished city mode: blue suit and brown boots, navy Mackintosh. But he is already dreaming about being back in Montauk where he can again dress like a “caveman, barefoot in a sarong”, where he can draw and paint and create, and where he has the power to breathe life, at least into his creations.

“Our lives. We’ve done tonnes of work on paper, and spent years with our amazing clients, working on conceptual projects, that, to be honest, still live in my mind. Like working with Anthony on four different versions of that market,” he says, referring back to Mr Bourdain. “I mean, I did drawings the size of this table of every stall, and renderings with thousands of people cooking and eating. I know Anthony’s gone, but to me he’s not dead. His project’s not dead. I do think it will be built by him someday somewhere. I’m that irrational. It’s kind of how I deal. I just don’t believe anything’s ever really finished. Nothing’s ever over.”