THE JOURNAL

The ultimate recipe for the traditional dessert – and the secret ingredient you need to know.

Although pumpkin pie is an American stalwart, it is a French invention, or at least, the first recorded recipe is by a 17th-century French chef – and, well, the French do know a thing or two about patisserie. Soft and sweet, squashes make excellent desserts, especially at this time of year when homegrown fruit doesn’t extend much beyond the apples and pears we’ll be munching on until next spring.

And though historians agree that the Pilgrim Fathers were probably too busy with the whole survival thing to have tucked into pumpkin pies at that first Thanksgiving feast, they’re now as much a part of the celebrations as roast turkey and the Macy’s Parade. And even if you are not in the US, pumpkin season is a great excuse to gatecrash the party. Crack open the hard cider, stick the big game on and see if you can make a few converts to the best round orange thing to come out of the US in… well, forever. Here are a few simple tips to making pumpkin pie great again.

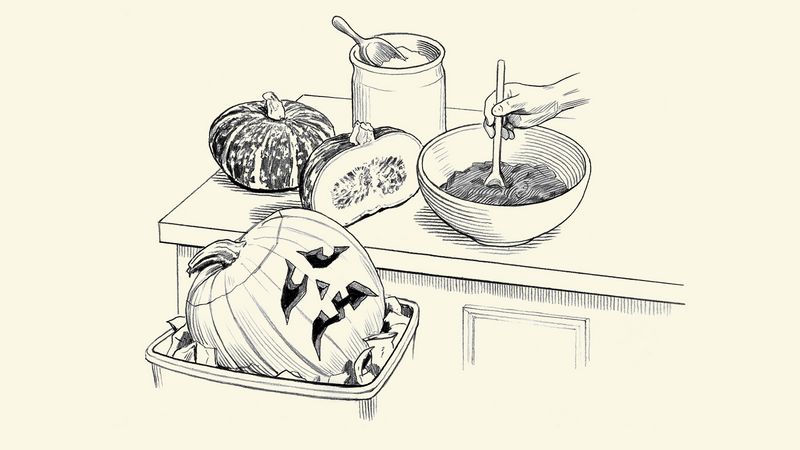

01. Ditch the pumpkin

Yes, you read that right. The orange monstrosities that have been haunting shops since well before Halloween are bred to be brilliant jack-o’-lanterns – so big, so smooth, so brightly coloured! – but flavour doesn’t come into the equation. Terrifying trick or treaters is one thing, but there’s no need to scare your nearest and dearest with their bland, stringy flesh, too. “Culinary pumpkins” are increasingly available, but I’ll let you into a little secret – most of the millions of tins of pie filling sold in the US every year don’t contain Cucurbita pepo, otherwise known as “true pumpkins” at all, but their close relatives Cucurbita moschata, a species that that produces lighter-coloured, more elongated and – importantly! – tastier fruits, such as, for example, the butternut squash. Farm shops and markets are full of different varieties at this time of year: choose something that feels dense and heavy for its size (kabocha and kuri are two I’ve had success with in the past), or if you’re hitting the supermarket, you can’t go wrong with the trusty butternut.

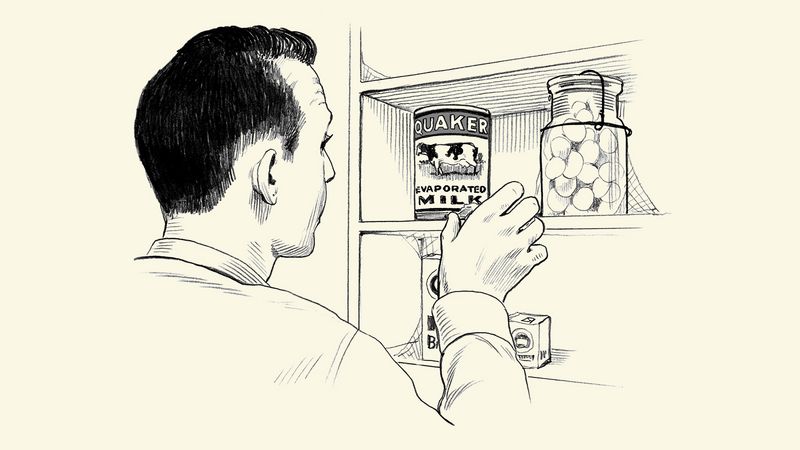

o2. Leave your snobbery at the door

You may personally favour almond/full-fat/unpasteurized/organic milk, but leave your prejudices to one side and reach for that tin of evaporated milk. Yes, the same stuff your granny used to pour over tinned peaches and call fruit salad – it’s essential for a creamy, but featherlight custard. Trust me on this – you won’t find a better alternative anywhere.

03. Make cinnamon your friend

Sugar and spice and all things nice may be fine for little girls, but pumpkin pies prefer maple syrup to give them that quintessential New England sweetness. Embrace the pumpkin spice, though; it may have no place in a cup of coffee (and I’ll fight anyone to the death who claims otherwise), but the warmth of cinnamon, ginger and cloves work brilliantly with the sweetness of squash (or, indeed, pumpkin). I’ve also added a little nutmeg on top, in homage to your classic British custard pie.

04. Avoid a soggy bottom

The joke may have worn thin long before The Great British Bakeoff came on TV, but the fact remains: raw pastry isn’t anyone’s cup of tea (though maybe it pairs well with a Pumpkin Spice Latte). Blind baking your pastry crust before pouring in the pumpkin custard will ensure the kind of crisp, autumnal result that will have even the most exacting Thanksgiving guest purring with pleasure.

o5. Don’t forget: everything’s better with rum

More a general rule for life, if I’m honest, but don’t be shy when adding a generous slug to the custard here: those old pilgrims liked a cider or two, even if the US briefly turned its back on booze a few centuries later (bringing some of the world’s finest bartenders to Europe, I might add). The sweetness of golden rum is ideal, but good ole’ Southern bourbon would also work very well indeed, and you might also enjoy a little celebratory sip while you’re tucking into the pie – though it also pairs well with cider, spiced ale, or a sweet sherry or tawny port. Yes, there’s a lot to be thankful for here.

The recipe

Makes 1 x 20cm tart

For the pastry:

170g plain flour Pinch of salt 100g cold butter 2 tbsp caster sugar 1 egg yolk For the pie filling:

1 medium squash, butternut or otherwise, or 1 small culinary pumpkin (roughly 1kg) 145g maple syrup 1 tsp cinnamon ½ tsp ground ginger 5 cloves, ground 1 nutmeg, to grate 3 tbsp golden rum or bourbon 2 large eggs, beaten 150ml evaporated milk

01.

Heat the oven to 200ºC and cut the squash into quarters. Scoop out the seeds and discard, then put in a roasting dish, skin side up, with a splash of water so it doesn’t stick. Bake for about 30 minutes, or until tender, then allow to cool slightly.

02.

Peel off the skin, then put the flesh in a food processor and whizz to a smooth puree. Place in a fine sieve above a bowl, and leave to drain for at least an hour, pressing it against the sieve occasionally to encourage more liquid out.

03.

Meanwhile, make the pastry. Lightly grease a 20cm tart tin at least 3cm deep. Put the flour in a mixing bowl with the salt, then grate in the butter. Rub in with your fingertips until it looks like breadcrumbs, then mix in the sugar. Whisk the yolk with a splash of cold water, just too loosen it, then sprinkle just enough of it into the dough, mixing all the while, that it comes together into a ball.

04.

Roll out the dough on a lightly floured surface to about the thickness of a pound coin, then use to line the tin. Prick all over with a fork, then cover and chill for half an hour.

05.

Heat the oven back up to 180ºC and line the pastry with greaseproof paper. Fill with baking beans and bake for 15 minutes, then remove the beans and paper and bake for a further 5 minutes until lightly coloured.

06.

Meanwhile, put 250g of the pumpkin puree (you can chuck the liquid) in a bowl and stir in the syrup, spices and booze. Taste for sweetness and spice, adding more of anything if needed, then whisk in the eggs and milk.

07.

Pour the custard into the pastry case and top with a generous grating of nutmeg. Bake for about 30-40 minutes, checking from half an hour onwards, until the filling is set, but still slightly wobbly in the centre. Allow to cool for at least 30 minutes before serving.

What to wear

Illustrations by Mr Joe McKendry