THE JOURNAL

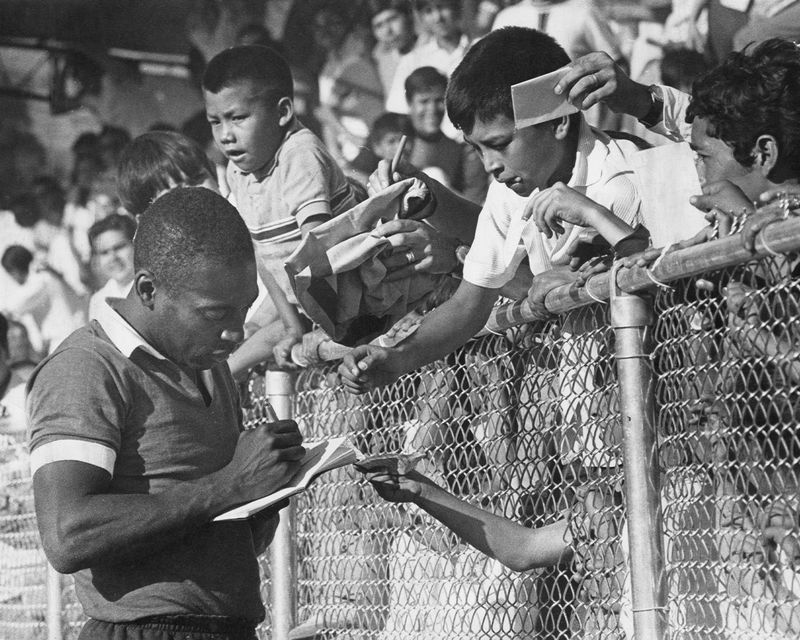

Pelé signing autographs for young fans during a training session for the World Cup, Mexico, 1 June 1970. Photograph by Getty Images

Sometime in the late 1960s, Ms Jan Myers lowered herself into the sewers of northwest London and crawled in the direction of Abbey Road Studios. There, from a secret subterranean vantage, she endeavoured to hear The Beatles record together for the last time. In another London odyssey straight out of Mr JG Ballard’s Crash, she cycled 20 miles to catch a glimpse of the Fab Four as they touched down at Heathrow Airport.

Myers – and fans like her – characterised hardcore fandom in the pre-internet epoch: to love something deeply meant you had to be prepared to get into a sewer for it. Old-fashioned devotion like this continues to burn brightly across the globe, with stories of outré acts of dedication filling our inboxes and news feeds weekly. Last year, a superfan of Ms Kim Kardashian had her hero’s signature tattooed across her hand, prompting the reality star to send her an affirmation worthy of Ms Kathy Bates’ homicidal Misery Chastain: “I’ll love you forever.”

As a full-tilt Radiohead obsessive myself, I joined a group in an alleyway near London’s Koko in the mid-2000s for a glimpse of the back of Mr Thom Yorke’s head, only to find myself in conversation with the band’s driver about Mr Jonny Greenwood’s guitar plectrums. After five hours of waiting and still no Yorke, the chill had nearly taken the tips of my fingers: I felt drained, cold, uncool, and all the while closer to something alive in me.

In the 1970s, fans started organising into small armies, and would follow their heroes around the world under aliases such as the “Deadheads” – the Grateful Dead’s cabal born from the San Franciscan psych-art scene. Still going strong in 1991, the Deadheads climbed a 2,000ft mountain to watch the band play in the foothills of Lake Tahoe, clinging on as their idols tore up the stage below.

All it meant to be a hardcore music fan in the 20th century was crystalised that night in the Sierra Nevada mountains. But today, in the wake of the internet, algorithms and social media, hero worship contains multitudes. For starters, the web is a unifier for people whose interests run so niche that they assumed they were alone in them. It’s also a way of centralising international fandoms separated by time zones and physical space.

These days, pop armies such as the Beyhive (Beyoncé’s infinitely ballooning base), the Navy (Rihanna’s), or the Directioners (One Direction’s) don’t have to risk mountain sickness to find each other. To locate your tribe and satiate your servitude, just type a few key words into the search engine of your choice and behold a vast allotment of memes, takes, and take-downs.

In 2018, Dr Rebecca Williams, a specialist in participatory cultures at the University of South Wales, published a paper exploring the world of Tumblr fan pages, arguing that they are exactly the kind of internet spaces that enhance the fan experience and encourage community-building. Using her favourite TV show _Hannibal _as a case study, she wrote how the peer-to-peer reblogging of Gifs, fanart and media from the series was more than just a way to connect with fellow fans and share theories in a completely anonymous environment.

Drawing on analysis from Mr Sigmund Freud, Williams claimed the feed content helped her to gently exit her mild addiction to the show after the final episode aired.** **“Tumblr seems to understand fan practices and behaviours in a way that other spaces online like Twitter and Instagram don’t,” she tells me.

For Williams, Tumblr’s format (a scroll of colourfully glitched fanart, quotes and trivia) has allowed fans to feel as though they are contributing to, and perhaps even expanding on, the creative legacy of their heroes. “There is a definite type of language and style of expression on Tumblr that makes it seem like a community even if people are discussing very different fandoms,” says Williams, who predicts a resurgence in the platform as users drift away from Twitter.

“Fans didn’t see their own harassing behaviour as harassment, or as problematic, because it was morally motivated”

The role of social media algorithms in directing people’s attention closer to their specific interests and those with opinions similar to their own is one of the great steps forward in fan culture. But it is also true that, unlike Jan Myers all those decades ago, you don’t have to crawl through dung to get close to your idols anymore. As the 1990s PR models that created safe buffers between fan and artist continue to lose relevance, celebrities promote their opinions and projects via Twitter and IG firsthand.

There are dangers that have been sparked by social media’s ability to efficiently rally fans into spaces that contain niche views, or platforms that allow unfiltered communications lines to their heroes. On the web, adoration can turn into mass mobilisation in a flash, and online armies have been known to share the private information of their foes or the famous in order to make a point or take a stand.

It was around two decades ago, when broadband made the internet a truly accessible commodity, that the word “stan” entered the popular lexicon. The notion of a celebrity devotee whose fandom bled into dangerous fixation wasn’t anything new, of course, but stan – a portmanteau of “stalker-fan” coined by the 2000 Eminem track – came to describe a freshly internet-driven strain of idol worship. Stanning, though mostly used light-heartedly online, could also signal the point at which a person’s fandom had drifted somewhere obsessive.

In June 2018, Ms Nicki Minaj’s army, the Barbz, started angrily tweeting at journalist Ms Wanna Thompson for suggesting that Minaj concentrate on more grown-up lyrical topics. When Minaj privately messaged her, Thompson posted a screenshot of the conversation to her 14k followers, and all digital hell broke loose. The Barbz got their hands on Thompson’s personal email address and mobile number, and sent a hurricane of abuse – some in the direction of her four year-old daughter.

As one Barb told Rolling Stone at the time: “It’s like a lion with their cubs. You don’t mess with the babies, and Nicki is our baby.” But it was The New York Times that summed up the incident best, describing the stanning as “one part dystopian sci-fi, and one part an everyday occurrence in pop-culture circles online”.

The Barbz debacle showed us that in the world of internet fan culture today, safety and personal privacy is up for grabs on both sides of the civilian-celebrity coin. Take it from Aja Romano, an author who explores internet fandoms across the decades. In 2003, a user they often shared internet space with on fansites hacked their private blog and leaked their birth-name – attaching, as they describe, their “real name to their fandom identity”. The incident – which they suspect was the reason they started writing about fandom culture rather than just participating in it – raised a flag about the crossovers in modern fandom culture with toxic online behaviours.

For Romano, the latest development in fandom folds into movements that have come to define and dominate the social media experience. For them, the mobilisation we saw in 2018 has become more politicised in fan culture communities, with less focus on the art or the object and more on codes of ethics – the logic being that if you feel that what you believe in is morally right, it’s OK to rally an attack.

“It’s an obvious manifestation of the phenomenon that internet culture researcher Alice Marwick has identified as ‘morally motivated networked harassment’,” Romano says. “Marwick studied numerous online communities, including several fandom communities, and across all of them the clear link was that once an internet social community felt morally justified, they were then able to justify any amount of harassment – even in cases where they claimed to be against harassment. They simply didn’t see their own harassing behaviour as harassment, or as problematic, because it was morally motivated.”

Zooming into this new trend, Romano witnessed BTS’s online popularity surge as the group’s fan base, “ARMY”, mobilised against Trump in the 2020 US election.

In a lengthy piece for NBC, Ms Kalhan Rosenblatt declared 2020 “The Year of The Stan”. From K-pop stans flooding out racist hashtags on Twitter to the radicalisation of a Ms Miley Cyrus tribute page, she explored how celebrity fans affected political discourse during the pandemic, and how these movements amounted to a turning point for global fan culture.

“There are overlaps and similarities in how some fans behave when supporting their fan objects (like threatening other groups of fans, or even individuals) and the broader toxic digital landscape,” Williams says. “We can see some links between some of the more toxic fan behaviours, not just from male fans, but female fans as well and the broader shifts towards an increase in trolling and negative types of behaviour.”

Like anything internet related, perspective can get lost in the noise. For Romano, it’s important to remember that while social media has brought a politicised muddiness into fan culture, it has also permanently emboldened it. In the pre-Twitter era, they recall, “many fans used to rigorously prioritise their version of ‘the fourth wall’. This was an invisible wall of secrecy that, basically, was the first rule of the fandom club (don’t talk about fandom), and kept fandom activities hidden from creators and actors who might be shocked by fan behaviour or fan creations.” Now, Romano says, fans are as free as they’ll ever be to let their flag fly, and join Jan Myers in the allegorical drains under Abbey Road.