THE JOURNAL

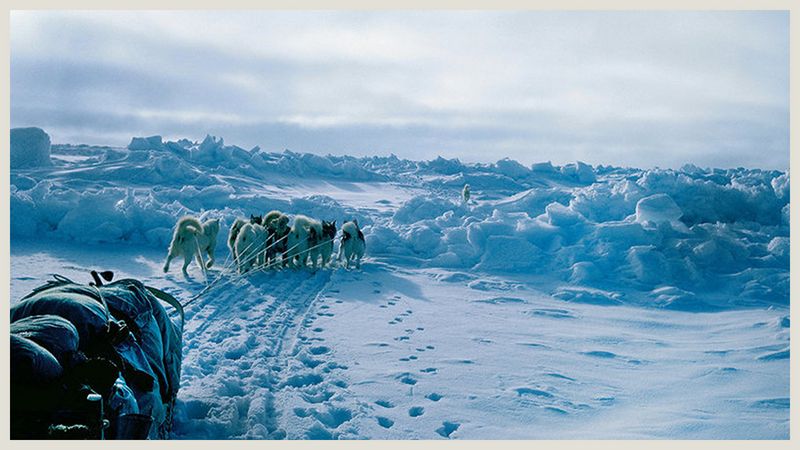

The North Pole, 1969. Photograph © Sir Wally Herbert Collection; www.polarworld.co.uk

Mr David de Rothschild on the men who pointed him in the right direction.

“I think that, in connecting to nature, you connect to yourself,” says Mr David de Rothschild, the founder of the eco-conscious brand The Lost Explorer. He would know. In the course of his own career as an explorer, Mr de Rothschild was among the youngest to traverse both poles, and his expedition was among the fastest ever to cross Antarctica. In 2010, he sailed Plastiki, a boat he’d constructed out of reclaimed plastic bottles, from San Francisco to Sydney. And his Sundance Channel show, Eco Trip, reported on the environmental impact of the lives we live.

“We’re losing our wildness,” he says. “The more connected we are, the more digitized we are, the more we lose our wildness. And I think it’s so important to re-wild yourself, to find that urge, get over the fear, to leave the world of absolutes behind, and go get lost.”

These days, Mr de Rothschild is still regularly getting lost, regularly leading adventures around the world, and, perhaps most importantly, continues to be an important voice on the damage we’re doing, both worldwide and close to home. Here Mr de Rothschild shares a few of his favourite explorers to inspire us for our next trip.

Mr Ben Carlin, Half-Safe

Mr Ben Carlin and his wife Elinore in Paris, June 1951. Photograph courtesy of Guildford Grammar School Archives

In 1958, the Australian explorer Mr Ben Carlin became the first, and only, person to circumnavigate the globe in an amphibious craft (although his wife took much, but not all, of the trip with him). A particularly incredible feat when you take that craft into consideration – a sort of modified Jeep, which the Carlins sailed across the Atlantic. “I also like his story because he’s just an unexpected adventurer,” Mr de Rothschild says. “I mean, he bought this Jeep right after the war and somehow managed to persuade his wife that she should join him. Google ‘Half-Safe’ and you’ll see this tiny little Jeep, barely above the water line, driving out of New York Harbor and you’re like, ‘What the...?’ I’m actually quite interested in doing the same thing that he did. I like the idea of having an amphibious vehicle that goes over land and sea that’s only using clean energy. That was Half-Safe.”

Mr Paul Salopek, Out of Eden Walk

Mr Paul Salopek climbing the steppes in the Mangystau region of Kazakhstan, 2016. Photograph by Mr John Stanmeyer/National Geographic; outofedenwalk.org.

Two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Mr Paul Salopek is just now nearing the end of a planned seven-year walk – called the Out of Eden Walk, as it follows one of the migration paths of early humans out of Africa – covering more than 20,000 miles, from Ethiopia up across the Middle East and Asia, over the land bridge to Alaska and then all the way down the west coast of the Americas to the tip of Chile. “It’s mental,” says Mr de Rothschild. “And it’s so beautiful because it’s a seven-year commitment. And it’s truly back to our roots. It’s very basic. It’s very primal. It’s walking. It’s nomadic. It’s cultural. It’s shifting. It’s moving... but at a really beautiful pace.”

Sir Wally Herbert, British Trans-Arctic Expedition, 1968-1969

Left to right: Messrs Roy “Fritz” Koerner, Ken Hodges, Allan Gill and expedition leader Sir Wally Herbert at the North Pole, 6 April 1969. Photograph © Sir Wally Herbert Collection; www.polarworld.co.uk

Sir Walter William Herbert, aka Wally, was the first man to be given full credit for walking across the North Pole, a trick Mr de Rothschild tried to duplicate many years later. “The Apollo 11 mission was 50 years ago this year,” Mr de Rothschild says. “And, at the same time we were landing on the moon, Wally was walking across the North Pole. I think that’s pretty cool. He went from north to south, from Barrow in Alaska down to Spitsbergen in Norway. And there was ice then, so you could kind of walk from coast to coast, and he went with his dogs, but he had to overwinter at the North Pole, which is incredible. I mean, the fact that he stayed there – he built a shed and actually stayed on the ice, and then continued his journey – it’s just phenomenal.”

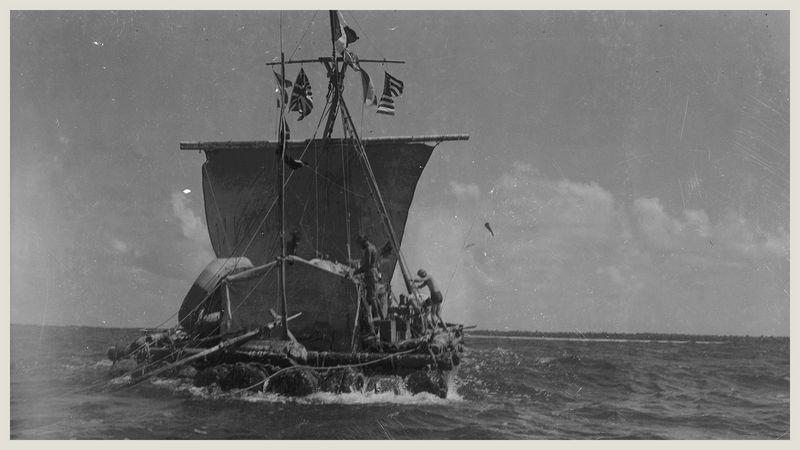

Mr Thor Heyerdahl, Kon-Tiki

Mr Thor Heyerdahl (on the ladder, far right) in front of the Raroia atoll in French Polynesia, 7 August 1947. Photograph courtesy of The Kon-Tiki Museum

In 1947, the Norwegian explorer Mr Thor Heyerdahl sailed a rudimentary raft from Peru to Polynesia in order to demonstrate the migration path of early peoples. His book about the experience is essential reading and was a major influence, obviously, on Mr de Rothschild’s Plastiki. “I’ve always had an affinity with the early guys because they were the forbearers,” says Mr de Rothschild says, “and when they were doing it, there was no Gore-Tex. There were no satellite telephones, no modern safety net; if there was a real problem he didn’t just pick up a phone and call in a helicopter to come and get him, you know? On the Kon-Tiki, when they left, they left. They sailed off into the horizon and that was it. You either made it back or you didn’t. It was Thor Heyerdahl’s mission to articulate that a migratory route going across the Pacific was possible because of currents, and he did it. I think there was such a purity to that mission.”

Mr Benoît Lecomte, The Longest Swim

Mr Benoît Lecomte, San Diego, February 2016. Photograph courtesy of The Swim

Mr Benoît Lecomte set off on his 5,500-mile swim across the Pacific Ocean in June this year, swimming for eight hours a day over six months. “The swim is beautiful, over a long period of time,” says Mr de Rothschild. “And it has a wow factor, which in today’s day and age you need to get people’s attention. If you can understand nature, you can start to learn and understand humanity. And then you can start to respect it, and protect it. Originally, a lot of exploration was obviously a search for resources. Somewhere along the line that shifted to being the fastest to climb this mountain, the first to skate across that ice cap or something. But I think now, more than ever, we’ve got an opportunity to take our time.“