THE JOURNAL

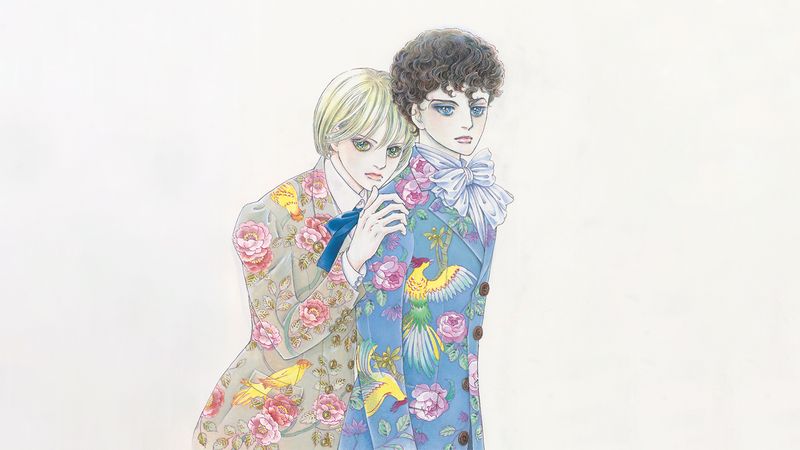

The Poe Clan by Ms Moto Hagio, 1972-1976. © Moto Hagio/SHOGAKUKAN IIN. Photograph courtesy of The British Museum

Picture the scene. Mickey Mouse is surfing. He looks determined, bent forward on his board as he clings to a rope dangling from an escaping speed boat. On board, a dastardly cloaked figure – the evil hypnotist, the Phantom Blot – empties the clip of a handgun at the pursuant mouse. BANG! BANG! BANG! In the face of this onslaught, Mickey remains stoic. “Ha! Ha!” he cries. “From now on, Mr Blot, I’m the forgotten man!”

Bewildering, yes, but Mr Floyd Gottfredson’s 1939 comic strip Mickey Mouse Outwits The Phantom Blot somehow feels right at home in the British Museum’s new exhibition, Manga マンガ. A love letter to Japanese cartoons and graphic novels, the exhibition traces the emergence of manga in 1200, through the 20th century and up until the present day. It’s a rich archive to draw from, with its fair share of surprises. If you thought Mr Gottfredson’s effort to have Mickey Mouse knocked off by a gun-toting Blot was strange, just wait until you reach Mr Hikaru Nakamura’s Saint Young Men, a manga that sees Jesus Christ enter a Catholic confessional to absolve himself of his jealousy of Father Christmas.

This breadth of imagination is characteristic of manga, an artistic medium whose output spans all ages and genres. To mark the opening of the new exhibition, we’ve picked out five gems from the museum’s exhibition.

Manga originated from a fight between rabbits and frogs. Maybe.

Contemporary manga emerged from serialised newspaper cartoon strips in the late 1800s, but the medium has deeper antecedents. While the form’s exact origins are contentious, the celebrated manga artist Mr Osamu Tezuka – 20th-century Japan’s answer to Mr Walt Disney – traced its roots back to Handscrolls Of Frolicking Animals (Chōjū giga), a 12th-century scroll said to have been created by the monk Kakuyū, also known as Toba Sōjō. Represented in the exhibition by a 16th-century reproduction, this delicately-inked scroll shows a wrestling match between frogs and rabbits, overseen by an umpire, whom happens to be a monkey. Contemporary manga’s use of simplification, exaggeration and abstraction, argued Mr Tezuka, can be traced back to this work.

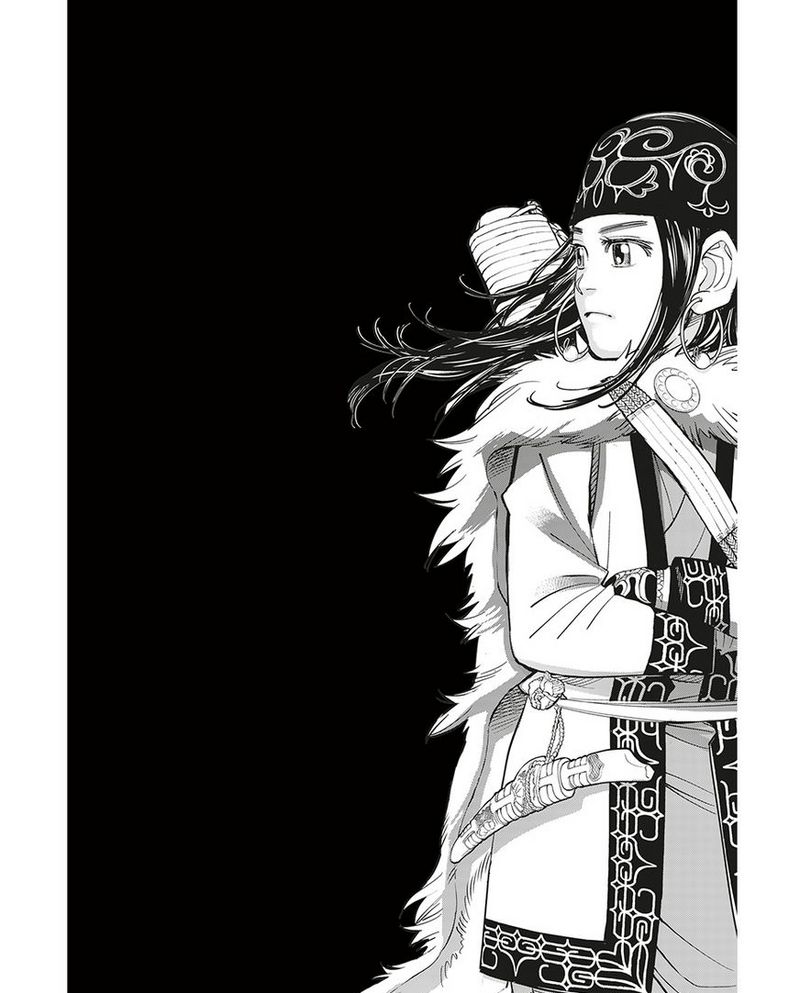

Golden Kamuy by Mr Satoru Noda, 2014 onwards. © Satoru Noda/SHUEISHA. Photograph courtesy of The British Museum

Manga is more than wide-eyed twinks and fighting androids

Big-eyed characters, frenetic action and speed lines as far as the eye can see: it’s easy to dismiss the visual tics of manga as caricature. Plenty fit this template, such as Mr Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball, or Mr Tezuka’s Mighty Atom – but the medium is far broader. Ms Moto Hagio’s The Willow Tree, the story of a young boy growing up without his mother, is a masterclass in stillness. Mr Gengoroh Tagame’s My Brother’s Husband, about discrimination and sexuality, has a hyper-masculine style. And Mr Junji Ito’s Uzumaki (Spiral), a horror story with excruciatingly detailed art that sees human bodies curled up in casques like Cumberland sausages, puts paid to the idea that all manga looks the same.

Manga means big business in the real world

In 2016, Japanese manga publishers enjoyed a revenue of $3bn and, as one might expect of an industry of this scale, the effects are far from limited to its own field. One of its more unusual manifestations is in the form of public service announcements. In 2017, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs used a manga character from Golgo 13 as the mascot in a security guidelines campaign for Japanese businesses abroad. Duke Togo, the handiwork of Mr Takao Saito, is a professional assassin, which made him a slightly aggressive poster boy for international trading. But perhaps the message was that Japanese industries really do mean business.

Manga is instructive

Not all manga is fantasy based. Much is solidly rooted in the everyday. Ms Fumi Yoshinaga’s What Did You Eat Yesterday?, for instance, is an example of gourmet manga, and sees Ms Yoshinaga use the story of partners Mr Shiro Kakei and Mr Kenji Yabuki to share recipes that she has created. “Rice cooked with the intention of making rice porridge is always more delicious than making porridge from pre-cooked rice,” notes Mr Yabuki.

Manga loves eroticism

As a family-friendly exhibition, Manga マンガ treads somewhat gingerly around the steamier side of its subject. A polite exhibition caption acknowledges that while manga covers a range of topics, “[A] large proportion is erotic. Some titles are sexually explicit.” For those hoping for a deep dive into shunga art and hentai imagery, Manga マンガ is not the exhibition for you (although the show catalogue provides some succour), but there are nonetheless fascinating portrayals of sexuality and relationships within the display. Ms Keiko Takemiya’s The Poem Of Wind And Trees (Kaze to Ki no Uta) arrived in the mid-1970s and shocked audiences with its portrayal of protagonists Gilbert Cocteau and Serge Battour entwined, naked in bed. Today, Ms Takemiya’s work is viewed as one of the cornerstones of “Boys Love” manga, a genre drawn by women that chronicles male romance for a predominantly female readership.