THE JOURNAL

Mr André Aciman lives in a spacious, minimally decorated seventh-floor apartment overlooking Morningside Park on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. An on-and-off resident of the city for 50 years, Mr Aciman has inhabited this apartment with his wife for 32 of them, raising three sons. And yet, Mr Aciman is reluctant to call the apartment, this city, or even the US, home. Any dedicated reader of this affable 68-year-old writer will recognise his fraught relationship with roots, place and permanence from his books. Mr Aciman’s astonishingly lush 1994 memoir Out Of Egypt tells the story of his family’s prosperity in Alexandria before eventually leaving, following the country’s exodus and expulsion of the Jewish population. In 1965, Mr Aciman’s father moved to Paris, while he, his mother and brother became refugees in Rome. In 1968, the family reunited in New York City, but those painful and provocative years of dislocation and itinerancy left a mark. His passion for books took shape in Rome, and when asked in what tradition he feels he is writing and living, he’ll say he’s “Mediterranean” and leave it at that. Mediterranean certainly does explain the sumptuousness of his prose on the subject of bodies and sensory pleasures.

It is safe to say that Mr Aciman is our best living writer on the subject of desire – on the sparks that fly between two people who happen to sit across from each other in a restaurant or, say, share a house for a summer on the Italian sea. In 2007, Mr Aciman published Call Me By Your Name and it immediately became a treasured tome among gay men for its honest, graphic, supremely loving and empathetic portrait of two young men swept up by desire. When, 10 years later, Italian director Mr Luca Guadagnino turned it into a film starring Messrs Timothée Chalamet and Armie Hammer, this intimate pastoral romance fire-crackered into what might now possibly be regarded as the most canonical gay romance in literature and cinema.

This month, Mr Aciman returns to the evolving story of Elio and Oliver (and Elio’s father, Sami), in the powerful follow-up novel, Find Me. Readers hoping for a fling-y seaside riff on Call Me By Your Name will instead find more turbulent and decidedly older characters – wiser, yes, but no less impassioned. Find Me hops from Rome to Paris to New York to Alexandria, each city with a potent memory lodged somewhere in a wall, a corner, a window, or a street. Befitting his rakish cosmopolitanism, Mr Aciman triumphs in characters who become unmoored, who break free of taboos and constraints to run headlong toward passion no matter the costs. In fact, Find Me is such an overt, unapologetic celebration of living, flirting, remembering, and loving, it’s almost jarring to read in such a cynical, exasperated age. Earlier this month, I stopped by Mr Aciman’s apartment to talk about revisiting his classic lovers and why he isn’t afraid of sex scenes.

___

You’ve been in New York for more than 50 years. Do you consider it home?

No. I live here. I like coming back here when I’m abroad. But is this home? Am I American? Yes, I’m an American citizen. But the real question about home is, where do you want to be buried? Even though you’re dead and won’t know the difference, that answer means something.

___

Where do you want to be buried?

I don’t know! [laughs] I know where I fantasise about being buried: in the Roman cemetery, Cimitero Acattolico. But I think you have to die there. You can’t have your body transported. But it’s a beautiful cemetery, maybe the most peaceful spot on Earth.

___

What is it about Italy that conjures so much romance in the foreign imagination, particularly with writers? Why is that country the backdrop for so many of our fantasies?

If I’m going to write a sexy story between two fledglings with beautiful bodies that aren’t wearing many clothes, where am I going to set it? Turkey? That doesn’t work for me. Italy comes very naturally. I know the country, the beaches, the little towns. I can let my imagination roam from one place to another. Italy automatically suffuses a story with the pleasures of being alive: sunlight, beaches, fruit, food, flesh. For example, when you look at Italians, they all have beautiful tans in the summer. They have such good skin. It glimmers. I think it’s because they don’t remove the oil on their skin. The rest of us soap ourselves to death. I’m just as guilty. I take two showers a day – sometimes three on a very hot day.

___

Why are you taking three showers a day?

I find it’s a good way to punctuate the day. Some people do that with drinks – and I do, too. But a shower can mean, OK, now we’re moving into evening.

___

You moved to Italy at the age of 14 with your mother and brother after your family left Egypt. Is some of the romance for Italy wrapped up in those early memories?

Those years were important for me because that’s where I really began to read. But I hated Rome when I first landed there. I wanted to be in Paris. We spoke French at home, so Paris was a natural extension of life in Egypt. Instead, I was in Rome, in a poor neighbourhood, it wasn’t nice. The Italian language itself offended me. So, every week, on Friday or Saturday, I would go to an American/English bookshop and buy a book. I had just enough pocket money to buy that book, and I would go home and basically read the book for the rest of the week. Eventually, though, Rome seduces you. I was a teenager roaming the city on those Fridays or Saturdays, horny as hell [laughs], although I never got laid. And I’d go to that bookshop and buy a book, which maybe was better than getting laid. It has something to do with the libido. The intellectual libido, the aesthetic libido. I have no idea, but it just made me want to walk around Rome. One day I sat down in the sunlight in Piazza Navona. It was an autumn day, and an old man sat down next to me and asked me about the book I was reading. He wasn’t trying to pick me up. I was attuned enough to know when that was happening. Rather, he began to tell me about the statues around us, about how [Messrs Gian Lorenzo] Bernini and [Francesco] Borromini completed them. I had no idea about any of this. From that day on, I walked around Rome with different eyes, and I fell in love with the city. I’ve never fallen out of love with it since.

___

Find Me starts out on a train to Rome, and the first section really comprises of a number of walks around the city. Elio and his father have a ritual they call “vigils” where they return to a building or corner where something meaningful once happened in their lives – in a sense, standing there, they re-experience the event all over again. Do you have your own vigils?

Vigils are a way of marking time in your life. And yes, I do have my own, just as Elio does. There are certain places in my life where I would like to go back and kiss that person again. It just so happens that my wall is in Cambridge, Massachusetts, not Rome. I think we all have vigils, don’t we?

___

One of the elements I really appreciate about your fiction is that you don’t shrink away from the joys of high culture. We’re always so inundated with pop culture, but your characters delight in classical music, high art, antiquity, philosophy – sacred forms.

They are sacred. And I venerate those things. At the same time, people who read me – even in this apartment, my family [laughs] – often say to me, “Enough with the classical music!” They feel it’s a way of shutting people off. But when you think about Call Me By Your Name, which has sold a lot of copies, I never once mention a contemporary rock musician. I mention [Messrs Johann Sebastian] Bach and [Joseph] Haydn. And people never complained about that. I hope this doesn’t sound arrogant, but even when describing a sexual act, I do want there to be something timeless about it. It’s not just: they’re f***ing. There is something going on here that is more than two bodies having sex. And the same thing happens in art. Basically, I want to access that which is not so time-bound.

___

It’s also impressive that you didn’t write a Call Me By Your Name follow-up that has Elio and Oliver back the very next summer. Like a Call Me By Your Name 2: This Time, It’s Personal. I’m sure a lot of readers expect more of that glimmering tan skin on nubile bodies.

I tried. When going back to Elio, I thought, OK, let’s make him three years older and see where it leads and I realised it just wasn’t working. I didn’t want to make Rocky II or The Godfather Part II. Many fans of the book wrote to me, asking me to please write the next one from Oliver’s perspective. But Oliver wouldn’t have the right perspective. He’d never write a book about it. He would say, “I met so and so, we went to bed. It was great. And maybe I’ll see him again tomorrow.” That’s the alpha voice. What happened in the end was that I was sitting on a train in Italy working on a book about my father. A woman sits next to me, 25 or 26, and she has a dog. She even has a cake box! We start talking. She was going to visit her dad, and she got off two stops later. I immediately stopped writing the book on my father, opened a new document and started writing about this woman I met on the train. I knew at that moment that the book would begin with Elio’s father and he would be going to Rome to meet his son. Elio would be waiting in the wings, and they would go visit the wall together.

___

There is still a lot of sex in the book. Do you find writing sex scenes difficult?

I find them satisfying. I enjoy them. My father once told me something and I bless him for saying it to me. He said, “Whatever you do with someone else, once your clothes are off, there’s nothing forbidden.” No, hurting a person is not OK. What he meant was when you take off your clothing, you also remove your aptitude for shame. If I can say so, I think that’s what Call Me By Your Name means. It means, if you are me, if we’ve gone to the bathroom together, if we vomited together, if we’ve done all the things together, there’s nothing secret anymore. Can we please not have any secrets? Isn’t that the best thing in life? Not to have secrets?

___

In the world today there’s such confusion between fiction and biography. People assume a novel is a veiled memoir, and I’m sure you run into this at every turn with Call Me By Your Name. Readers must assume you had an Oliver, that you were young Elio with a summer just like the one you wrote about. Do you experience that?

Yeah. But I have the opposite situation with my memoir, Out Of Egypt, where I have scenes with dialogue where I was not even born yet. People accused me of writing a novel and not a memoir. So, I get it both ways. People think that many things have happened to me. I’ve had crushes on guys. I’ve done things, but it’s not exactly as it is in the novel. To be honest with you, some of the people attached to the film did try to do what I described with a peach. They wanted to make sure it could really happen. I never tried that. I’ve done many crazy things, but never that. Someone asked, “How did it come to you then?” Honestly, I’ve never lusted after a peach [laughs].

___

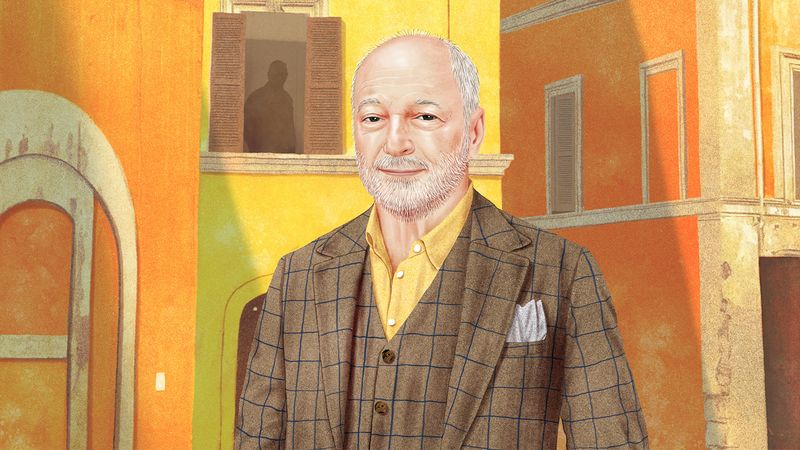

Illustration by Mr Jason Raish