THE JOURNAL

Mr Joaquin Phoenix in Joker (2019). Photograph by Mr Niko Tavernise, courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc

Joker, the defining divisive film of the moment, is a fascinating Rorschach test for contemporary cinematic masculinity. It received the Golden Lion and an eight-minute standing ovation at Venice (a festival with its own history of phallocentrism) and has made nearly US$1bn worldwide. But it’s also been denounced as shallow, derivative, cynical, incel-friendly and a crude depiction of mental illness. So incendiary was its pre-release buzz that one US cinema chain banned masks, face-paint and costumes at its screenings for fear of copycat attacks. A few months after Mr Quentin Tarantino’s equally provocative Once Upon A Time in Hollywood, it begs the question: is the age of the “man” film over?

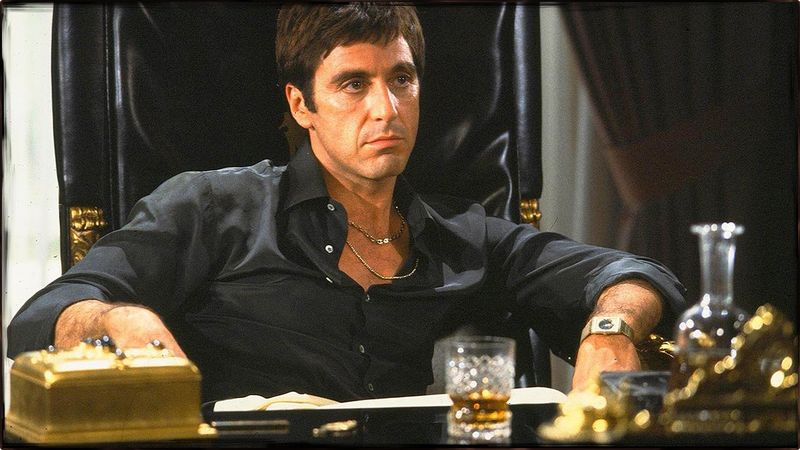

By “man” film, I mean the sort of film that shows a white man channel his disenfranchisement into violence with an infectious dress sense, old-and-new soundtrack and grandiose worldview – a sort of invincible, couldn’t-give-a-fuck nihilism crystallised by a breakthrough role for a zeitgesty actor (Mr Malcolm McDowell in 1971’s A Clockwork Orange; Mr Brad Pitt in 1999’s Fight Club). It has been an undeniably successful formula for cinema, but sexual politics are often stunted, with limited agency for women (in Scarface, Mr Al Pacino’s Tony Montana describes Miami as “one giant pussy waiting to get fucked”). If Ms Margot Robbie is in the film, she will no doubt be underused.

Mr Brad Pitt in Fight Club (1999). Photograph by Twentieth Century Fox/Allstar Picture Library

“Man films” are alpha-geek fairytales, retro riffs on old movements and male behaviour. Pulp Fiction combines the formal playfulness of French 1960s cinema with a reinvented 1970s idol (Mr John Travolta). Joker cements its debt to Mr Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and The King Of Comedy (1982) by casting Mr Robert De Niro as the figure Joker wants to be. Once Upon A Time In Hollywood is an elegy for late 1960s LA and when men could be men, even one who might have killed his wife. Mr Scorsese’s The Irishman literally de-ages its illustrious leads.

Another theme is the desire to be taken seriously. Mr DiCaprio’s Rick in Once Upon A Time resents that he’s reduced to crappy TV westerns. Joker wants to be a stand-up who elicits the right kind of laughter. Mr Todd Phillips’ own directorial evolution from outlandish comedies (Road Trip, Old School, the Hangover trilogy) to Joker has its own parallels.

As one commentator sagely tweeted, Joker feels reverse-engineered to be “iconic”, printed on dorm posters and mimicked at fancy-dress parties (the make-up, the suit, the dance on the stairs). The depiction of its social setting (“Is it just me or is it getting crazier out there?”) is vague enough to find resonances all around the world (from Wall Street to Hong Kong), but too woolly to say anything insightful. It’s also a rare “superhero” film told from the point of view of the villain, at a time when appetites to see killers humanised are particularly low.

Mr Al Pacino in Scarface (2006). Photograph by Universal/Landmark Media

Generally, the “man film” does very well financially; The Wolf Of Wall Street is Mr Scorsese’s most profitable film. The danger is they can be appropriated less ironically than they are intended, or by the people they aim to subvert. Social media empowers both the backlash and the forum to defend oneself (anonymously, if necessary). That more rigid public moral code is undoubtedly a force for good, but can also punish mistakes with greater glee.

Even President Obama, that much-missed ideal of masculine authority, recently questioned the limits of call-out culture, arguing that it’s not activism just to publicly highlight the mistakes of others to paint yourself in a better light (this, in turn, has been dismissed as “boomer” thinking, the latest insult for fogeyish liberalism. You can’t win).

Economics suggest, then, there will always be a market for this type of film, though it may be from older, more nostalgic audiences. Teenagers today seem more sensible, empathetic and quicker to call out injustice, from gun violence to climate change. Though it only came out in 2013, I’m not sure Mr Scorsese could make The Wolf Of Wall Street now (the ominously “immersive” live stage show has had an even greater backlash than the original film). It already feels like a less cathartic experience now the guilty-pleasure fantasy has become a dangerous reality, where the most powerful (rich white men) masquerade as the disenfranchised and the two bleed into each other at the expense of the genuinely marginalised.

Mr Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf Of Wall Street (2013). Photograph by Red Granite Pictures/akg-images

Man films are also increasingly infrequent and repetitive, a diminishing circle of self-cannibalising variations on the same themes and faces whose masters won’t go on forever. Mr Scorsese is 77 on 17 November. Mr Tarantino has said he only intends to make one more film. Even the future of the once-untouchable James Bond is being interrogated, with creative disagreements on the new film and growing calls to diversify the casting of the next 007.

At a time when men can always do better, nasty, angular masculinity is not in vogue. It’s fine to feel weak and frustrated and confused, and cinema can expunge that. But it might be even healthier to evolve than double down, create a brand new grammar rather than reminisce and imitate. Just as lad mags became extinct, a subtler way to shape future generations of men can be the new equivalent of these kinds of film. I’m quietly hopeful the next generation will gravitate to equally stylish, more emotionally nuanced depictions of conflicted masculinity – such as Top Boy, Watchmen, Peaky Blinders and Moonlight. Either way, I can’t help but think a female Joker would have been even more compelling.