THE JOURNAL

Mr Rafael de Cárdenas in his Manhattan office. Artwork: “11.30pm”, 2016 by Ms Louisa Gagliardi. © the artist

The intrepid architect gives us a tour of his workspace (and tries on the new Santos de Cartier) .

Mr Rafael de Cárdenas and his firm, Architecture at Large, inhabit a Downtown Manhattan office building of no-joke pedigree. Erected in the 1890s by the Gilded Age titans at McKim, Mead & White, it’s a nine-storey Beaux-Arts beauty, crowned with an ornate copper cornice that’s gone fully green with age.

“I like this building a lot,” Mr de Cárdenas says. But he’d like to know more about it, and so, there at the ovular marble table in his office, he flips open his laptop and begins reading aloud from Wikipedia. “Wholesale dry-goods district, round ornamental opening…” He then goes off on a tangent to look up acanthus – a variety of flowering plant common across the Mediterranean and tropical Asia — and then improvises some thoughts on New York’s turn-of-the-century transition from cable cars to its current subway system.

Such information gathering (and riffing) is typical of Mr de Cárdenas, a cultural omnivore who worked in fashion and production design before switching to architecture and launching his firm in 2006. In conversation, he digresses easily – but intriguingly. Soon, he’s embarked on a tale of a trip to Chiapas, Mexico, and the fascination he developed there for a local Zapatista folk hero.

Characters and scenarios like these rattle around his brain, ready to be summoned as the design moment demands. This is perhaps why Mr de Cárdenas is known less for a signature style and more as a conjurer of mini-worlds. What he produces – for clients including Ford Models, Baccarat and Manhattan’s revamped Asia de Cuba restaurant – is a version of luxury, albeit one with cinematically suggestive undertones and the occasional club-kid flourish. His Mayfair boutique for jeweller Ms Delfina Delettrez is populated with modernist Italian furniture and disembodied hands and wrapped in faux-malachite green leather. His early pop-up shops (for the likes of Nike and the niche streetwear brand aNYthing) made a splash with dazzle-camo patterns and webs of fluorescent tape, while the warm metallics and advanced geometry of his more recent retail and residential work retain a subversive edge.

The inspirations for his designs reveal themselves “always obliquely, with a gleeful side-eye, and never the same for two projects,” curator and writer Mr Jesse Seegers notes in the book that Mr de Cárdenas published with Rizzoli last year. Though he studied at UCLA and the Rhode Island School of Design, Mr de Cárdenas, 43, is an unapologetic product of his native Manhattan — specifically, of the 1990s Downtown scene and its hedonistic 1980s shadow.

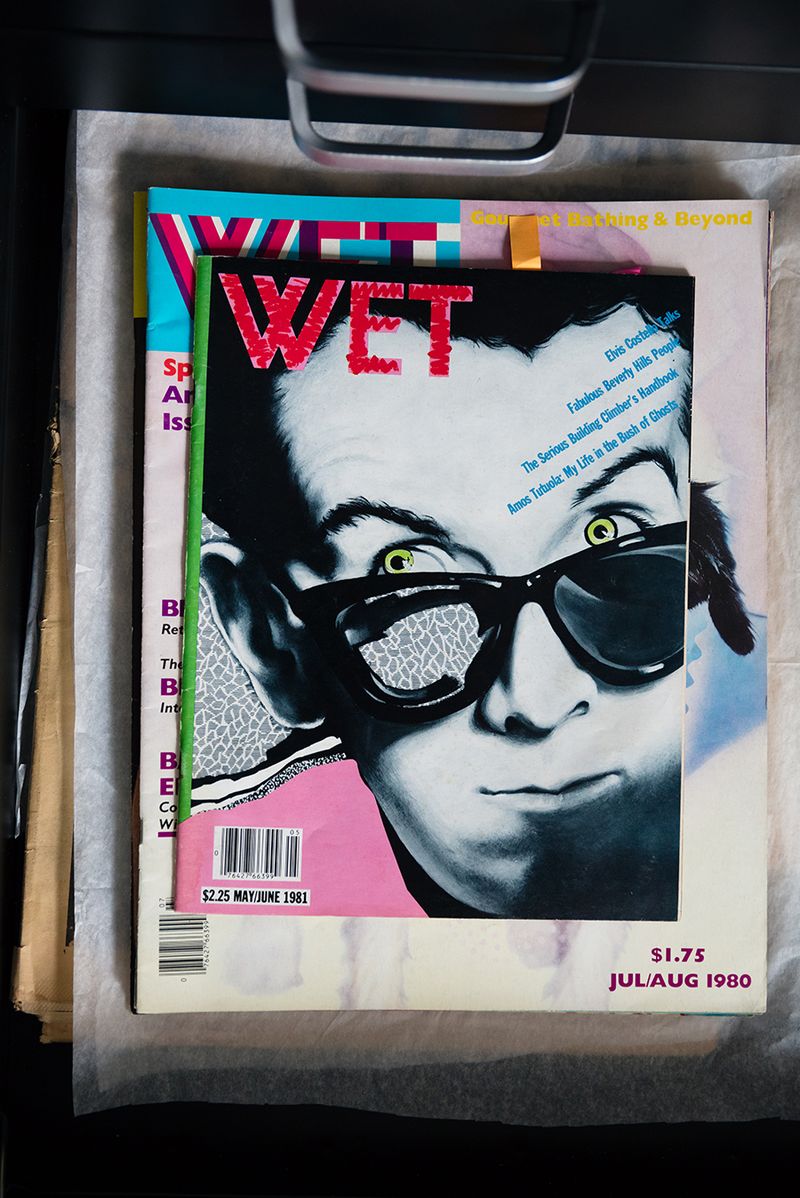

This world – a racy, bygone era of creative intermingling – isn’t really on display in his office. Part of it, however, is stored away in a chest of drawers that he keeps in the casual, sunlit room reserved for meetings and brainstorms: old copies of Interview and Details, as well as Google-proof obscurities with names such as Wet, Eau de Cologne and The Picture Newspaper.

Big-name art – by Ms Vanessa Beecroft, for one – shares space with more outsiders, such as a pair of superhero figurines emerging from spent aerosol containers and a ouija board made from a Ms Whitney Houston album cover. From his shoebox-sized private office, Mr de Cárdenas can gaze out his demilune window and straight at “The Wall”, a minimalist blue mural occupying prime billboard real estate and a central position in the eternal New York battle between art and commerce. Six stories below, on the street that separates NoHo from SoHo, the yellow cabs queue up. Firetruck sirens wail. Mr de Cárdenas eats up the view, but admits that the noise quality here is not a selling point. But he’s got Mses Britney Spears and Donna Summer tunes for that.

His personal style is casual and understated. “I don’t own a tie and I wear sneakers most of the time,” he says. “That probably limits the kind of clientele that I might have at certain points, but I’m doing OK.” Mr de Cárdenas gravitates towards workmanlike and well-crafted Japanese clothes, and not only because the sizing suits him. For this particular shoot, though, he’s trying out something new: the all-steel, 39.8mm iteration of the 2018 Santos de Cartier watch (available exclusively as of today on MR PORTER).

In fact, Mr de Cárdenas’ relationship with the brand runs a little deeper than that. This week, Mr de Cárdenas will be speaking at The Cartier Social Lab, a three-day, symposium-style event in San Francisco, during which a series of creatives – including Messrs Yves Béhar, Ma Yansong and Daniel de la Falaise – will be gathering to discuss daring and innovation, in the spirit of Mr Santos-Dumont, the air-travel pioneer who first commissioned the Santos watch. Aware that not everyone will be able to make this particular get-together, we at MR PORTER thought it as good a time as any to ask Mr de Cárdenas some of our own questions. Scroll down to discover his thoughts on design, working life, inspiration and, yes, his rather enviable collection of 1980s magazines.

This week, you’re talking about “intrepid design” in San Francisco at a symposium organised by Cartier. What does that term mean to you? Not caring too much about what other people think?

You’re always concerned about what people think; it’s a lie to think that you don’t do things in order to have some respect. I mean, sometimes I just want to do projects that make money and be able to go home at six o’clock. And then I get roped into something and realise that I do care, a lot. But my clients are actually in many respects the ones that are taking risk. My relationship with them – my life and job! – would probably go smoother if I didn’t want every new project to be an opportunity to do something I’ve never done before.

Tell me about your collection of vintage magazines, and how they relate to your work.

There may not be a direct design reference there, but it’s still important. They also operate as something like a talisman to me. It was in the 1980s that I became aware that most people didn’t dress weird and have these interesting Downtown lives. So anything that was “niche” in that time, 1980 to 1985, is very alluring to me. Very sexy. I want it, crave it, and want to know all the details.

You also have a lot of plants, I see.

They all come from the same mother, which is at my apartment in Brooklyn. I have a weird attachment to my plants. I feel like if they aren’t doing well, my business isn’t doing well.

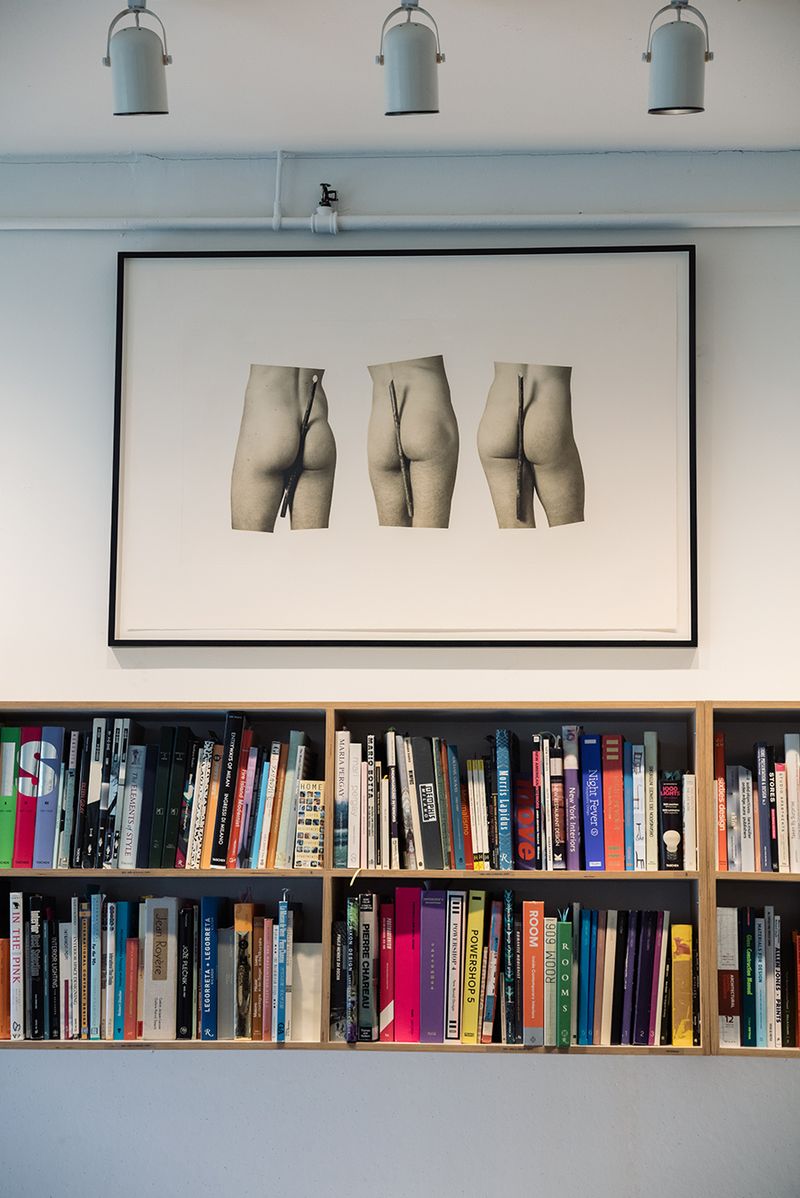

Artwork: “Untitled”, 2010 by Mr Daniel Sinsel. Copyright Mr Daniel Sinsel, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

Is there an actual correlation there, or just an emotional link?

It’s probably a little bit of both. I like mercury in retrograde, the idea that the movements of planets could affect my life. Does it actually, really? No. But do I want to live in a world where magic exists – yes! One hundred percent. Aren’t certain emotions magic? I just can’t believe when people don’t want to live in a world like that.

What’s one thing you consider essential for a workspace?

Music is important. The level of performance and excitement that is happening in a studio is very reflective of the music that’s playing. I’ve been listening to this station that’s just soft rock from the 1970s and 1980s. They’re not that great, but after time, they sound great. And then in the afternoon when you need a boost, we have a little Britney [Spears], a little Kesha, some gay iconography.

Do you like being in this part of town?

I’m in the neighbourhood that I wanted to live and work in my whole life. [Mr Robert] Mapplethorpe lived a couple blocks away. I remember coming to SoHo and NoHo in the 1980s – people dressed kind of weird, there were artists, the architecture was different. I liked the energy. I liked people break-dancing in the street. But NoHo is not at all what it was then.

What happened?

New York has become a showcase for wealth, like any other city in America. I’m sure there’s a nice way to say this. [Pauses.] Rich people don’t make cool shit. They don’t write music. They don’t make art. Anything that they do, I don’t wanna buy. So you need the discriminating intellectual eye of someone like the de Menils, who did not make those things themselves but recognised it, wanted to surround themselves with it, and kind of created this universe. I guess there’s less and less of that kind of person now.

You’ve worked with Cartier on several projects. What’s that been like?

Cartier are risk-takers, I think. It’s in their heritage. And I’m not just saying that. There’s this exoticism and wildness – the Panthère – but always keeping it really elevated. And there’s a lot of creative freedom in working with them. They’re excited about things that some brands might consider polarising.

What’s your favourite project with them?

The most exciting one for me was in Tokyo. We found this Tadao Ando house in the suburbs, took all the furniture out, and brought in this mythological story of the Cartier man. It was a perfect fit for the sophisticated Japanese market. I don’t know if it would have been the same in America or Europe. I think “things” means something different there. Consumerism is, like, a cultural activity in Japan.

What is it for you?

I like things, a lot. I’m also a consumer. I like acquiring things that represent the life that I want, maybe not necessarily the one that I lead. I kind of don’t live in my house very often anymore – I go to the office and I travel six months out of the year for work – so the most I’m ever in New York is two weeks at a time. But I feel lucky to have the things that I have. I’ll be at home watching TV and look around and be like, “Everything in here is my fantasy”.