THE JOURNAL

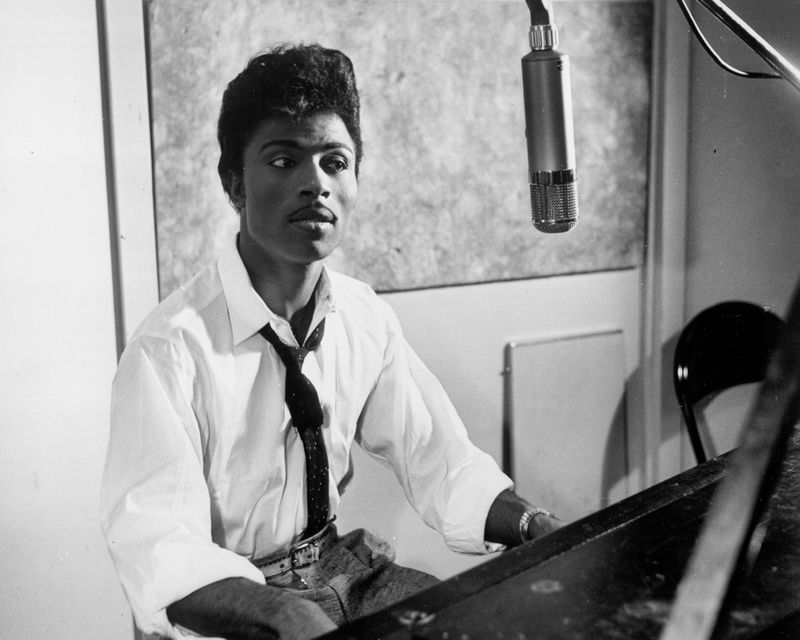

Little Richard in a recording studio, circa 1959. Photograph Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Over the course of his career, which spanned more than seven decades and several musical genres, and featured history-making moments and many personal trials and tragedies, Little Richard was always camera-ready. Ms Lisa Cortés’ new documentary, Little Richard: I Am Everything, shows just how. A wild ride through the star’s life, it also features the fashion he wore over those years. The self-described “architect of rock’n’roll” was ahead of his time in many ways. And one of those ways was knowing that his look should be as memorable as his sound.

His 1950s look – oversized quiff, immaculate panstick makeup, pencil-thin moustache and impeccable if oversized tailoring – shows how shrewd he was, from his early days. Richard signed his first record contract in 1951 and had a string of hits including “Tutti Frutti”, “Good Golly, Miss Molly” and “Lucille”. It was in this decade that he developed his classic look as seen here. Worn everywhere from the stage to television performances to photoshoots like this one from around 1959, the consistency ensured he was instantly recognisable. It endeared him to a new generation of young music fans, embracing a sound and look designed just for them. And just like his famous shriek, it fast-tracked the US – and the world – into the modern era.

Of course, the look didn’t come out of nowhere. Little Richard was born in 1932 and grew up as one of 12 children in Macon, Georgia. Effeminate from an early age – and with a slight deformity that gave him an unusual gait – he stuck out, and was subsequently thrown out by of the family home. Joining the tours of Black musicians sometimes called the Chitlin’ Circuit, he revelled in a culture that was more permissive to young queer people of colour, and their self-expression. During these early years, Richard was able to experiment with his appearance. He sometimes performed in drag, under the name of Princess LaVonne, or – accurately, thanks to his significant beauty – The Magnificent One.

For his trademark look, Richard absorbed influences from other performers in this scene and made them his own. He met Mr Billy Wright, an openly queer singer who had also performed in drag. Wright wore loud suits, sometimes with shoes in a matching colour and – crucially – a pompadour hairstyle. Esquerita, a singer Richard met at the bus station in Macon, further encouraged the take up of Richard’s hairstyle and pencil moustache. Writing for The Guardian in 2020, Mr Tavia Nyong’o quipped “the question of who wore the pompadour first will probably go for ever unanswered”. Crucially, however, none of this was purely imitation. As writer Ms Zandria Robinson says in Cortés’ documentary, “it was a case of witness – [they were] mirrors who come into your life to show you who you really are.”

Little Richard became a bona fide star in 1955, thanks to “Tutti Frutti”. It was a monster hit, selling a million copies and charting in the US and the UK. Crucially, his look of quiff, tailoring and moustache might have come from queer culture, but it actually helped him “pass” as he increasingly spent time in the mainstream spotlight.

“He gave the world flamboyant androgyny, which would become an essential part of rock’n’roll”

Ostensibly smart, respectable and polished, he could be seen to be following the example set by other Black musicians permitted in white spaces, including Mr Fats Domino, who wore a suit and tie. But the immaculate tailoring and flawless face were sacrificed to frenetic and energetic shows, which often saw one of his pant legs balanced on the top of his piano as he played. They ended with Richard drenched in sweat – an image that was, in the buttoned-up 1950s, highly subversive.

Subsequently, “Tutti Frutti” was covered by white singer Mr Pat Boone, who sung a stripped-down version on TV wearing a very un-rock’n’roll cardigan. Richard rightly saw this as what we would now call gatekeeping. He was permitted mainstream success, but only up to a certain point. Richard’s look – with hair a little too high, a face a little too perfect and tailoring designed to move in – was a crucial factor to this ring-fencing. “The white kids would have Pat Boone upon the dresser and me in the drawer because they liked my version better, but the families didn't want me because of the image that I was projecting,” he told The Washington Post in 1984.

Indeed, his look was central to why kids liked Richard. Speaking in Little Richard: I Am Everything, film director Mr John Waters talks about the impact that Richard had on him as a young person growing up in Baltimore. “The first songs that you love and your parents hate form the soundtrack of your life,” he says, adding that his signature pencil moustache is a “twisted tribute” to Little Richard.

Waters wasn’t the only one. Everyone from Mr James Brown to The Rolling Stones were inspired by him – Brown even began his career as a Richard impersonator. When Richard died in 2020 at the age of 87, guitarist Mr Steve Van Zandt said he gave the world “flamboyant androgyny, which would become an essential part of rock’n’roll”. A picture of him with The Beatles on tour of the UK in 1962 – when, as Richard says “nobody knew them but their mamas” – oozes star power. He’s the finished article, flanked by four soon-to-be-fab dorky teens.

As black and white turned to colour in the 1960s and 1970s, Richard leaned into queer identity more explicitly, with clothes that bent gender norms and appearances on stage that were unapologetically camp. Jumpsuits, capes, cropped tops and matching flares, sparkles and sequins supplanted the suits – the kind of outfits that, in 2023, would still stop traffic. Richard remained aware that what he wore had power. Following a storming performance by Ms Janis Joplin at the Atlantic City Pop Festival in 1969, he turned to his manager and said, “Bring me my mirrored suit”. Glittering from the stage, he once again stole the show.

Even if his trademark look had its roots in the underground queer culture of his formative years, and his celebratory outfits symbolised a sense of liberation, Richard grew up in a deeply religious household. His struggles with his sexuality were a theme across his life, one that flip-flopped from self-acceptance to denouncing the “gay lifestyle”. In 1995, he told Penthouse magazine, “I’ve been gay all my life and I know God is a God of love, not of hate.” But, by 2017, he said being gay was “unnatural”. This all came out in what he wore – ranging from the self-expression of jumpsuits and pompadours to the more typically heteronormative outfits of jeans, zip-up jackets and sunglasses.

Even with these struggles, Richard’s style no doubt changed the game for LGBTQ+ people in the public eye. The style legacy of the Magnificent One is only just being explored. Mr Billy Porter, speaking in Little Richard: I Am Everything, puts it like this: “as a Black queer man, the reason I show up and do anything I want is because of him”.

This documentary rightly places everyone from Mr David Bowie to Sir Elton John, Prince and Mr Harry Styles in his debt. Lil Nas X, an openly queer Black pop star who wears unapologetically bright tailoring and hairstyles that demand attention, might just be his rightful, magnificent, heir.