THE JOURNAL

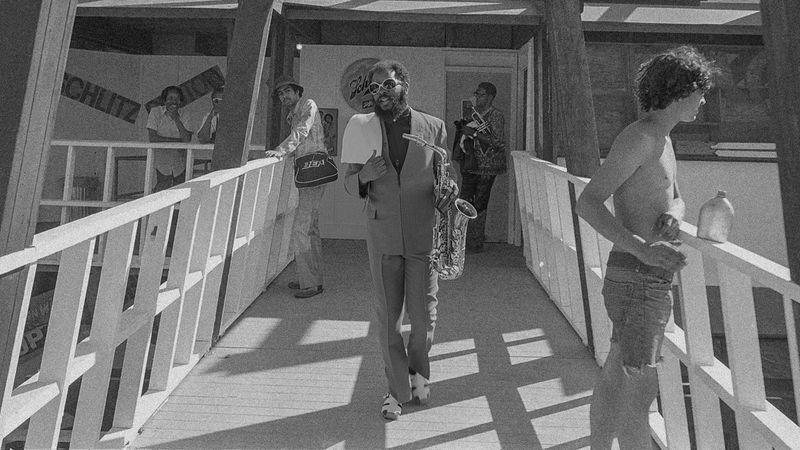

Mr Ornette Coleman at The Newport Jazz Festival, Rhode Island, 1971. Photograph © Mr James M. Mannas Jr/TT Griffith Archives

In 1961, saxophonist Mr Ornette Coleman released an album entitled Free Jazz, thus coining a genre based around improvisation. To visually represent the sound, Coleman’s album cover featured a reproduction of Mr Jackson Pollock’s 1954 painting, “White Light”. Like the music, it’s messy, wild, passionate and bright. Coleman and Pollock alike exploded their respective artforms, using no new tools other than the vast galaxies of their imaginations.

A decade and many albums later, Coleman’s renegade approach to jazz had moved from outlier to mainstream. He started his career promising the future with an album entitled The Shape Of Jazz To Come, and he made good on that promise. As his groups mined the reaches of jazz’s structures, others caught on, and free jazz became the genre’s signature sound in the 1960s, which many artists far surpassing Coleman in blaring sonics.

Instead of one-upping their din, Coleman began to explore other sounds, adding harmony to his signature dissonance. He certainly never abandoned free jazz, but he seemed to temper his approach, using inharmoniousness as part of a wide palette of sounds, rather than as the bedrock of his playing.

Mr Ornette Coleman performs at The Newport Jazz Festival, Rhode Island, 1971. Photograph by Mr David Redfern/Getty

When he performed at the Newport Jazz Festival in summer of 1971, he was on the eve of releasing an album of radiant energy, Science Fiction. Some songs are scattered, and some seem to predict disco, with the funky vocals of singer Ms Asha Puthli. That album cover features not a painting but a photograph, a time lapse capture of a sunset over time. There’s a rainbow in the background, and the sky drips red.

As was typical for a jazz musician of the time, Coleman often dressed in a suit. In his later years, there was no hiding his immense love of pizzazz in clothing, regularly wearing bold patterned jackets. But he was still beginning to push boundaries at the time of the Newport festival in early July. While the members of the band eschewed anything so staid as a jacket, Coleman, as the leader, appeared to have some fealty to formality onstage. Remaining playful, though, he wore a watermelon red suit, the trousers pressed pristinely, a crease running straight down his leg. He looks devastatingly cool.

It seems like a comical suggestion that anyone other than a singular musician should go anywhere wearing a red suit. What looks like genius experimentalism on one man may look like a try-hard disaster on another. How many times do you need to dress like you are centre stage before thousands of people?

But it’s the spirit of Coleman in the red suit that seems so crucial a lesson, a play on how to swerve expectations, not deny them outright. It may be bold, but it’s still a suit, a look that simultaneously denies the rules while still officially ticking the boxes. In many ways, it’s a lot easier to ignore custom than it is to toe the line of bucking it.

That’s what makes Coleman – and Pollock, too – such an important bridge between the outer space free for all of music that continued to open up in his lifetime, and the more straight ahead legacy of the music before him. He could play a solo of such devastating beauty that it would break your heart. Or he could pick up the violin, an instrument he was not much of an expert in, and wring emotion from it, if not exactly linear sound.

In his career, he played with everyone from Mr Jerry Garcia to Ms Yoko Ono to Mr Louis Armstrong, happily shapeshifting along the way. That was his superpower. Sometimes you lean into the red, and sometimes you lean into the suit.