THE JOURNAL

Messrs Ed Harcourt (left) and Ralph Steadman. Photograph by Mr Alexander Clouston

MR PORTER meets artist Mr Ralph Steadman and musician Mr Ed Harcourt. Splattered ink and a musical about beavers ensues .

It is the 1970 Americas Cup and Messrs Hunter S Thompson and Ralph Steadman are restless. They have no interest in the yacht race they have been commissioned to cover, so decide to take matters into their own hands. They swallow some psilocybin. Mr Steadman feels the urge to write expletives about the Pope on the side of a nearby boat (“Are you a religious man, Ralph?” Mr Thompson asked afterwards). Mr Thompson, sensing things are going badly, releases a flare to attract attention, setting fire to a nearby boat.

Such incidents were typical in the course of the pair’s long collaboration – a quest to expose the depravity of the US’s high society (and the American Dream) via Mr Steadman’s corrosive ink drawings, which accompanied Mr Thompson’s acerbic prose. Of course, the antics and words of Mr Hunter S Thompson are often the best documented. But it is interesting to note that Rolling Stone editor Mr Jann Wenner – a man who oversaw the men’s most notable work, including Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas – said in Gonzo: The Life Of Hunter S Thompson, “Ralph [Steadman] was always crazier than Hunter. I knew it and Hunter knew it. Ralph really was a mad genius… He wouldn’t compromise.”

If Mr Steadman’s recent 80th birthday party is anything to go by, his wild days are behind him. “I just drank sparkling water,” he says as he sits in the sprawling garden of his vast Georgian house in Maidstone, Kent. It later transpires that the party included a fight in a river adjacent to the pub, Mr Will Self reading out lottery numbers in a deranged manner, and “an American contingent handing out magic mushrooms”.

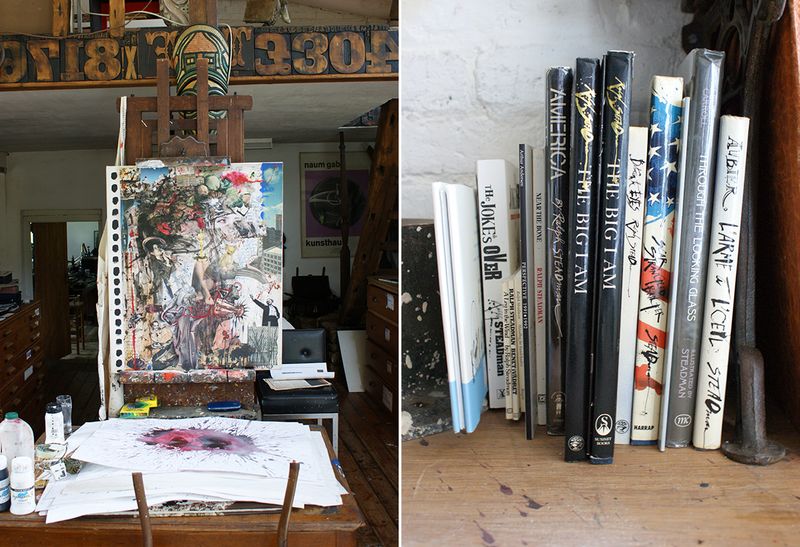

Left, A collage on canvas created for an exhibition called Who?Me?No!Why?, Right, A collection of Mr Steadman’s books, photograph by Mr Alexander Clouston

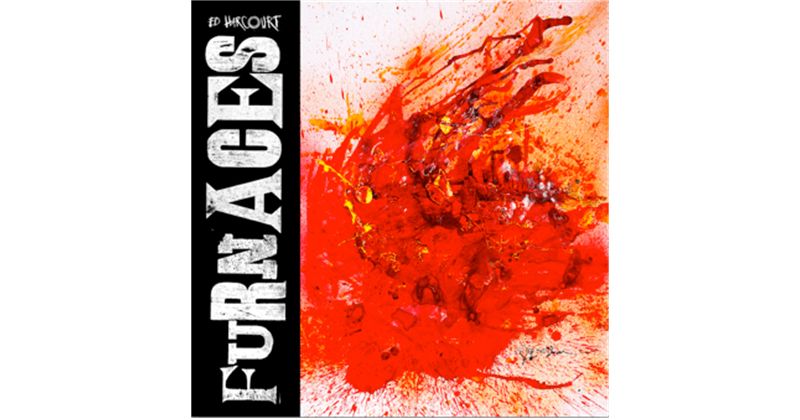

MR PORTER has been invited to Mr Steadman’s place (something he bought in the 1970s “for a song… nobody wanted it”) by the musician Mr Ed Harcourt. The two are friends and Mr Steadman recently lent his nib for the artwork of Mr Harcourt’s seventh studio album Furnaces (Polydor), out today. The fiery etching reflects a heartfelt, eclectic rock record which Mr Harcourt – who was nominated for the Mercury Prize with his debut album in 2001 – says is inspired by his rather cynical view of the future that lies ahead for his children. It is perhaps the best and most varied work of his career to date (listen to it here). “I appreciate [Ralph’s artwork] beyond belief. I started writing the record about four years ago and I had something collaborative with Ralph in mind. I sent him the record and he said ‘Yeah, it’s alright… The wretched, woe is me, the-world-is-ending music’,” Mr Harcourt says, with a smile. Mr Harcourt is also visiting because he wants Mr Steadman to draw – or rather throw – ink on a jacket of his. “Look at it drying beautifully. It’s unbelievable isn’t it? Just natural,” says Mr Steadman, admiring his work.

So how did the pair meet? The facts are hazy, and disputed. As we enter Mr Steadman’s studio, they are more preoccupied with playing vinyl (and a jaw harp and a duck whistle) and discussing drawings. Mr Steadman shows us some work for a new book he is working on called Critical Critters. The scratchy illustrations are coupled with scribblings that show off his knack for wordplay which, whether on the page or in person, is reminiscent of Messrs Spike Milligan or John Lennon (he has a Liverpudlian lilt, reflecting his birthplace). At one point, Mr Steadman prints off a musical he wrote in 1999 about a beaver so that Mr Harcourt can write a score for it. Unless it involves impromptu renditions of Lancastrian poetry (at one point, in answer to a question about how his drawing has evolved, Mr Steadman recites “Albert And The Lion” with perfect comedic timing), or the Dickens-like name of his landlady when he worked in Wales at an ad company (Mrs Clinch) – Mr Steadman is not a details man. But from what we can gather, they met 10 years ago while performing music together.

Mr Steadman adds some finishing touches to a butterfly for Critical Critters, photograph by Mr Alexander Clouston

Mr Steadman is most known for his drawings. Apart from the famous material with Mr Thompson, he has produced children’s books, political satire for Punch and Private Eye, books on Mr Sigmund Freud, and animals – including Extinct Boids and most recently Nextinction (“The publisher said, ‘You can’t have that as a title, it’s not a word’. And I said, ‘Well, it is now, I’ve just said it.’”) He has always been a keen musician, however. He plays us a song called “The Wool To Live” which he recorded for an album titled Abuse – also featuring Madness and Style Council – protesting against animal cruelty. Before our visit, he sends over a track of his called “The Man Who Woke Up In The Dark”. Its melody is as deft as the lyrics are sharp. The title references a quote by Mr Sigmund Freud about Mr Leonardo da Vinci – an important figure for Mr Steadman, and another subject for one of his books.

“I think it falls under the same umbrella. Music, art – as long as you’re creating something,” says Mr Harcourt as the pair sit down for a moment to discuss influences and creative evolution. Mr Steadman agrees. “They intertwangle.” The pair share a passion for the drawings of Mr Paul Hogarth (Mr Steadman also cites “George Gross, Ron Searle, Steinberg, André François, and Picasso” as influences) and the music of Mr Django Reinhardt. Mr Harcourt learned to play the piano – an instrument which features heavily in his music – when he was nine. “But I didn’t start writing songs for me until I was about 21,” he says. He was fed on a diet of Irish folk songs, Mr Johnny Cash and The Beatles by his dad, with a dash of classical music for good measure. It all feeds into Furnaces, which – already receiving positive reviews – he says relied on a good working relationship with Flood (Mr Mark Ellis), a producer who has worked with Mr Nick Cave in the past. “He and I bounced off each other. He was goading me, in a way.”

An illustration which will feature in Critical Critters called "Crazy World Maintenance 1”, drawn in 1992, photograph by Mr Alexander Clouston

So when did Mr Steadman realise that he and Mr Thompson had something special? “It worked because we were so different. He used the fact that I was weird – an English illustrator. We were like chalk and cheese.” Describing when Mr Thompson first saw his drawings, Mr Steadman, adopting Mr Thompson’s American growl, says, “‘every one is a ball breaker’… he couldn’t believe it!” When they first met – on the Kentucky Derby assignment which gave birth to Gonzo – Mr Thompson apparently said, “They told me you were weird, but not that weird.”

“Hunter hated me to write. He said, ‘Don’t write Ralph, you’ll bring shame on your family’. I said, ‘Well, I can write better than you can draw, pal’. He was not a kind person,” says Mr Steadman – who, in the next breath says, with a smile, “People used to give him pills. He’d eat it first and ask ‘What was that?’ later.” One gets the sense that Mr Thompson slightly resented Mr Steadman’s various creative abilities.

With this in mind, we discuss what Mr Steadman might be labelled as. “I’d call you an artist,” says Mr Harcourt.

“Not a musician?” asks Mr Steadman with a smile.

“That too,” says Mr Harcourt.

“Not a poet?” says Mr Steadman. “A Renaissance man,” says Mr Harcourt.

“Ah – a runny essence man? Runny essence…” says Mr Steadman. “Have you got any of those bottles of runny essence please?”

With an ink-splattered jacket and a beaver musical in his hand, it is time for Mr Harcourt to leave. It is not clear whether he will find an opportunity to wear the jacket or put music to Mr Steadman’s musical. But we’d love to see the results if he does.