THE JOURNAL

Photograph courtesy of Magpie

Expert advice to help you help you with that dream job.

We all dream of being our own boss or successfully executing a business idea. And owning a restaurant can seem like a particularly romantic proposition. The facts, however, tell a more cautious tale. According to Harden’s London Restaurants, despite the number of restaurant openings in the British capital reaching a record high last year, closures were up by a third. Competition in the market is increasing with the rise of the food-to-go sector. And the depreciation of the pound following the Brexit vote has made finding staff more difficult. So, in a volatile market, how do you succeed when you open a restaurant?

01. HAVE THE RIGHT IDEA

“It’s damn hard work,” says Mr Adam Hyman, founder of CODE, a magazine, online resource and consultancy for the hospitality industry. “It’s an all-consuming career. There is no such thing as a nine-to-five restaurateur. It requires long hours, and it’s physically tough.” You also need a solid idea, of course. And those who prosper seem to stick to what they know.

One such man is Mr Martin Morales, who forged a successful career at Apple and then Disney before quitting to open the pioneering Peruvian restaurant Ceviche in 2012 – his new book, Andina: The Heart Of Peruvian Food, is out now. “When I was four years old I travelled to Santiago de Chuco in the Andes Mountains in Peru,” he says. “Along the way… we stopped by a picanteria – a family run restaurant. I’ve never forgotten the flavours, ingredients, love, generosity and welcome that I felt on that day and I dreamt that if only I could bring a little bit of that to London one day, I’d be a happy and maybe even successful chef.”

Mr Sam Herlihy found success after a change of career when he co-founded Pidgin in Hackney in 2015 – which expanded on a simple, tried and tested idea. “I was the singer in a pretty miserable indie rock band [Hope Of The States], touring the world and drinking far too much,” he says. “I’d always been interested in food and cooking and it seemed like a good place to carry on drinking far too much.” After meeting his business partner Mr James Ramsden, they worked on a supper club together, which they knew could work as a restaurant. “We wanted it to be a continuation of the communal, set-menu based situation of the supper club,” says Mr Herlihy. It gained a Michelin star within two years of opening and he and Mr Ramsden have since gone on to open Magpie in Mayfair.

02. THINK TIMELESS

Another key pointer is to avoid chasing trends. “You see restaurants date so quickly these days,” says Mr Hyman. “It’s all about creating timeless restaurants. This is why Corbin & King, who own The Wolseley, are two of the best in the business. Of course, you need to adapt and stay relevant, but I don’t think it’s about carving an unexpected niche.”

“The restaurants that perform the best are ones that are an extension of the people who work there,” says Mr Will Lander, owner of successful restaurants The Quality Chop House, Portland and Clipstone. He cites Moro and Morito as “shining beacons of independent restaurants” that have done well by this philosophy. Clarke’s in Kensington and St John in Smithfield are two more he admires. “They all share an aesthetic, ethic and a rigour that they stick to and it’s born out of their love of cooking and hospitality. I don’t think [the founders of Moro] sat down in 1994 and said: ‘I think what London needs is a North African/Spanish peninsula restaurant on Exmouth market.’ They just did it because they loved it.”

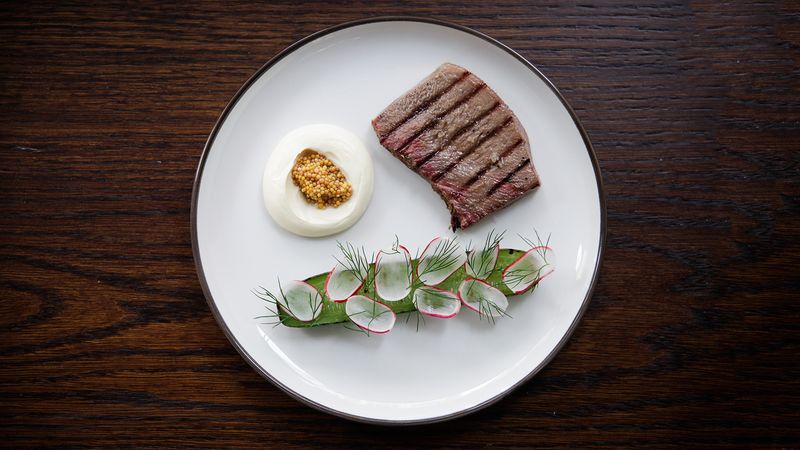

Grilled ox tongue, cucumber, creme fraiche and pickled mustard seeds. Photograph courtesy of Clipstone

03. THINK BEYOND THE FOOD

“I always maintain that the hospitality is more important than the food,” says Mr Hyman. When asked about the biggest challenges facing a would-be restaurateur, Mr Herlihy says: “Dealing with people. Money and getting customers through the door are slightly more intangible things, but the day to day of finding the right staff and keeping them happy, engaged and on-board with how you want things done is what you spend the vast majority of your time doing.” This is why it’s so important to surround yourself with the right people, says Mr Lander. “I’ve known my business partner since I was 10. A lot of trust and shared principles are the most important things.” Others in the industry agree that a good staff is vital. And not just in the kitchen.

04. RAISE THE FUNDS

All this is irrelevant, of course, if you can’t find any money to fund your idea. Crowdfunding, family savings and bank loans are all viable avenues, but restaurants can present an exciting opportunity for a private investor. “People who have huge amounts of disposable income and an eye for an investment tend to be people who also like going to restaurants,” says Mr Lander. “There are also economic circumstances that mean putting money into a bank won’t do much for them.” But how might one meet an investor? Mr Lander worked in restaurants for around five years before setting up his own. “People who own a place tend to have been successful working at another restaurant. Invariably, an investor is someone that the restaurateur has impressed on a professional level in another part of their career.” If you’re looking for money, Mr Hyman might be able to help. He assists his clients at CODE using the Enterprise Investment Scheme, which offer tax reliefs to individual investors.

Mr Morales had to be a bit more creative when he realised his idea for a Peruvian restaurant in London was an unproven one. “Nobody wanted to invest, no bank wanted to lend me money. But through testing at supperclubs and pop-ups, we gained real foodie fans who followed us. Once I sold my house in 2011, I was lucky enough to have some of our fans join me and help fund Ceviche.” If you do need a bank loan, and the idea is good, they can be surprisingly supportive. “If you say you have a great idea for a Mexican tapas place that you and your flatmate came up with – they’ll slam the door in your face,” says Mr Lander. “But if you go with a business plan and, crucially, show them the money put in by people who have had professional success or simply have lots of capital, then they will look to support it. From a bank’s point of view, a restaurant is not a massively risky investment because you have the asset in the lease and the licence of your site, which they look at kindly.”

05. FIND THE RIGHT SITE

Photograph courtesy of The Quality Chop House

“The competition for sites in London is ludicrous – this is by far one of the toughest hurdles in opening a restaurant,” says Mr Hyman. “You need to be forensic – 50 yards in the wrong direction on a street can make all the difference. Spend time pounding the pavements, go at difference times of the day and look at the sorts of people on the street.” However much research you do, a good location can present itself almost by accident. “With The Quality Chop House, we were just looking for a restaurant – not necessarily a listed Victorian dining room in Farringdon,” says Mr Lander, who highlights the importance of working well with what you do find. “When you try and do a specific type of food with no regard for the space, it’s a recipe for disaster. We moulded our offer to suit the building, the area and the regulars. And we’ve done that with all three of our restaurants.”

Mr Lander’s portfolio is representative of the three main routes restaurateurs tend to go down when searching for a location. “The Quality Chop House came with a lot of history and reputation which we didn’t want to alter,” he says. “Clipstone was an existing restaurant that we redid as our own with no nod to its past. Portland was a clothes showroom and we had to gut it and start from scratch.” There is no “correct” path to take. Purchasing a new restaurant brings the benefit of autonomy, and a new asset, but taking over an existing place with good facilities can present better value in the long run.

It can be tempting to assume that expansion of the like Mr Lander has overseen is the only way to make money in the restaurant industry. But this is not necessarily true. And, with rising food prices, expansion is becoming increasingly difficult. “Having one [restaurant] allows you to be very profitable,” says Mr Lander. “When you move to two or three, you are vulnerable because you have to protect that first one and it becomes complicated. When you open for the first time, you should devote your first year to being there the whole time. This keeps labour costs down and standards at the level you want.”

CODE’s Mr Hyman also stresses the importance of your first year as a restaurateur: “I don’t think a restaurant properly becomes itself until after 12 months of being open. This is an art, not a science.”