THE JOURNAL

Big Red Piano, Los Angeles (circa 1977). Photograph courtesy of Jim Heimann Collection/Taschen

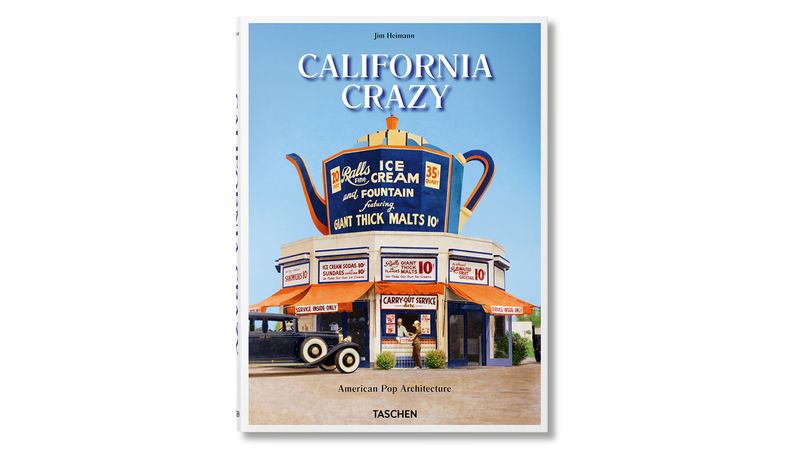

The novelty buildings featured in <i>California Crazy</i> by Mr Jim Heimann are sure to raise a smile.

California is known for its architecture, but not necessarily its good taste. As documented and celebrated by Mr Jim Heimann in Taschen’s recent re-issue of California Crazy, the Golden State has built its image on having the biggest, boldest and brashest, well, everything.

First published nearly four decades ago, Mr Heimann’s homage to American pop architecture is an exciting anthology of the West Coast’s eccentric and sometimes downright surreal approach to roadside-attraction architecture. While the motives behind the construction of these kitsch structures are pretty clear (nothing makes you salivate like a 30ft doughnut looming on the horizon), Mr Heimann uses the pages of California Crazy to explain how these gargantuan billboards became icons of American architecture.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Chamber of Commerce boosters, railway developments and the emergence of Californian real estate supported a series of land developments that continued for more than 100 years. California was transformed. Encouraged by the potential of this relatively untouched region, people arrived en masse and brought with them architectural influences from around the world. And why not? At the time, California was ripe for architectural experimentation.

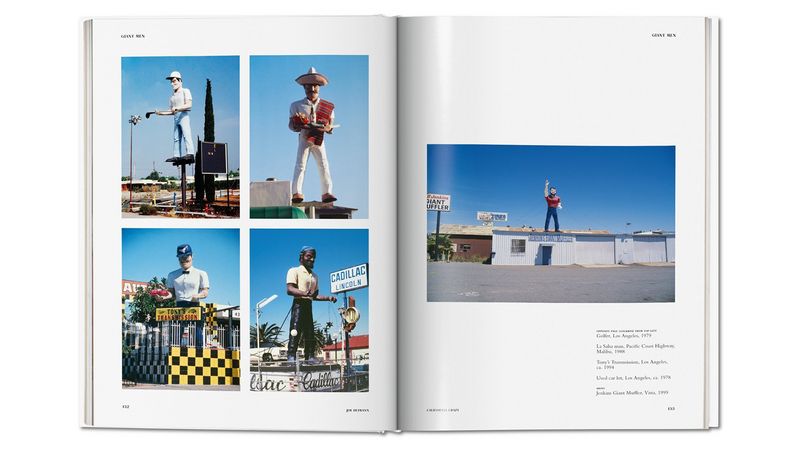

Left, clockwise from top left: Golfer, Los Angeles (1979); La Salsa Man, Malibu (1988); used car lot, Los Angeles (circa 1978); Tony’s Transmission, Los Angeles (circa 1994). Right: Jenkins Giant Muffler, Vista (1999). Photograph courtesy of Jim Heimann Collection/Taschen

This peaked in the 1920s as the age of the car was revving up and local entrepreneurs began building eye-catching, increasingly bizarre structures to entice passing motorists to stop and buy snacks and souvenirs. From dogs to hot dogs, pigs to ships, novelty architecture continued to flourish well into the 1930s. Then new architectural movements, such as the Streamline Moderne style and its Art Deco aesthetic, dazzled the minds and drawing boards of a new Los Angeles crowd.

Alongside striking imagery, California Crazy includes essays on the influences that fostered this nascent architectural movement and identifies the unconventional landscapes and attitudes that allowed pop architecture to flourish. Novelty buildings such as Mr Hugh Comstock’s Tuck Box tea shop (1926) in Carmel are thought to have inspired architects such as Mr Frank Gehry, who designed the Binoculars Building in Venice (1991), which incorporates a giant pair of binoculars designed by Messrs Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen and later become Google’s Southern California outpost.

Whatever your opinion, this book is sure to raise an eyebrow, if not a smile.

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up to our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences.