THE JOURNAL

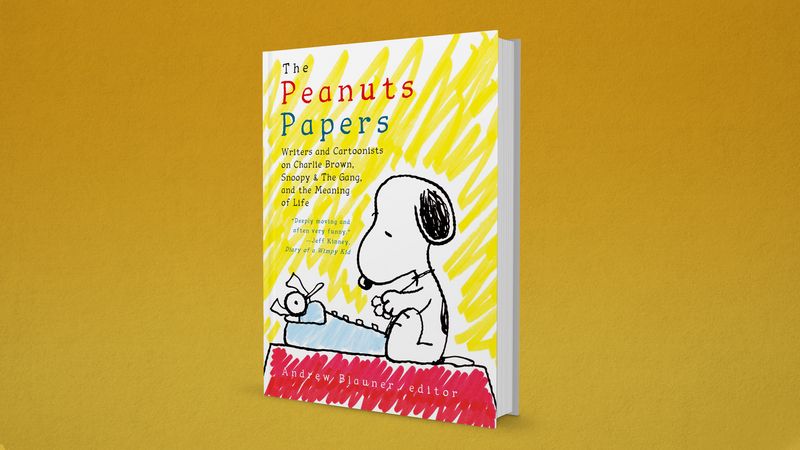

The Peanuts Papers by Mr Andrew Blauner. Image courtesy of Library of America

“Among the thousands of life lessons found throughout Peanuts, I believe there is one that stands out among the rest,” writes author, cartoonist and The New Yorker contributor Ms Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell in The Peanuts Papers, a new collection of essays and drawings on the work of Snoopy creator Mr Charles M Schulz. “At the end of the day, you can either be disappointed, or you can be dancing, but you cannot be disappointed while you’re dancing. So, take your pick.”

In the 50 years up to his death in 2000, Mr Schulz penned 17,897 Peanuts strips. At the peak of his powers in the mid-to-late 1960s, his cartoons featured in 2,600 newspapers globally, reaching 355 million readers in 75 countries. Ms Sarah Boxer, who wrote Mr Schulz’s obituary for The New York Times and is among the 33 writers and artists to contribute to The Peanut Papers, quotes popular culture scholar Mr Robert Thompson’s assertion that the strip was “arguably the longest story told by a single artist in human history”. But behind the series’ success sits a contradiction: at its core, Peanuts was about failure.

Judging by the lovingly assembled assessments that make up this volume – which takes in authors, cultural thinkers and, in Mr Chris Glass and Seth, like Ms Fitzgerald Campbell, creative minds so inspired by Mr Schulz that they wound up drawing cartoons for a living – that underlying sadness is actually what brings people together, if alone, reading Peanuts. In his contribution, This American Life presenter Mr Ira Glass draws on a quote from Mr Schulz himself that captures Mr Glass’ own feelings about the series: “All the loves in the strip are unrequited… All the baseball games are lost, all the test scores are D-minuses, the Great Pumpkin never comes, and the football is always pulled away.”

“That’s the dark-but-happily-dark feeling I got from reading Schulz’s strip,” Mr Glass notes. “It’s still there today, waiting for me if I have a bad week, like a bad robot ready to come to life.”

Semiotician, philosopher and social critic Mr Umberto Eco went further in his essay from 1963, just before Mr Schulz really hit his stride. In his piece, included in the book, Mr Eco suggests that the characters that populate the suburban playgrounds of Peanuts are manifestations of all of our own very adult fears. “These children affect us because in a certain sense they are monsters,” the author of Foucault’s Pendulum writes. “They are the monstrous infantile reductions of all the neuroses of modern citizen of industrial civilization.”

Novelist Mr Jonathan Franzen came to Peanuts during the late 1960s, Mr Schulz’s imperial phase, before, to The Corrections author’s mind, “he began to drift away from aggressive humour into melancholy reverie”. Although by Mr Franzen’s own account, the strip was already well on its way to “corruption by commerce”: “if my own friends were any indication, there was hardly a kid’s bedroom in America without a Peanuts wastepaper basket or Peanuts bedsheets or a Peanuts wall hanging. Schulz, by a luxurious margin, was the most famous living artist on the planet.”

At the tail end of the 1960s, a time when the US was perhaps more divided even than now, Mr Franzen argues that the strip still managed to hit a sweet spot where it somehow appealed to everyone. “To the countercultural mind, the strip’s square panels were the only square thing about it. A begoggled beagle piloting a doghouse and getting shot down by the Red Baron had the same antic valence as Yossarian paddling a dinghy to Sweden,” he says, putting it in the same bracket as Mr Joseph Heller’s satirical WWII novel Catch-22, which came to embody the younger generations’ attitudes to the Vietnam War. “This was the era of flower children, not flower adults. But the strip appealed to older Americans as well. It was unfailingly inoffensive… and was set in a safe, attractive suburb where the kids… were clean and well-spoken and conservatively dressed. Hippies and astronauts, the rejecting kids and the rejected grown-ups, were all of one mind here.”

With its cross-generational themes, younger readers were exposed to sophisticated notions – in the most simplistic form – that might only make sense later in life. “Peanuts comprised a killer introduction to minimalism, to the idea that, to cover vast emotional territory, art need not be catalogic or vast,” writes Man Booker Prize-winning author Mr George Saunders. “Years later, first encountering Beckett, I felt on familiar ground: two guys talking about loss and futility while standing in front of a tree was not so different from two round-headed kids talking about loss and futility while standing behind a brick wall.”

Mr Eco, too, compares the inbuilt sorrows of Mr Schulz’s children to the work of Mr Samuel Beckett. The ongoing misery of Charlie Brown is such that it spawned a running gag in Arrested Development, but Mr Eco shows a greater pity for his pet beagle: “A constant antistrophe to the humans’ suffering, the dog Snoopy carries to the last metaphysical frontier the neurotic failure to adjust. Snoopy knows he is a dog: he was a dog yesterday, he is a dog today, tomorrow he will perhaps be a dog still. For him… there is no hope of promotion.”

And yet, Snoopy is the one character who always instigates the dancing. He might know his place – even if he often daydreams that he’s somewhere or someone else, he always returns to the doghouse – but he also knows how to move his feet. “He may never be satisfied with life or food,” Ms Fitzgerald Campbell adds, “but dancing is one guarantee of a good time.”

And as Ms Fitzgerald Campbell mentions, this might be the ultimate takeaway from the longest story ever told by one man: “What is life but a series of small disasters with a little dancing in between!” she concludes.

The Peanuts Papers (Library of America) edited by Mr Andrew Blauner is out now