THE JOURNAL

Chuck Taylor x Converse, Chuck Taylor All Star. All photographs courtesy of Rizzoli

Why are we all so obsessed with sneaker collaborations? What can they tell us about our culture? How do they shape masculine identity? These are the questions Ms Elizabeth Semmelhack, a shoe historian and senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, seeks to answer in her new tome Sneakers x Culture: Collab, a chronology of the most historically significant and hype-worthy sneaker drops featuring interviews with the world’s most respected collectors, connoisseurs and designers.

The author became interested in sneaker heritage and culture when she told people what she did for a living, and they all assumed she worked at a women’s museum and not a shoe museum. “We don’t differentiate gender by having women wear shoes and men going barefoot!” she tells MR PORTER. And, so, she started to research a genre of footwear historically entwined with masculinity: sneakers. We’ll let her explain the rest.

___

How does the story of sneaker collaborations start?

It really starts in the 1930s – [that period] presented a very difficult economic environment and, given that there were fewer dollars to be spent, companies had to conceive of ways to distinguish their products. I think that the Jack Purcell x BF Goodrich is the perfect example of that. Commercialised sneakers at that point were canvas-uppered, rubber-soled things, so companies had to create differentiation. Working with Purcell, having him weigh in the construction of the shoe and then promoting that fact was a way of differentiating. It also took into consideration the ideas of an “expert”.

___

Jack Purcell x B.F. Goodrich, Jack Purcell

___

How do you define a collaboration?

I try to differentiate between a “signature” shoe and an actual collaboration. The [Converse] All Star came out in 1917, but, in 1934, in the midst of the depression, Chuck Taylor’s name was added to the shoe. He was such a famous promoter of basketball itself and of Converse, so having his name on the shoe helped bring a fresh interest to a long-standing brand and style. That formula, if you want to call it that, was available to companies moving forward but it doesn’t get full traction until the late 1990s, early 2000s. And now it has exploded.

___

How do you characterise the relationship between sneaker collaborations and wider cultural shifts?

This is a question I wanted to grapple with in the book: why is collaboration so hot right now? There are so few items of dress that are allowed to carry a narrative. I think this is something that sneakers – and in particular collaborations – do very well. Sneakers are not blank canvases: some collaborations are not creating completely new sneaker architecture; some are taking historic models and working with all of the cultural information that’s embedded in them to do something new.

___

You mention in the book that sneaker collaborations are responsible for reigniting interest in heritage styles. Why do you think that is?

What’s interesting about the people who are really devoted to sneakers is that they are really interested in the history of sneakers. For the “cognoscenti” of sneaker culture it goes beyond simply saying “Oh, that’s an Air Jordan I”; they want to understand when it became an Air Jordan I, how many retros there have been and so on. Each collaboration that uses an Air Jordan I, for example, plays on this long history. I think in many ways sneaker collaboration culture is like traditional Japanese haiku, which is a very standard format – but the most brilliant examples are ones that use a previous poem and then add an unexpected twist. So, for those in the know, it’s delightful. It’s an “Oh, I see what you did there!” moment.

___

Is that what makes sneaker collaborations so covetable?

There are multiple factors. There are people who can delight in them. But also, increasingly, we are allowing men to express individuality through dress, which we have previously discouraged. Sneakers are a very interesting accessory that can maintain traditional concepts of masculinity while at the same time allowing for newer forms of individual expression. If you’re an individual, you need to have choice. Collaborations add to the mix of sneaker choices out there. And because collaborations often bring together known entities, they lace the sneakers with complex narratives that can make these objects much more compelling.

___

Kaws x Jordan Brand, Air Jordan IV Retro

___

Narrowing down countless collabs can’t have been a straightforward task. How did you decide on the ones that made the cut?

It wasn’t easy! Obviously, I wanted to offer as many examples from history as possible… but I also wanted to include a variety of people, from musicians to artists to high-fashion designers. It was a matter of making sure there was a balance. It includes many of the most coveted examples, like the Eminem x Air Jordan IV or the Kaws x Air Jordan IV. Kaws is an excellent example of an artist who is complicating the traditional relationship between high art and consumables. He traverses so easily across so many borders or artificial boundaries. I included him because his collab was so important, but I also included him because of interest in that story.

___

What does the future hold for sneaker collaboration?

I ended the book with Les Benjamins [x Puma Thunder Disc] for a reason. He’s [Les Benjamins founder Bunyamin Aydin] centred in Istanbul and one of the things he said to me during our interview was that he felt at the periphery [of sneaker culture]. There are so many rich stories that could be told linking traditional Turkish culture to contemporary sneaker culture, and he was so eager to be able to combine these things. It as a realisation that, while people can focus on the brute economics of collaboration, if we understand what collaboration really is, and if we agree that sneakers can be a place where voices are heard, there’s the possibility of seeing new, more interesting stories.

___

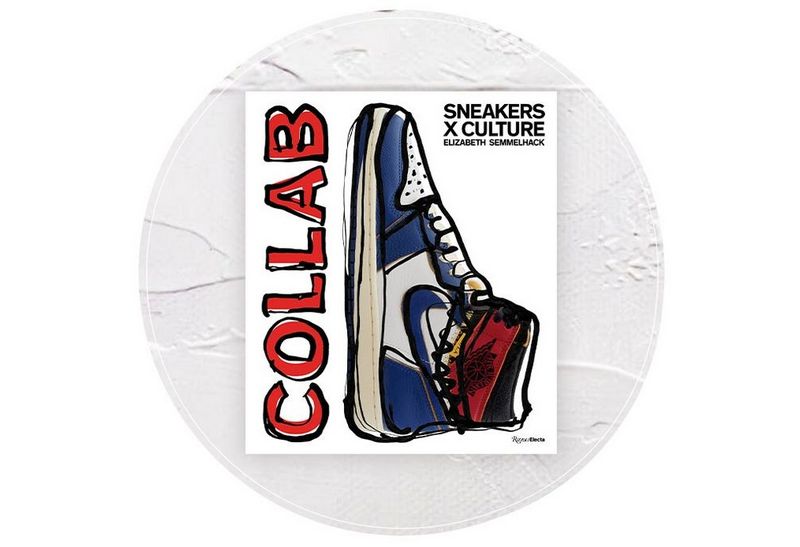

Sneakers x Culture: Collab by Ms Elizabeth Semmelhack. Image courtesy of Rizzoli