THE JOURNAL

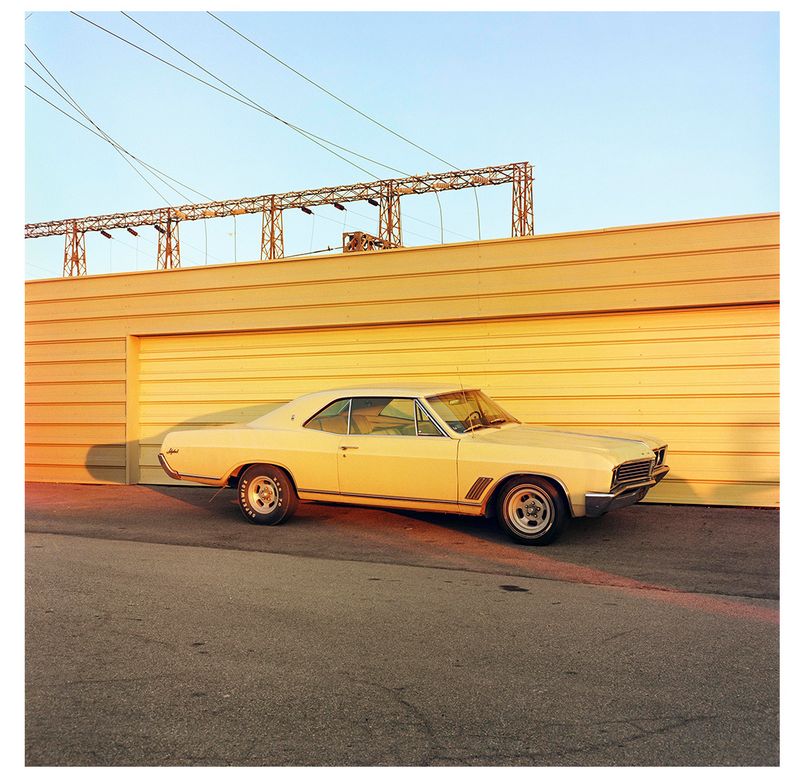

Untitled, c. 1977, by Mr William Eggleston. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner. © Eggleston Artistic Trust

“You know, William, colour is bullshit.”

It is one of those fortuitous moments in photographic history that Mr William Eggleston chose to ignore this piece of career advice. Having just begun his experiments with colour photography in the early 1970s, Mr Eggleston might have expected a little encouragement when he attended a party at which the great humanist photographer Mr Henri Cartier-Bresson was present: “You know, William…”

Today, Mr Eggleston is widely celebrated as the most influential artist in the elevation of colour photography as an art form, and a practitioner whose trailblazing work helped drive its acceptance by an art establishment reluctant to embrace its potential. A spot of luck, then, that Mr Eggleston had the self-confidence to reject Mr Cartier-Bresson’s assessment of the medium. Born in 1939 on a former cotton plantation in Memphis, Tennessee, he is said to have greeted the unwelcome advice with a degree of Southern civility. “I said, ‘Excuse me,’ and left the table,” he later recalled. “I thought it was the most polite thing to do.”

Sadly, Mr Cartier-Bresson’s party cattishness was not the only brickbat Mr Eggleston had to endure in the early stages of his career. His breakthrough self-titled 1976 exhibition at MoMA in New York was not the first time that the museum had exhibited colour photography, but it nevertheless became a lightning rod for the critical backlash against the medium. While the exhibition’s curator Mr John Szarkowski praised colour’s capacity to exist as “more than simply descriptive or decorative, and [instead assume] a central place in the definition of the picture’s content”, those who visited MoMA to see Mr Eggleston’s work were less convinced. “Perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly,” wrote The New York Times’ Mr Hilton Kramer. “[Mr Eggleston] likes trucks, cars, tricycles, unremarkable suburban houses and dreary landscapes, too, and he especially likes his family and friends, who may, for all I know, be wonderful people, but who appear in these pictures as dismal figures inhabiting a commonplace world of little visual interest.”

Untitled, c. 1977, by Mr William Eggleston. Courtesy Eggleston Artistic Trust and David Zwirner. © Eggleston Artistic Trust

While history has revealed Mr Kramer’s artistic judgment to be sorely lacking, his bare bones description of the content of Mr Eggleston’s work is essentially accurate, as a new exhibition of the artist’s work at London’s David Zwirner Gallery makes clear. 2¼ is a selection of square-format pigment prints, shot by Mr Eggleston in California and the American South around 1977. Saturated with colour and woozy with Southern lighting, the photographs leave the viewer in little doubt as to Mr Eggleston’s preferred subject matter. Cadillacs and cab trucks sit gleaming in empty car parks and side streets; knock-off Eames chairs perch by gas stations forecourts; tired store fronts are pebbledashed with rusting signs advertising “NEW AIR CONDITIONERS $89.95”; and a teenager with golden Californian hair and a candy-coloured tank top stares squarely at camera, seemingly a little bemused by the empty suburbia that sprawls behind her. The vivacity of the colours is intoxicating, but there is little doubt as to the feeling of urban decay that lurks behind the patina. It is no coincidence that the final image of 2¼ shows one of Mr Eggleston’s beloved roadsters junked at the side of a country road, its framework fire-bright with rust.

This sense of unease lurking beneath seductiveness is typical of Mr Eggleston’s work. The square format of the 2¼ photographs blurs the barriers between portrait and landscape, creating a parity across their subject matter. Mr Eggleston’s photographs of cars and small-town America become portraits of a place and its atmosphere, while his shots of people slip out of the realm of portraiture and into instead present their subjects as features of their environment. Washed in the same piercing colour, Mr Eggleston’s people and places blur together, reinforcing the role that each play in forging the other. One photograph shows a bust of Martin Luther King, positioned stoically above a bar advertised as “Closed on Tuesday”. Another depicts an African-American man stood on a patch of grass staring into the camera, his clothes a little ill-fitting and his expression obscured by a pair of large sunglasses. He seems tantalisingly out of reach. Knowing the history of civil rights in the American South at the time these photographs were taken, it is impossible not to wonder about what lies beneath the serenity of these images.

It is this sense of contradiction that ensures Mr Eggleston’s work remains relevant today and which ensures its validity as a portrait of the contemporary US. At a time when California has grown to become the fifth largest economy in the world at $2.7tn, with the riches of Silicon Valley presented as emblematic of the American dream, it has also become the state suffering the highest levels of poverty and which is home to roughly one third of the nation’s welfare recipients. The saturated, flat beauty of the artist’s photographs of California juxtapose against the sense of decay and emptiness that accompanies their subject matter in a manner that is all too telling. Mr Eggleston’s jet-age automobiles gleam in sparkling colour, as does the rust and cracked asphalt that make up the world they move through.