THE JOURNAL

Black Ivy: How Civil Rights Were Redefined Through The Culture Of American Prep

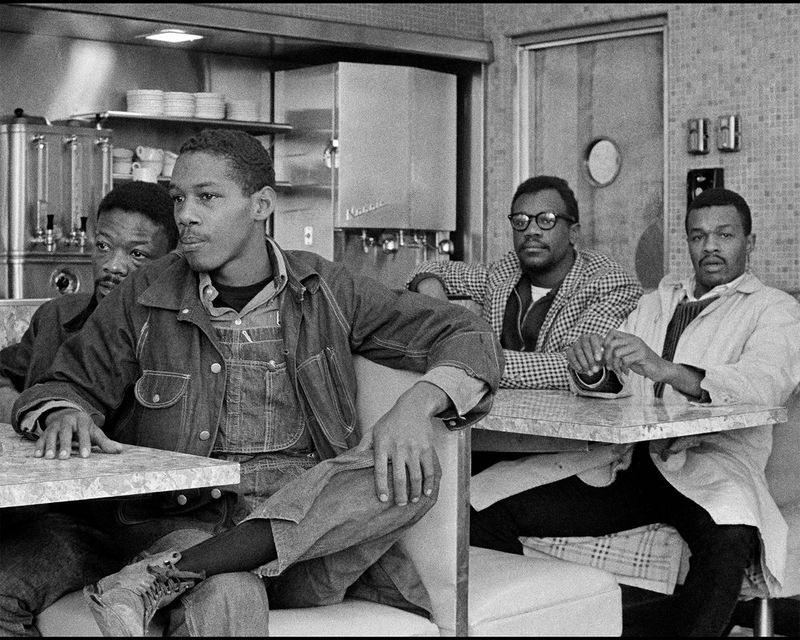

Messrs Courtland Cox, Marion Barry and other SNCC campaigners at a sit-in in Atlanta, Georgia, 1963. Photograph by Mr Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos

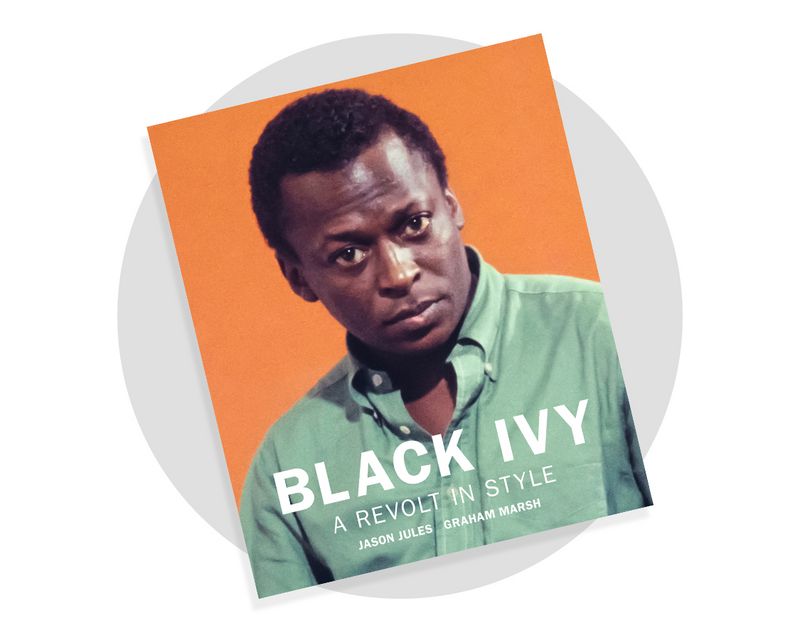

“Style is about the freedom to be oneself, to authentically express oneself and, in doing so, reject limitations imposed by others,” writes Mr Jason Jules in his book Black Ivy: A Revolt In Style. Produced during a recent sojourn in Paraguay, alongside co-author Mr Graham Marsh, it is a beautifully crafted study of the US during the 1950s and 1960s, a period when young black men adopted the uniform of the college-educated elite and used it to challenge perceptions – and prejudices – of African-Americans’ place in society.

“It feels like I’ve always had the idea,” says Jules of the book’s genesis from his sometime home in South America. “I always felt really strongly about the fact that there was a misinterpretation of how black style related to the Ivy look. From a very young age, I was committed to this look for aesthetic reasons, if nothing else, but somehow it seemed to trigger a lot of people. And it made me curious as to why it seemed like the natural thing for me to wear, but seemed unnatural to other people.”

For Jules, the framework of the book came with the realisation that “the period of time where Ivy style was at its peak completely tied in with the civil rights movement. And as I looked a bit more, I realised that a lot, if not all, of the civil rights activists were adopting this style.”

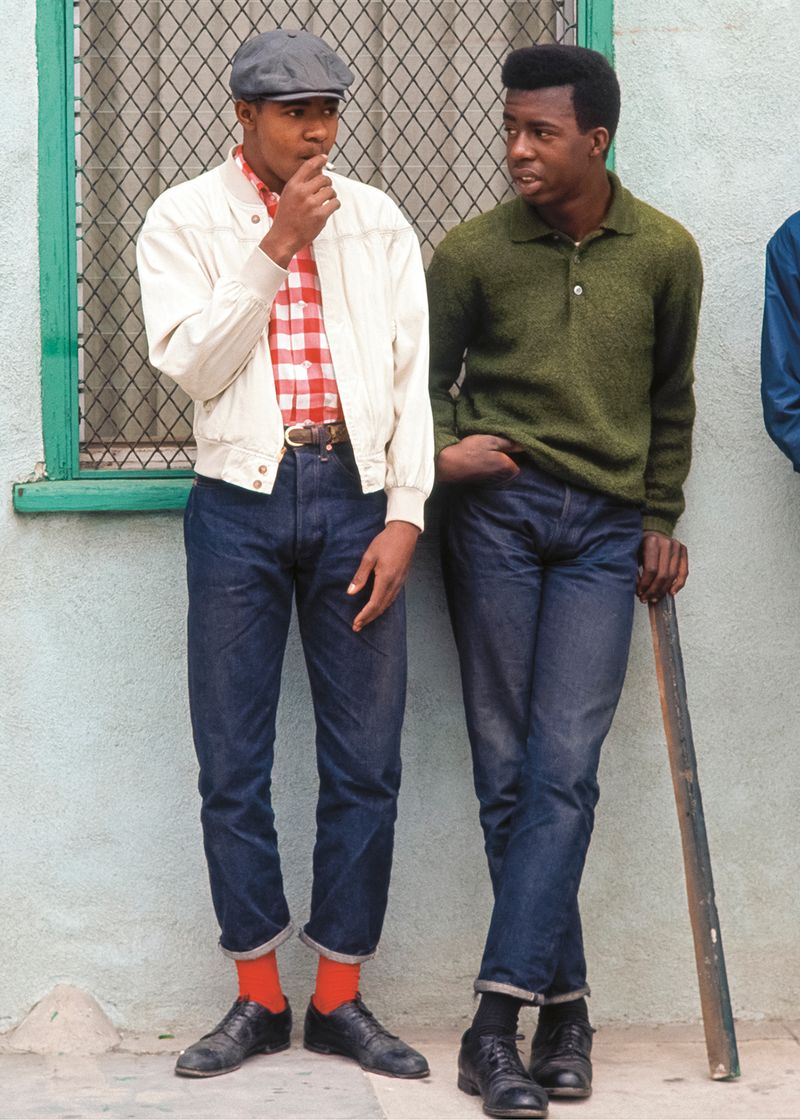

The book details how a swathe of African-Americans – from high-profile luminaries, such as trumpeter Mr Miles Davis and basketball player Mr Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, to the nameless citizens captured by Life photographer Mr Bill Ray in the aftermath of the Watts Riots – took the fashion associated with the most reactionary end of white society, deconstructed it and made it their own. On a superficial level, this created a style guide that remains timeless in its appeal and has informed everything from Mr Virgil Abloh’s work at Louis Vuitton to the relaxed prep of high-street retailers such as Gap and J.Crew.

On a deeper level, it is a defining example of how clothes are never just clothes and how the way one chooses to dress is freighted with significance, power and meaning. “The urge to wear these clothes was in no small part born of the desire to demonstrate that equality, which had been so fiercely denied them in other ways,” writes Jules in the book. “Making society treat them differently meant making the mainstream see them differently first. And they did.”

During this time, as the book illustrates, black menswear carried out “a kind of sartorial power grab”, proffering a smarter, slicker and more beautifully curated image than its upper-class white counterpart and presenting racists “with an overwhelming cognitive dissonance, upending the firmly held belief that black people were to present themselves as underlings”.

“Behind the purely aesthetic stylistic thing is this idea that we’re all responsible, we’re all supporting each other. This is how we’re showing our unity”

There is a long, proud history of outsider groups adopting and subverting the signs and labels of those who would exclude them. During the first mod wave in the UK, white working-class men couched themselves in the styles and affectations of the American, French and Italian avant-garde. The ballroom scene of New York in the mid to late 1980s allowed heavily marginalised dancers to rework the tropes of elitist culture, from business suits to Vogue editorials. In the earliest days of UK garage, a predominantly black working-class London audience adopted the labels, libations and cars of moneyed continental Europeans.

“Wearing something sharper and, in particular, something that was unintended for you in the UK is based on your social situation and standing,” says subculture photographer Mr Ewen Spencer, who came of age in the north of England’s mod revival scene and was one of the first photographers to document the roots of UK garage. “Picking up on expensive Italian or French garms was not only an act of escapism for us, but an acknowledgement to others in your locality that demonstrated your tastes and, in some ways, your aspirations.”

Echoing Jules’ appraisal of the black Ivy movement, he sums up this style as embodying “grace under pressure, clean living against the odds”. “This was a really considered movement, you know?” says Jules of its popularity with ordinary people at the time. “It kind of went top-down and back up again.”

Two young men in Watts, Los Angeles, California, July 1966. Photograph Mr Bill Ray/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock. Courtesy of Reel Art Press

The book comes at a particularly apposite time, as multiple figures are breaking down the barriers that define “permissible” black style, while considering how the period documented by Jules – with its heady mix of aesthetics, politics, aspiration and intellect – can provide a toolkit for navigating the modern age. Abloh’s AW21 presentation for Louis Vuitton, Ebonics / Snake Oil / The Black Box / Mirror, Mirror, referenced black Ivy mainstay Mr James Baldwin’s 1953 essay on black identity, Stranger In The Village.

Mr Tremaine Emory’s collaboration with Champion earlier this year used classic Ivy League tropes of madras fabrics and letterman jackets. Designers from Mr Nicholas Daley to Labrum London are deconstructing Savile Row-level tailoring and workwear and refashioning it with black diaspora stories in profound ways. And across American cities, flash mobs of exquisitely tailored black men are meeting up for impromptu symposiums-cum-catwalks (look up @blackmenswear on Instagram), upending preconceptions of what black urban life is.

“They’ll also have debates and break-off groups to talk,” says Jules. “And so behind the purely aesthetic stylistic thing is this idea that we’re all responsible, we’re all supporting each other, we’re all aware that presentation and image is important and community’s important and this is how we’re showing it. This is how we’re showing our unity.”

“Freedom and liberation come from defining or determining how you look based upon your own terms, your own aesthetic, your own worldview”

Black Ivy captures a period when clothes were far more than just fashion and shows how style can be part of a response to challenging times. “We are definitely in a period that we might characterise as a black cultural flourishing,” says writer and curator Mr Ekow Eshun. “I think the work that’s being done by creative figures in lots of areas is absolutely to do with a crossover between style, legacies and histories of visual culture, politics, identity – all of these things are bound up together.”

Eshun cites designers Ms Grace Wales Bonner and Ms Bianca Saunders, photographers Mr Tyler Mitchell and Ms Liz Johnson Artur, actress Ms Michaela Coel, musician Serpentwithfeet and singer Blood Orange as vanguards of this movement. “They’re all talking about similar territory in one way or another, where style is considered as an aspect of a cultural politics. What you find in all of those figures is this absolute confidence and desire to assert and self-fashion. To recognise that freedom and liberation come from defining or determining how you look based upon your own terms, your own aesthetic, your own worldview. And that’s not just a superficial thing of appearance; that is quite a deep-lying thing about place and the mark you want to make in the world.”

The black Ivy era showed how style could be deployed as an intrinsic part of a radical political, intellectual movement and could fortify a person’s identity when they needed it the most. And that noble idea’s moment has come again.