THE JOURNAL

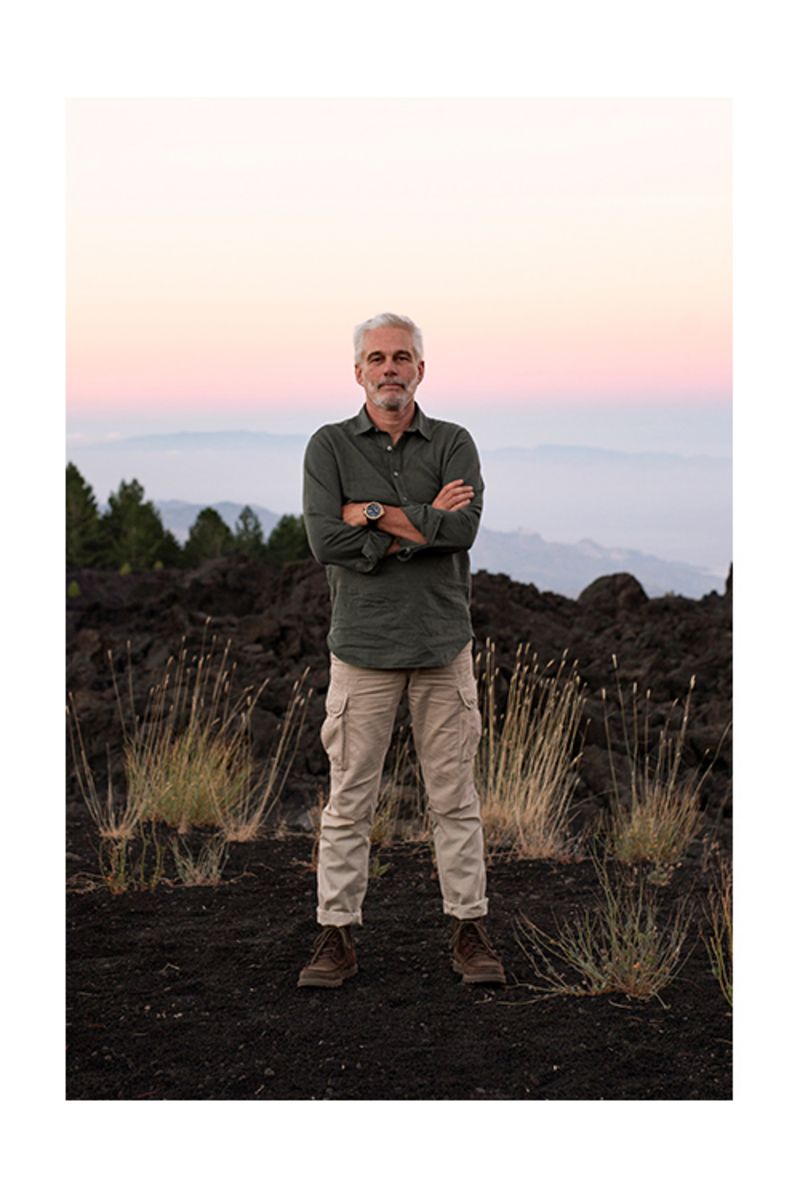

How a former Alpine climber reached the summit of natural winemaking on Mount Etna.

Mounted on the wall of a climate-controlled tasting room in Mr Frank Cornelissen’s Sicilian winery is a peculiar, three-dimensional map of Mount Etna. Instead of roads and settlements, it shows the successive volcanic flows that have shaped this dramatic landscape over the past half a million years, marking them as blotches of red, orange and yellow that streak down from the summit like spilled paint. “We’re right here,” says the Belgian, tapping his finger on a spot on the northern slope of the volcano, just beyond the reaches of its most recent eruption. “Every flow brings new mineral deposits, creates new microclimates. It’s what makes Etna such a unique place for viticulture.”

One of Sicily’s most celebrated winemakers, Mr Cornelissen is credited with helping to put Mount Etna on the viticultural map. His natural wines, produced with minimal intervention in the vineyard and an obsessive attention to detail in the cellar, are celebrated for their exuberance, their intensity and their lucid expression of place, a concept known in winemaking as “terroir”. They’ve found followers in the most unexpected of places, too. His Susucaru rosé briefly became one of the most searched-for wines in the world in 2016 after it was name-dropped in a Vice TV show by New York rapper Action Bronson.

What makes Mr Cornelissen’s success noteworthy isn’t just that it came in such a short period of time – he only arrived in Sicily at the turn of the millennium, having previously worked as a wine salesman and a distributor for a Japanese clothing brand. What’s more impressive is the fact that he had no prior experience of winemaking at all – just a passion for wine, a sense of adventure and a deep desire, as he puts it, to “touch the essence” of something. “My whole life has been a process of eliminating the unnecessary, of trimming everything back to its basics,” he says.

His interest in wine was sparked by his father, who encouraged him to start his own collection as a teenager and educated him on the single-vineyard grand vins of the Burgundy region in central France, which are among the most famous examples of terroir in all of winemaking. “My father’s curiosity drove my own,” says Mr Cornelissen. “After Burgundy, we explored Germany and Spain, then slowly became more interested in Italy. In the 1960s and 1970s, Italian wines were still relatively undiscovered, so we were driven not just by a love of wine but by the excitement of the unknown.”

My whole life has been a process of eliminating the unnecessary, of trimming everything back to its basics

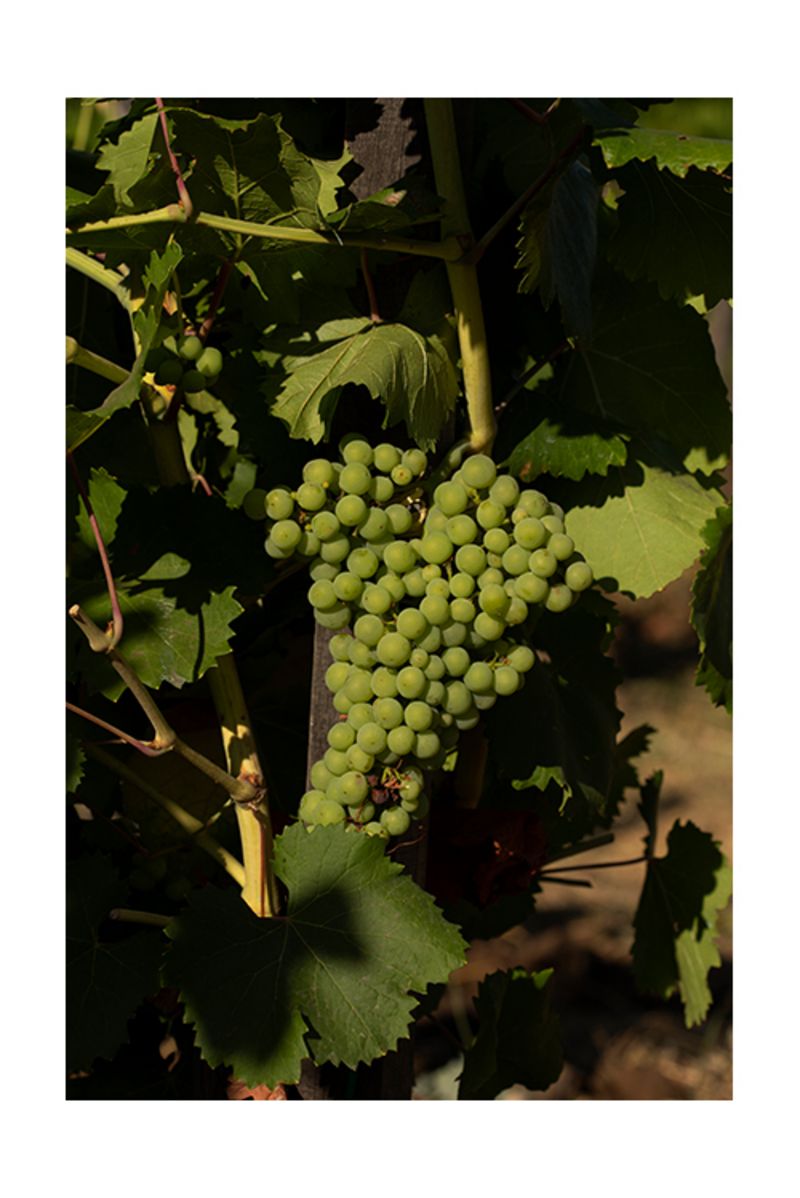

It was this pioneering spirit that eventually brought him to Mount Etna, an area still relatively untouched by commercial viticulture at the time. “Most people probably think I had a love affair with a Sicilian woman, but no,” he laughs. “I was just here for the wine.” It wasn’t just the romantic notion of cultivating grapes on Europe’s largest active volcano that attracted him. There was, as it happens, a quite specific reason that he chose Mount Etna: its volcanic soil offered him the opportunity to cultivate so-called “ungrafted” vines.

The ashy, mineral-rich soil produced when volcanic rock weathers to dust offers many benefits to the aspiring winemaker, but what attracted Mr Cornelissen is its resistance to phylloxera, a species of insect that was inadvertently introduced from the Americas and, in the 19th century, went on to devastate the great majority of Europe’s vineyards. The industry only survived thanks to an ingenious piece of botanical science. Native vines were grafted onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstock, creating the hybrid grape varieties used in European viticulture today. As for the vineyards that survived this infestation without the need for grafting, they’re now rare enough to be considered something of a holy grail to winemakers.

Mr Cornelissen’s wife paints the label on each individual bottle of Magma by hand

Mr Cornelissen’s quest for the perfect vineyard site had already taken him to Mount Vesuvius and Mount Vulture, two volcanoes in the south of mainland Italy. But there was something special about Etna. “It wasn’t just the volcanic soil, but the climate, the harsh winters, the stone walls, the right winds… it was all here,” he says. And, because there was so little in the way of commercial winemaking infrastructure, he was free to let his instincts guide him. “I didn’t want to follow an example,” he says. “I wanted to start on my own. I’m very much an individualist.”

When he tasted his first bottle from the slopes of the volcano, he knew he‘d landed in the right place. “It was nothing fancy,” he remembers. “A small producer – it didn’t even have a label. But it had the right tannins, it had structure and it had incredible finesse. It was just an unbelievable wine.” Inspired by this revelatory bottle, he purchased his first vineyard, Barbabecchi, a small site just over 900 metres above sea level. Once abandoned and left dormant, it now produces grapes for his most celebrated wine: Magma.

Most people probably think I had a love affair with a Sicilian woman, but no, I was just here for the wine

Magma is Mr Cornelissen’s grand vin, a single-estate wine in the Burgundian style. A single bottle of its newest vintage sells for around €220 – that is, if you can get your hands on one. With yields of just half a kilo per vine, Magma is in extremely limited supply. “Vines produce less fruit as they get older,” Mr Cornelissen explains, “and these are the oldest vines we have. It’s pure ungrafted nerello mascalese, planted before WWI.”

The name Magma is such a perfect encapsulation of Mr Cornelissen’s philosophy as a winemaker – he describes wine as “liquid rock” – that he was surprised at first that it hadn’t already been claimed. If he’d waited a while longer, perhaps it might have been. In the two decades since he arrived in Sicily, winemaking on Mount Etna has exploded, attracting investment from major players in the Italian wine market. Two years ago, Mr Angelo Gaja – perhaps the most influential winemaker in Italy – purchased 21 hectares on the volcano's south-eastern slopes.

It’s not just the area that has evolved; Mr Cornelissen’s wines have, too. Once a standard-bearer for the more extreme tendencies of natural wine movement, which espouses a zero-intervention attitude to winemaking, he has mellowed with age and experience. “When I started, my cultivation philosophy was to not touch the soil at all,” he says, echoing the philosophy of another natural wine superstar, Mr Hirotake Ooka. He still believes in letting nature take its course in the vineyard, but once the grapes have left the vine, he now assumes full control, running his winery with absolute precision and care.

He compares this approach to winemaking with another one of his passions: Alpine climbing. “Every harvest is a different climb. And you have one goal, which is to reach the summit without falling.” Adding sulfites to wine, he says, is the equivalent of drilling into the wall and ascending with the help of a belay. Natural winemaking in its purest form is more akin to free-soloing to the top in the style of Mr Alex Honnold. “The thing you do not want to control is Mother Nature,” he says. “The secret to reaching the top is to be so well-prepared, so physically fit, so strong in your fingers and in your mind that you can climb with minimum risk. It’s the same with wine. Preparation in the cellar is everything.”

All the preparation in the world can’t prevent the occasional mistake, but Mr Cornelissen welcomes them. “I always taste my failures. I still believe it’s much more interesting to make errors. My wines over the past 15 years have shown a constant evolution of my vision, my drive for perfection.” For that reason, he says, his best wine will always be his next one.

My wines over the past 15 years have shown a constant evolution of my vision, my drive for perfection

Mr Frank Cornelissen and his family