THE JOURNAL

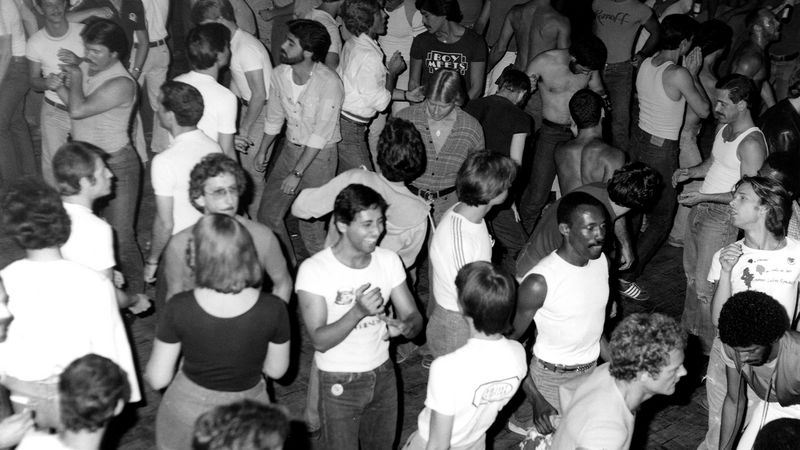

Studio One, California, 1977. Photograph by Mr Pat Rocco, courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries, Los Angeles, and the estate of Mr Pat Rocco

Hangovers used to tell a good story – moustache perfumed with secondhand smoke, bomber jacket flammable from spilled poppers and booze. I’d wake up debased by the fluids of strangers. The cloying aroma of Red Bull, the worst. Now I’m just sore-eyed from screen time, still wearing the “good” sweatpants from last night’s Zoom. On group video calls, we can’t even shout in unison or natter all at once because the loudest person just cuts off everyone else. Even interruption is no longer fun, just another way online socialising can’t compare with the fizz of being in the same room.

Some anticipate we’re due a new Roaring Twenties. I’m not sure how quickly we’ll lose our inhibitions again. It may be pertinent, despite considerably different circumstances, to look back at how nightlife shifted in response to the Aids epidemic. Writing Gay Bar, my book about how places where I hung out shaped my sense of self, I realised how deeply my nascent going-out experiences were beset by fear of disease. In Los Angeles in the 1990s, I found the gay clubs sterile and characterless. At Studio One, the men were as smooth and slick as the fixtures. Gay had become, to borrow a term from sociologist Professor Erving Goffman, a spoiled identity, inextricable from illness. To deflect, both bars and bodies presented as impenetrable and hygienic. In London, new gay bars were unlike what came before (grimy pubs, furtive basements). They boasted large windows and sleek surfaces – contagion-free.

It’d be easy to romanticise the gay life that preceded. At Studio One in the 1970s, men boogied atop speakers shaking fans and tambourines and the place drew A-list celebrities. But there were also reports of racism, sexism and transphobia on the door. Those who did get past the bouncer could become alienated in other ways. “Even the dances have a depersonalised quality,” a Studio One patron told the Los Angeles Times in 1976. “The Hustle or the Bus Stop... people lined up, dancing the same way, completely unattached to each other… like robots. Like lemmings, they begin to form those lines.” He basically foresaw TikTok when he predicted “the day when we all just walk up to the entrance to a disco, put a bunch of quarters in a slot and become immediately surrounded by music. Then each of us will go into a space the size of a telephone booth and dance by ourselves.”

“Mr Freddie Mercury arrived by landing his helicopter on the roof. Another legend has him taking Princess Diana (in boy drag) to the Royal Vauxhall Tavern”

Another Los Angeles spot, Probe, responded to trepidations around Aids with an enterprise that foreshadowed hook-up apps: a voicemail service (976-PROBE) that enabled men to vet one another (or get off) over the phone. By the 1990s, the club itself had become a generic venue, no longer a raunchy private club for butch men. Further back still, it was the Paradise Ballroom, where black and Latino dancers developed a style called posing. Those who appeared on the television show Soul Train brought their moves before a national audience. The dance evolved into punking, then waacking, eventually linking up with voguing on the East Coast. Underground scenes have long cross-pollinated and crossed over into mainstream culture.

As much as a “safe space”, gay bars could be dangerous. In the 1980s, when east London was still considered dodgy terrain, the Shoreditch pub the London Apprentice was a magnet for violence, but its chaotic, seedy reputation continued to draw thrill-seeking gay men. Supposedly, Mr Freddie Mercury arrived by landing his helicopter on the roof. Another legend has him taking Princess Diana (in boy drag) to the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in south London after she’d imbibed peach bellinis. Gay bars have been problematic, but the tales are often fierce.

When we go out again, what I don’t want bars to look like: the internet. I’m bored of everyone self-branded and filtered up, with their curated grids. I don’t want to party in an echo chamber, but stumble into a boozer open to surprise. What shape nightlife will take is uncertain. The self-conscious and uptight clubs after Aids demonstrate how, with good reason, the aftermath of an outbreak can invite caution before abandon. Then again, there were raves and peripheral places such as the insalubrious London Apprentice. However we eventually gather together, it feels increasingly urgent we do so – to meet someone unexpected, move past first impressions, land a good jibe, do something worthy of regret.

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out (Granta Books) by Mr Jeremy Atherton Lin is out now

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, by Mr Jeremy Atherton Lin. Image courtesy of Little Brown