THE JOURNAL

Simon Astridge's Clay House Project, 2016 in North London. Photograph by Mr Nicholas Worley

As Mr Barack Obama’s presidency comes to an end, MR PORTER considers the art of progress, and the value in works not yet completed.

A recent piece for The New York Times by Ms Michiko Kakutani saw the Pulitzer-winning journalist eulogising outgoing US President Mr Barack Obama’s love of books and words. One passage stayed with me in particular, in which Ms Kakutani placed President Obama in a lineage of great American orators. Like forebears President Abraham Lincoln and Mr Martin Luther King Jr, says Ms Kakutani, President Obama’s speeches, “trace how far we’ve come and how far we have to go. It’s a vision of America as an unfinished project.”

Unfinished projects: those moments in-between. They’re seldom celebrated, but so often contain greatness in their own right. So many incremental victories and epiphanic processes can pass us by in a race to get from the beginning to the end of something.

This week’s inauguration is a time during which we might inevitably dwell on endings and beginnings, whatever one’s political persuasion. But it’s also a time in which we might do, as an ever-changing society of 7.5 billion people, as an unfinished project. That the power to grow and achieve exists in imperfect verbs – transitioning, believing, resisting, supporting, empowering – and not always the absolutes of those blunt nouns: beginning; end.

In the following cultural roundup, therefore, we’d like to draw your attention to some other projects that come into their own due to their focus on the unfinished. A series of things – cinematic, musical and otherwise – that pay tribute to the act/art of doing rather than simply completing. Drawing on a host of sources from across time and space, they are things to make you think and things to make you drift, that might prove interesting, inspiring or just plain enjoyable to explore during this week of upheaval.

HR Giger in Jodorowsky’s Dune, 2013. Photograph courtesy of Capital Pictures

Film: Jodorowsky’s Dune, Mr Frank Pavich, 2013

Mr Alejandro Jodorowsky was the Chilean filmmaker responsible for eyecatching efforts such as El Topo and The Holy Mountain, once-seen-never-forgotten slices of 1970s psychedelia. Dune was the Mr Frank Herbert novel adapted by Mr David Lynch into a once-seen-you-wish-you-could-forget-it slice of terrible, terrible sci-fi.

Before Mr Lynch came along, however, Mr Jodorowsky went to great lengths to film his own adaptation of Dune, a folly as grandiose as it was doomed, and one that exists now only in the form of this excellent documentary. Where Mr Lynch cast the likes of Sting for his version, Mr Jodorowsky lined up icons such as Messrs Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles and Mick Jagger to populate the sandy world he envisaged. And what a world it was. Unfinished it may remain, but the movie played a crucial role in film history by assembling the team of Messrs Dan O’Bannon, Jean Giraud and HR Giger for the first time – the special effects/set-design trio who would go on to craft (in my humble opinion) the look and feel of the greatest sci-fi film of all time: Alien (1979).

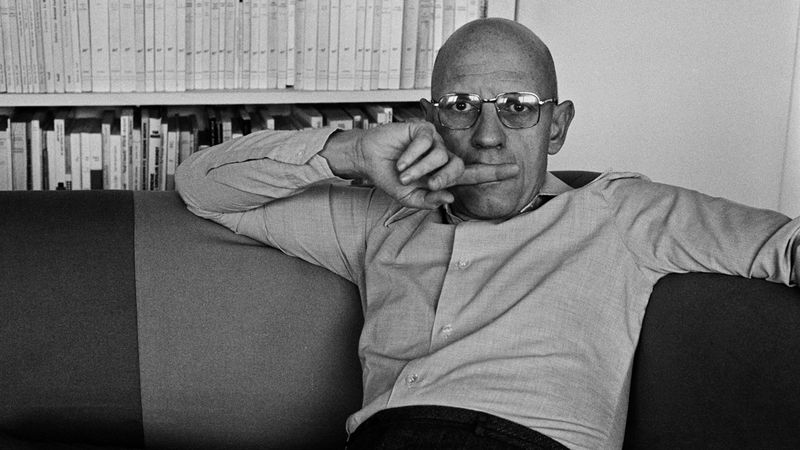

Mr Michel Foucault at his home in Paris, 1978. Photograph by Ms Martine Franck/Magnum Photos

People: Mr Michel Foucault

If you came anywhere near a cultural studies or philosophy class during your formative years, then there’s a good chance you’ll be familiar with the work of French thinker Mr Michel Foucault. One of his biggest contributions to modern thinking was his conception of power not as something that can be possessed and deployed but as something caught up in a continual process of being embodied and enacted:

“Power has its principle not so much in a person as in a certain concerted distribution of bodies, surfaces, lights, gazes; in an arrangement whose internal mechanisms produce the relation in which individuals are caught up.”

(Mr Foucault’s own writing is admittedly obtuse at the best of times, so one of those “beginner’s guide” type books would be more than justified if you do want to explore his ideas further.)

Simon Astridge's Clay House Project, 2016 in North London. Photograph by Mr Nicholas Worley

Architecture: Simon Astridge Architecture Workshop

Mr Simon Astridge is a London-based architect who has enjoyed great acclaim for his quietly powerful work. He conjures not only the large-scale characteristics of a building, but also everything down to the door handles and bannisters. When approaching each new project, he does so – as he describes it – in terms of verbs rather than nouns. For example, when designing a bathroom, he thinks not of bath-tubs but of how to elevate the act of bathing to its pinnacle. In this sense, his projects are never truly complete, transmitted beyond the actual build into the ongoing interactions of people.

Song: “Gustavo” by Messrs Mark Kozelek and Jimmy LaVelle

Whatever you may think of the cantankerous old grouch that Mr Mark Kozelek has undoubtedly proved himself to be when he doesn’t have a guitar or microphone in his hand, his output in recent years makes it hard to argue against him being one of most densely brilliant songwriters working today. “Gustavo”, taken from his 2013 collaboration with Mr Jimmy LaVelle, exemplifies his distinctive, fiercely autobiographical craft. It is also a song that I’ve returned to more and more as rhetoric around immigration and what it means to be American/British/whatever has come increasingly to the fore.

It’s ostensibly a song about a half-built house that Mr Kozelek owns, one that he hires an illegal immigrant named Gustavo to fix up. The aching lyrics speak of who is and who isn’t, who matters and who doesn’t, what we have and what we don’t (“Really, I don’t give much thought to Gustavo,” intones Mr Kozelek, despite the fact that a seven minute song bearing his name suggests quite the opposite.) Ultimately, Mr Kozolek is left not with the American-dream-home he envisaged but a half-finished place he can barely reside in. It is in this moment though that the song transcends it’s melancholy and Mr Kozelek is able to appreciate the unwavering, pastoral beauty he first bought into, one that has nothing to do with, “a place to put [his] mantle clock.”

“Really, I don’t give much thought to Gustavo,” he says, before: “I love to go out to the mountains though. And In the fall feel the breeze blow. And in the winter watch the falling snow. And in the spring love the rainbows. And in the summer smell the roses, white and red and yellow…”