THE JOURNAL

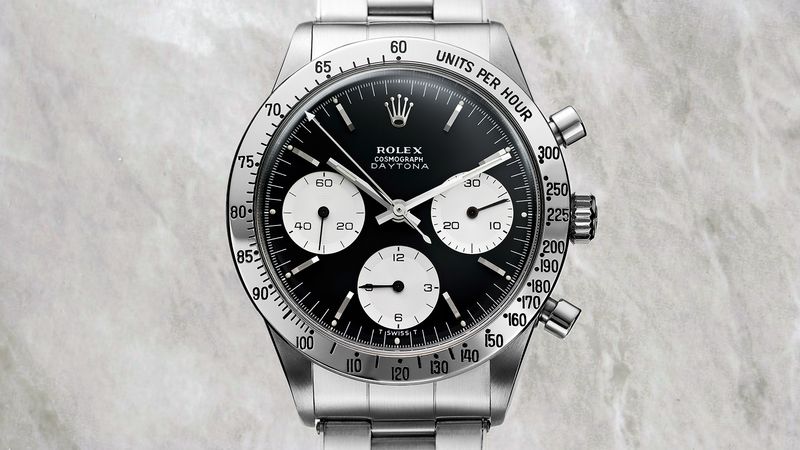

The first ever Rolex Cosmograph Daytona, 1963. Photograph by Mr Jean-Daniel Meyer, courtesy of Rolex

Since their invention more than 200 years ago, chronographs have established themselves as far and away the most versatile additions to the field of timekeeping. The very first was conceived as an aid to astronomical observations; over the years, chronographs have proven indispensable to everything from horse racing to space exploration.

As with all the most practical innovations in watchmaking, they were used extensively in warfare and, in the second half of the 20th century, became indelibly associated with motorsport, particularly Formula 1. Since the turn of the millennium, developments in manufacturing techniques ushered in a flurry of highly advanced chronographs from the world’s top watchmakers, but the chronograph’s appeal remains ubiquitous. Despite the existence of digital alternatives, they are still are prized by pilots and drivers alike, and desire for mid-century models has fuelled a roaring boom in the vintage watch market.

Our guide distills this history to its landmark points, and explains some of the often confusing terminology you’ll find when shopping for a chronograph today.

01. A brief history of the chronograph

Longines stainless-steel chronograph, movement calibre 13ZN, 1946. Photograph courtesy of Longines

1816: Mr Louis Moinet’s Compteur de Tierces

It is an oddity of watchmaking history that until 2012, we weren’t even sure who had made the first chronograph. What we thought was the first ever stopwatch wasn’t even a watch at all, and had neither hands or dials. Mr Nicolas Rieussec’s crude contraption of 1821, (a true “time writer” as the Greek-derived “chronograph” contraction translates), dolloped a spot of ink onto a rotating disc of paper and dropped another when the timed event – usually, a horse race – came to an end.

As it transpired at a Christie’s watch auction in 2012, there was another, older chronograph in existence: a rather boxy, tired-looking pocket watch made in 1816 by Mr Louis Moinet (although, because you look at the elapsed time as indicated by the hands, rather than it being drawn, it is a chrono_scope_ in the strictest Greek sense; just like every other so-called chronograph, in fact). Mr Moinet used it to help make astronomical observations, and, impressively for the first item of its kind, it could measure time down to a 60th of a second.

1821: Mr Nicolas Rieussec’s Timewriter

A design since aped by the Montblanc watch of the same name, it dropped an ink dot onto a rotating paper disc to time horses. A chronograph in the truest “drawing time” sense.

1913: Longines Calibre 13.33Z

The first purpose-built wristwatch chronograph is a “doctor’s watch” with pulsometer calibration. Reportedly, Heuer had equipped doctors with a similar chronograph in 1908, but it was almost certainly a pocket watch repurposed for the wrist.

1915: The first chronograph pusher

Mr Gaston Breitling launched the world’s first wrist chronograph with a push-piece separated out from the crown at two o’clock, to make the operation of start, stop and reset all the more functional.

1923: The first split-seconds chronograph

Patek Philippe was the first watchmaker to accommodate all the finickety components of a split-seconds chronograph in a wristwatch. Need to know more about split-seconds timing? Read on for our guide to chronograph functions.

1934: Breitling No.100 [chk]

A sensational world first, which became the industry norm. Two chronograph pushers rather than one allowed stop, start and reset functions to be more clearly separated, giving better visual balance, too.

1938: Longines Calibre 13ZN

Now enormously sought-after by collectors, the 13ZN (technically, the name for the movement rather than the watches it powered) was the first flyback chronograph wristwatch.

1952: Breitling Navitimer

Launched in conjunction with the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) after more than 65 years of continuous production, the Navitimer is the ultimate pilot’s companion. Famous for its slide-rule dial that enables complex calculations on the fly (sorry), but as you may know, this clever function actually debuted on the original Breitling Chronomat a decade earlier.

1957: Omega Speedmaster

Conceived as a watch for racing drivers, by 1965, Nasa had selected the Speedmaster as standard-issue kit for its Apollo programme, and Mr Buzz Aldrin’s was the first watch on the Moon in 1969. The rest is history.

1963: Rolex Cosmograph Daytona

The eminently collectable Daytona is still a modern classic. First powered by a modified Valjoux manual wind, then Zenith’s El Primero, then in-house mechanics from 2000, it is inextricably linked to motor racing, hence the speedway name, and Mr Paul Newman, whose own example sold in 2017 for $17.8m.

1963: Heuer Carrera

In this, the chronograph’s golden era, Heuer was arguably the biggest chronograph brand of them all. The Carrera was the watch that cemented its reputation (alongside Mr Jack Heuer’s canny marketing moves in the Formula 1 paddock) but the Autavia, launched a year earlier in 1962, has recently attained cult collector status.

1969: The first automatic chronographs

Zenith’s El Primero and Heuer’s Calibre 11 (developed with Buren and Breitling) got the accolades as world’s first automatic chronographs in 1969, but outside Switzerland, Japanese giant Seiko actually beat them to market. Its Grand Seiko line still includes its Hi-Beat 36000, which ticks as fast as the Zenith.

1974: Valjoux 7750

Almost every self-winding mechanical chronograph that costs between £800 and £2,000 is still likely to be driven by this time-proven classic of a base calibre. Rock solid and precise.

1999: A. Lange & Söhne Datograph

A. Lange & Söhne is truly the watchmaker’s watchmaker, and the German brand’s Datograph is considered by many to be the finest modern chronograph in production.

2000-present day: High-tech chronographs

The past two decades have been notable for boundary-pushing chronographs, from TAG Heuer’s string of super-high-frequency pieces (culminating in the 2012 Mikrogirder, capable of timing to 1/2000th of a second) to Audemars Piguet’s 2015 Royal Oak Concept Michael Schumacher Laptimer, the only mechanical watch able to time and record multiple consecutive laps. Honourable mentions should also go to A. Lange & Söhne’s Triple Split (split-seconds timing for seconds, minutes and hours), Bulgari’s Octo Finissimo Chronograph Automatic GMT (the thinnest mechanical chronograph ever made). But arguably, the most significant addition to chronograph watchmaking so far this century comes from little-known start-up Singer Reimagined, who, with the help of a new movement from Agenhor, created a chronograph – the Track 1 – that turned two centuries of established design convention on its head.

02. Chronographs explained

Breitling Premier B01 Automatic Chronometer

Now that we’ve covered the history, let’s explain what the chronograph in all its forms can actually do, and how some of the fancy features that you often hear about from watch brands actually improve the basic experience of keeping track of when things start and stop.

Automatic or hand-wound?

Automatic watches came about in the 1930s, but it took watchmakers until 1969 to produce automatic chronographs (see timeline above). The vast majority are automatic today, but the very finest remain hand-wound, because finely-finished chronograph movements look exquisite and an automatic rotor tends to get in the way.

Clutches and column wheels

This gets a bit technical, but, in the simplest possible terms, chronographs use a clutch system to engage the gears driving the chronograph hands, and either a lever cam or a column wheel to determine whether you are starting, stopping or resetting the chronograph. Older chronographs use lateral clutches, which push gears together when needed; more modern ones tend to have vertical ones where the gears are always engaged. A vertical clutch reduces the hesitant shaking of the second hand when you start the chronograph, while the column wheel makes the “action” of the chronograph – what it feels like to operate; the precision and resistance of the pushers – smoother.

Flyback chronographs

Developed for pilots to synchronise their timings, flyback chronographs can start, stop and reset in the same way as regular chronographs, but they have an extra ability: if you press the reset pusher at four o’clock while the chronograph is running, the hands will fly back (see!) to zero and immediately start timing again. It’s usually touted as a way to record back-to-back events but when it was invented, pilots used to press and hold the reset pusher to ensure timing began at exactly the same instant.

High-frequency

The precision with which a chronograph can time depends entirely on the speed of the watch’s escapement. Makes sense if you think about it – if something pulses back and forth six times a second, like a 3Hz (21,600 vph) movement, how can you stop a hand accurately on a tenth-of-a-second scale? You can’t: for that you need at least 5Hz (36,000 vph) like you find in a Zenith El Primero. Even higher frequencies are sometimes deployed – but are relatively uncommon.

Regatta chronographs

Also called countdown chronographs, because that’s exactly what they do. Aimed at sailors, these are a specialised subset of chronographs that have been modified to count down, instead of up; usually with markings for five-minute increments, as that’s how sailing races are usually started. Some – like Ulysse Nardin’s Regatta from 2017 – are able to count down to the start of a race, then seamlessly start counting up to measure its duration.

Scales: telemeter, tachymeter and pulsometer

We all remember speed = distance/time from our school days, right? Well, with that on board, a chronograph can be used to measure more than just elapsed time. These measurement scales run around the outside of a chronograph dial, or sometimes are etched into the bezel (à la Rolex Daytona or Omega Speedmaster).

Telemeter scales measure distance: let’s say you see a flash of lightning in the distance – stop the chronograph when you hear the crack, and it’ll read off the distance on the dial. These also came in handy in wartime for monitoring artillery strikes.

Tachymeter scales measure speed, if you can start and stop timing over a fixed distance. If it takes you 24 seconds to travel 1km the watch will tell you your average speed was 150kph – but please, don’t do this if you’re the one driving…

A pulsometer is intended to give a read-out of a patient’s heart rate. The dial will say something like “calibrated for 30 pulsations”, which means you time how long it takes to record 30 heartbeats, then the scale will give you your pulse.

Split-seconds or Rattrapante chronographs

The split-seconds chronograph is recognisable close-up by the two seconds hands stacked neatly on top of each other. This enables the watch to time two things that begin together but finish separately – two runners in a 400m race, say. Once running, a press of the “split” pusher stops one of the second hands, while the other continues. Another press instantly catches it up to the leading hand, where the process can be performed again and again. These are often called “rattrapante” chronographs, from the French verb “rattraper” meaning “to catch up”.