THE JOURNAL

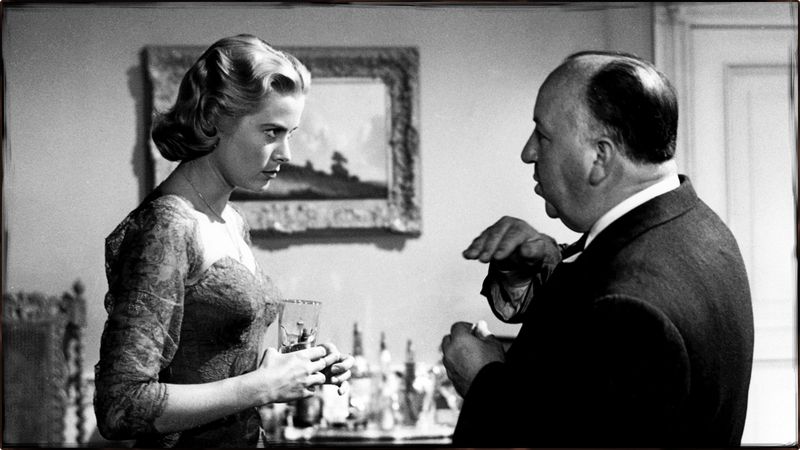

Ms Grace Kelly and Sir Alfred Hitchcock on the set of Dial M for Murder, 1954. Photograph by Warner Brothers, courtesy of Taschen

How the master of suspense kept us at the edge of our seats.

Being wrongly accused of a crime you didn’t commit. Fear of falling. Coming under inexplicable sustained attack from wildlife of a usually peaceable character. These are either notes from your last therapy session or you’ve just been watching the films of Sir Alfred Hitchcock, who mined audience anxieties to create cinematic masterpieces.

In The 39 Steps, for instance, a man is wrongfully accused of murder and must find the criminal himself, and in Vertigo, the film begins with a death from a great height. Then, of course, there’s The Birds, which swiftly turns from romcom to two-winged horror show, Sir Alfred has excelled at exploiting our most primal fears.

An unparalleled knack for manufacturing perturbation is not, of course, the only achievement of Sir Alfred Hitchcock, but suspense and fear have been the foundation of his most acclaimed work. Sir Alfred was “the best architect of anxiety the cinema has ever seen,” writes Mr Paul Duncan, in Alfred Hitchcock: The Complete Films, a new book on the late British filmmaker.

“His subject was suspense and he engineered plots so the audience were kept in suspense as long as possible,” explains Mr Duncan in his opening essay to the coffee-table book, which surveys Sir Alfred’s career across six decades. Including over 50 films with on-set photography, critical analysis and an explanation of how the filmmaker became known as the “master of suspense”, here are four ways in which Sir Alfred excelled at making us all delightfully anxious.

Unsafe spaces

Sir Alfred manipulated all aspects of filmmaking to achieve the goal of edge-of-seat. He would play with sets, as in Rope (1948), where two Harvard graduates kill a former classmate as an intellectual exercise. They do the deed within their apartment, hide the body and host a dinner party, with guests including their college professor, played by Mr James Stewart. The entire film takes place within this confined space. This combined with long, 10-minute takes (the film feels like one continuous shot, the story told in real life) build audience anxiety.

Method-acting madness

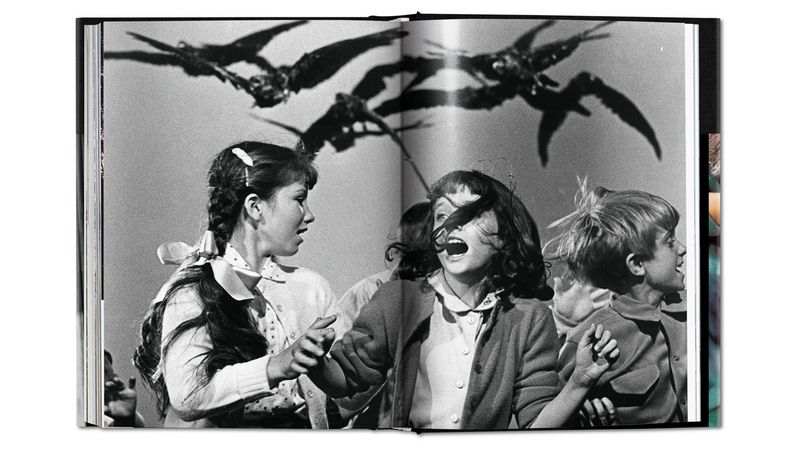

Close confines were imposed on actors, too. In The 39 Steps (1935), actors Ms Madeleine Carroll and Mr Robert Donat were handcuffed for the duration of each day’s filming, just as their characters were. The movie was the filmmaker’s first masterpiece, says Mr Duncan and a scene involving the actors and a pair of wet stockings considered one of Sir Alfred’s sexiest. But his demands on his actors were controversial. One crew member reported their treatment on set as “sadistic”. Later, the director would take method acting to its extremes, when on the set of The Birds, his 1963 horror, lead actress Ms Tippi Hedren claimed to be subjected to psychological torture akin to that depicted on screen.

Spread showing a still from The Birds, 1963. Photograph courtesy of Taschen

Shrill Composition

Sir Alfred’s most famous scene is so lauded it has an entire documentary film dedicated to it. The latter feature is titled 78/52 (2017), and refers to the 78 camera set-ups and 52 cuts it took to create the 45-second shower scene in Psycho (1960). The filmmaker likened his detailed preparation to a composer writing a score for musicians to play, full of screeching violins. He said of his technique: “If you touch off a bomb, your audience gets a 10-second shock. But if the audience knows that the bomb has been planted, then you can build up the suspense and keep them in a state of expectation for five minutes.” The iconic moment from Sir Alfred’s most successful film took seven days to complete and remains a masterclass in suspense.

The Perfect Angle

Long before Sir Alfred arrived in Hollywood, he was famed for elaborate set pieces. In Young and Innocent (1937) he staged a final scene in which the camera zooms 145 feet across a hotel floor to within four inches of the murderer. It was, says Mr Duncan, “one of the greatest shots of Hitchcock’s career” and an “awe-inspiring piece of filmmaking”. But Sir Alfred was also famous for putting the audience in the frame. He developed a style whereby camera movements mimicked audience’s gaze, turning us into voyeurs. With 1954’s Rear Window – which saw Paramount build an entire apartment complex on its studio lot – the viewer is put in the position of the lead character, who cannot leave the confines of his home. “In Rear Window,” Mr Duncan explains, “we are powerless to act as Jeff in his wheelchair”. Finally, we are the ones manipulated by Sir Alfred. We are exactly where he wants us.

In the frame

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up to our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences.