THE JOURNAL

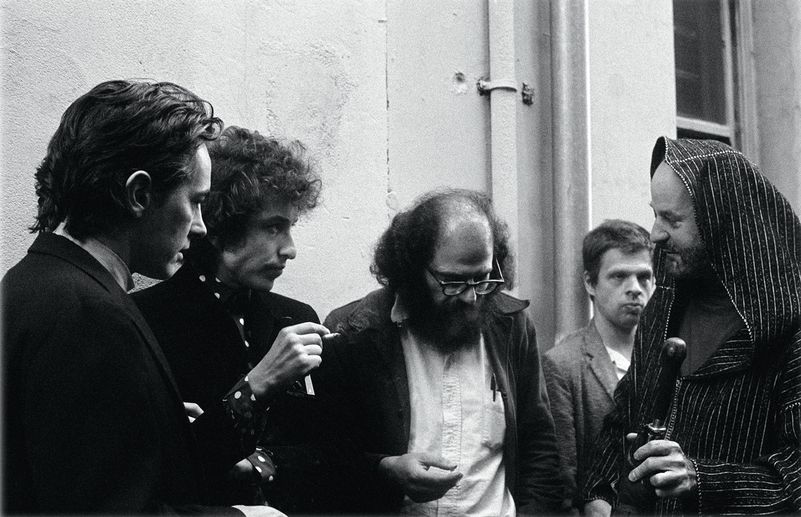

From left: Messrs Michael McClure, Bob Dylan, Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti in the alley behind City Lights, 1965 © 2015 Dale Smith, all rights reserved

At 96, Mr Lawrence Ferlinghetti, founder of City Lights, is a bridge between San Francisco’s Boho past and its tech future.

In the early 1960s, the fireflies began to disappear from Italy. Industrial pollution of the air and water had killed them. It was the moment of Italy’s fall, wrote the director and poet, Mr Pier Paolo Pasolini, when the country’s pre-industrial values were finally lost to a faceless modernity. The San Franciscan poet, bookseller and icon, Mr Lawrence Ferlinghetti, was affected enough by Mr Pasolini’s image of the dying fireflies that he has used it in his recent poetry to depict a similar process he sees underway in America. It is a loss of an anarchist spirit he has carried into everything he has done, from his poetry and painting to founding City Lights – a bookseller and publisher, wedged into a corner of San Francisco’s Columbus Avenue for more than 60 years.

He has experienced that loss particularly in his hometown – once the magnet for the Beat poets and the counterculture, now the hub of a technology industry with little sympathy for the past. He no longer sees the best minds of a new generation discussing revolution in cafés thick with pot smoke, but talking seed investment rounds in the glossy but prim conformity of Blue Bottle coffee. “You see everyone in cafés on their computers,” he said in the last interview he gave, in 2012, when he was a spry 93. “The feeling today is total materialism. Today is just as Ginsberg predicted [in his 1955 poem Howl]: Moloch has taken over.”

Ginsberg, of course, is Mr Allen Ginsberg, whom Mr Ferlinghetti befriended, and whose work he edited and published. “Moloch” was Mr Ginsberg’s shorthand for capitalism run amok. In 1957, Mr Ferlinghetti stood trial for publishing Mr Ginsberg’s poem Howl, on the grounds that it was obscene. Fortunately the judge found that the work’s social significance outweighed the colour of its language, and acquitted him. Not that Mr Ferlinghetti seemed too bothered. He said he did not mind the prospect of a few months in jail, as it would allow him plenty of time to read.

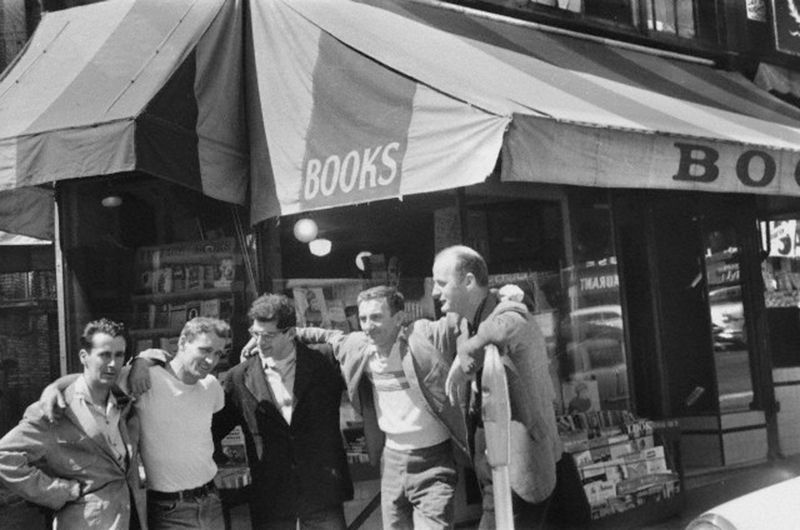

From left: Messrs Bob Donlin, Neal Cassady, Ginsberg, Robert LaVinge and Ferlinghetti outside City Lights, San Francisco, California, 1956 Allen Ginsberg/ Corbis

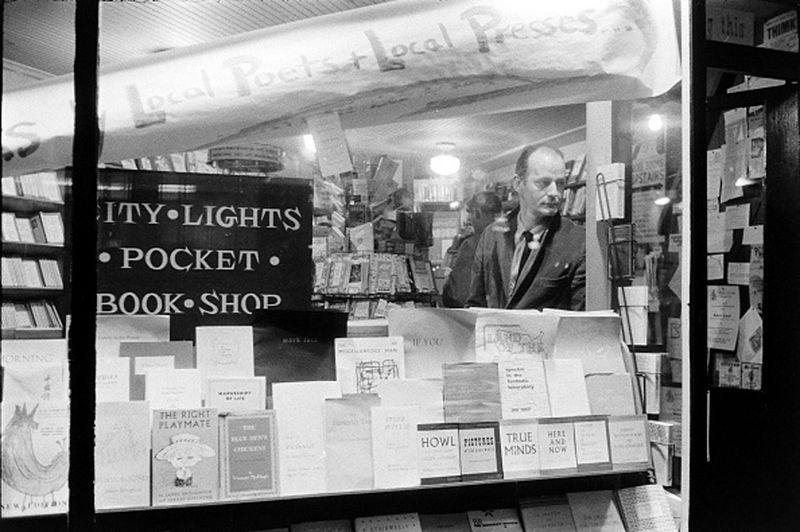

It seems quaint today to think of a bookstore as the cornerstone of a community, let alone a revolutionary one. But City Lights was just that. Its origins speak of another, very different location from the one we know today. This was the post-WWII San Francisco, coursing with recent European immigrants and young men and women who felt shut out of the great cities out East. The story goes that Mr Ferlinghetti, who had moved to San Francisco from New York in 1951, was driving home from his painting studio one day in 1953, when he saw a guy putting up a sign. He stopped his car and walked over to the man to ask him what he was doing. “I’m starting a paperback bookstore, but I don’t have any money,” said the man. “I’ve got $500.” Mr Ferlinghetti said he had $500 too. The man hanging the sign was Mr Peter Martin, a sociology teacher who was publishing a literary magazine called City Lights. They shook hands and a few weeks later opened the City Lights Pocket Bookshop to sell high-quality paperbacks, different from the cheap paperbacks then sold at newsstands.

It quickly emerged as a gathering place for the Beats. They would assemble across the alley at a rackety saloon, Vesuvio café: Mr Jack Kerouac in work clothes – cotton shirts and chinos, military jackets and work boots; Mr Ginsberg with his horn-rimmed glasses and wild beard. They may not have cared for fashion, but their look was taken up by Messrs Bob Dylan, James Dean and Andy Warhol, and can be seen today in the tailored work clothes worn by Brooklyn hipsters.

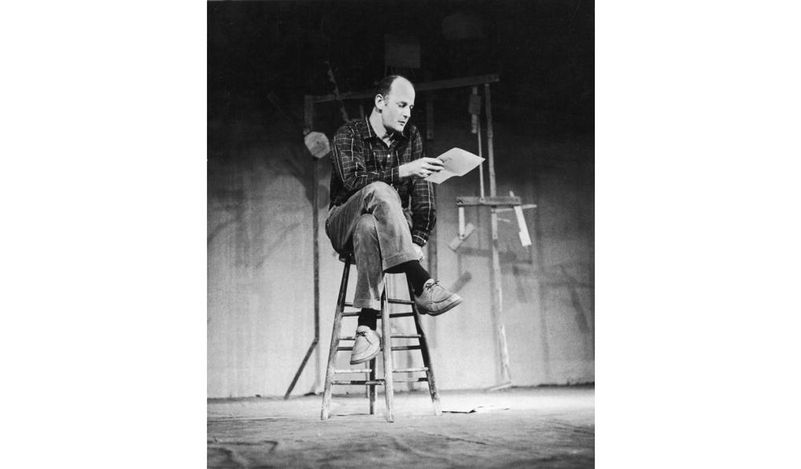

Mr Ferlinghetti reads from his poetry collection A Coney Island of the Mind at Living Theatre, New York, 1959 Fred W McDarrah/ Getty Images

Mr Ferlinghetti has always adhered to Mr Gustave Flaubert’s advice that artists should be bourgeois and orderly in their private lives, so that they can be “violent and original” in their work. As a publisher, painter and poet, he has been the epitome of the radical Bohemian – an earring in his right ear, a French beret or bowler hat tilted back on his head. He put on beads, danced at The Filmore and was there for the 1968 Summer of Love. Yet he had the discipline to produce volume after volume of poetry, including A Coney Island of the Mind, one of the bestselling books of poetry ever published. He could manage his business well enough to avoid having to apply for government funding for the arts, because that would have meant cooperating with a system he had accused of killing through war.

He has been a Fidelista in Cuba, a Zapatista in Mexico and in the 1980s travelled to Nicaragua to hang with the Sandinistas (a hat trick of South American radical leftism). But whenever he was in town, he was home by 6pm every night for dinner with his family. When Mr Kerouac needed a place to dry out, he borrowed Mr Ferlinghetti’s cabin in Big Sur. But Mr Ferlinghetti’s wife, Ms Selden Kirby-Smith – the granddaughter of a Southern Civil War general and daughter of a doctor – made sure that the worst of the Beats’ drinking and drug-taking was kept far from their home. Which may explain why at 96, Mr Ferlinghetti is still working, producing paintings and poems at a rate that would shame artists a third of his age.

Mr Ferlinghetti at City Lights book shop, San Francisco, California, 1957 Nat Farbman/ Getty Images

Like his idol, Mr Walt Whitman, Mr Ferlinghetti considers himself an optimist about America, but, in one of his latest works of poetry Time of Useful Consciousness (2012), he refers to the time a pilot has after his oxygen has depleted, before he passes out. America still has time – but not much, he implies – to reverse the effects of ecological, industrial and cultural damage. He cannot yet say, as Mr Pasolini did of Italy, that the fireflies have gone. But he poses it as a question: “Are there not still fireflies/ Are there not still four-leaf clovers/ Is not our land still beautiful.” The answer, he leaves up to us.