THE JOURNAL

Mr Ralph Fiennes in The English Patient. Photograph by Tiger Moth Productions/Photo12

From Egypt to Timbuktu, here’s how the otherworldly landscapes of the continent have been portrayed on film.

Africa changes you like nowhere else. A lot of travellers have tried to describe the effect Africa has on them, and to capture it in images or on film, but it is hard to convey its power to those who have not experienced it. Anybody who has seen the stars from the Kalahari desert, surveyed South Africa’s Highveld or been scarily close to the wildlife in the Masai Mara knows that feeling quite unique to Africa of being both newly astonished and having a peculiar sense of familiarity, belonging, even homecoming.

Palaeontologists’ theories about the way modern humans evolved in Africa and dispersed throughout the world 100,000 years ago could explain why the continent has this feeling of accord and self-discovery for so many of us. One veteran Africa hand, Mr Brian Jackman writes: “How can you explain the fascination of this vast, dusty continent? ... Could it be because Africa is the place of all our beginnings, the cradle of mankind, where our species first stood upright on the savannas of long ago?”

Perhaps. If so, then at some deep level we all belong to Africa. We all have a secret source there.

Many of the films made in Africa by non-Africans – even those as recent and celebrated as Out Of Africa, which won seven Academy Awards, and The English Patient, which won nine – are often now viewed as unacceptably colonialist in their approach, simply for portraying the experiences of non-Africans. Yet this is a loss. Africa has revelations for us all, and there are some films that can give us a sense of that, visiting it revealingly, even – or especially – for those who have yet to experience it for themselves.

Out Of Africa (1985)

Mr Robert Redford and Ms Meryl Streep in Out Of Africa. Photograph by Universal Pictures/Photo12

Mr Robert Redford plays the Honourable Denys Finch Hatton, a big-game hunter and lover of Ms Meryl Streep’s Baroness Karen von Blixen in Mr Sydney Pollack’s sumptuous adaptation of her memoir, Out Of Africa. This is the classic, deeply nostalgic account of aristocratic Europeans relishing some of the most beautiful country to be found in all Africa before it was changed by the pressures of the modern age, and its cinematic adaptation did it full justice. Baroness Blixen left her Danish home for a farm in the Ngong Hills near Nairobi in Kenya (then British East Africa) in 1913. She married her Swedish second cousin, Baron Bror von Blixen-Finecke, and set up a 6,000-acre coffee plantation high above the plain. The marriage did not last, nor did the plantation’s prosperity, but Baroness Blixen’s passion for Africa did. She had to leave Kenya in 1931 to be treated for syphilis and never returned, but it remained the centre of her life and work. At the heart of her feelings about her life in Africa was Mr Finch Hatton, an Eton and Oxford-educated charmer, who refused to be tied down, though she worshipped the ground on which he walked. The film features both astounding views and remarkable wildlife sequences. Mr Pollack gives the whole movie a leisurely, expansive pace that makes it a kind of dreamlike, para-safari in itself. And then there’s Mr Finch Hatton’s plane, a gorgeous Tiger Moth, which floats Baroness Blixen, and us the viewers, through rift valleys, over arid plains and salt pans covered with flamingos, offering “a glimpse of the world through God’s eyes”, as the Baroness says at the start of the film.

White Mischief (1987)

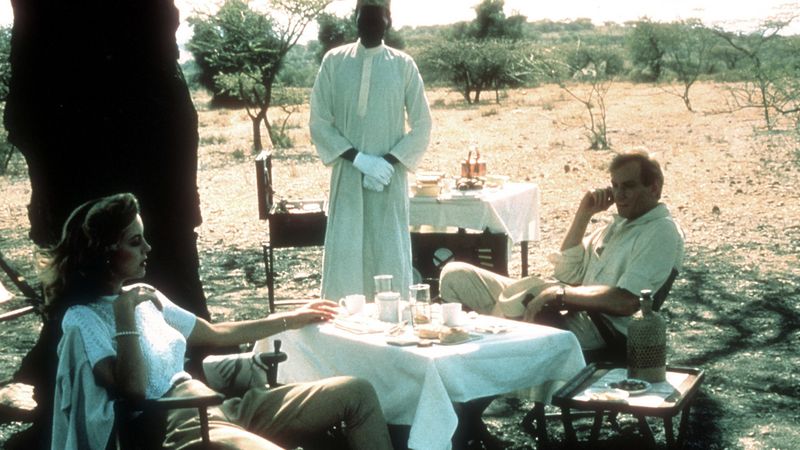

Ms Greta Scacchi and Mr Charles Dance in White Mischief. Photograph by Photo12

And here’s the satyr play to Out Of Africa’s tragedy, the degenerate version of the Happy Valley story that Baroness Blixen made so appealing. In Kenya in 1940, the high-mindedness of a previous generation in Africa has descended into sybaritic decadence. Diana (Ms Greta Scacchi) is 30 years younger than her husband, Sir Henry “Jock” Delves Broughton (Mr Joss Ackland), and soon falls for the charms of the rakish Earl of Erroll (Mr Charles Dance), whose other lovers include Alice de Janzé (Ms Sarah Miles) and Nina Soames (Ms Geraldine Chaplin). It’s a world in which anything goes – “rather a weekend of ecstasy than a lifetime of drudgery,” to quote the film – but Jock snaps and Erroll is shot dead in his car. Alice masturbates by his corpse in the mortuary, a nice touch, while Delves Broughton stands trial but is acquitted. “Welcome to paradise,” says Erroll on meeting Diana. This is a paradise that’s lost, if not squandered. A true story, lightly novelised by Mr James Fox, and salaciously directed by Mr Michael Radford.

Timbuktu (2014)

Messrs Ibrahim Ahmed and Omar Haidara in Timbuktu. Photograph by Les Films du Worso/Photo12

This is by far the most beautiful and authentic film to come out of Africa in the past few years. Written and directed by the Mauritanian master Mr Abderrahmane Sissako, it presents a parable-like story of a Malian cattle herder who accidentally shoots a fisherman after an altercation about the killing of a cow. He is then subjected to the harshness of Sharia law by the invading jihadists who have taken over Timbuktu, riding around on motorbikes, toting AK-47s and mobile phones. As the story unfolds, we see many other inhabitants of this ancient city suffering from this tyranny, too. Music is banned. A couple are stoned to death for adultery. Sports are forbidden, so football is played with an imaginary ball. A fishmonger must somehow wear gloves to cover her hands. And all the while, it is the exquisite landscape and the gentle pace of life that stand against this ideology, a vision of what Africa following its own ways can be. Superbly filmed by Tunisian cinematographer Mr Sofian El Fani, Timbuktu was made in and around the small oasis town of Oulata in Mauritania, a Unesco World Heritage Site that was an important caravan city in the 13th and 14th centuries until it ceded its trade to nearby Timbuktu. A grave warning, but a visual treat not to be missed nonetheless.

The Sheltering Sky (1990)

A scene from The Sheltering Sky. Photograph by Mondadori Portfolio

Mr Bernardo Bertolucci’s film is a good deal less nihilistic than Mr Paul Bowles’ 1949 novel on which it is based, but would it be bearable if it were not? It is still one of the great desert films, primarily about these beautiful, ever shifting, never controllable landscapes that expose the littleness of human endeavour. An American couple, Port (Mr John Malkovich) and Kit (Ms Debra Winger), come to Tangier in 1947 for a trip into the Sahara. They plan to stay a year or two in the hope of rekindling their marriage, but as they travel on into Algeria, it all goes wrong. Port visits a Berber prostitute. Kit sleeps with their mutual friend. Port contracts typhoid and dies. Kit sets off alone into the desert. After joining a camel caravan, she is held captive far away in Niger and ends up mute and half mad. Commenting remotely on all this, from a hotel bar in Tangier, is Mr Bowles himself, who was 80 at the time: “Death is always on the way... But because we don’t know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. Yet everything happens a certain number of times, and a very small number, really... How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps 20. And yet it all seems limitless.” The Sheltering Sky was filmed in various locations in Morocco, rather than Algeria itself. No matter. The desert filming here compares to Zabriskie Point, Woman In The Dunes or Fata Morgana.

The English Patient (1996)

Mr Ralph Fiennes in The English Patient. Photograph by Miramax/REX Shutterstock

In Italy, near the end of WWII, a young nurse (Ms Juliette Binoche) lovingly tends to a dying man (Mr Ralph Fiennes) who is severely scarred by burns and known only as the English patient because he cannot recall his own identity. All he has with him is a copy of Herodotus, interleaved with memorabilia. This sardonically humorous near-corpse (he calls himself “toast”) is not English, though, and his story, revealed to us in complex flashbacks, is searing. Before the war, Count Lazlo de Almásy was a cartographer mapping the Sahara on the border of Libya and Egypt for the Royal Geographical Society, part of the dashing, mostly British International Sand Club, although he is Hungarian. In the desert, he meets Geoffrey and Katharine, an English couple with a Tiger Moth (played by a slightly plump Mr Colin Firth and his perfect blonde wife Ms Kristin Scott Thomas). Lazlo and Katharine embark on a wildly sexual affair. Vengefully, Geoffrey tries to crash his plane, with Katharine on board, onto Lazlo, in a distant wadi, but succeeds only in killing himself and injuring her. Lazlo goes off to seek help for Katharine, but sides with the German invaders. He ends up so burned and traumatised he loses his very identity. Based on the Booker Prize-winning novel by Mr Michael Ondaatje, this is high romantic tragedy, deftly directed by Mr Anthony Minghella, beautifully filmed in Tunisia and hugely admired. It was nominated for 12 Oscars and won nine. Mr Anthony Lane of The New Yorker not only greatly appreciated both Hana and Katharine (“When did you last see a movie that offered two great roles for women?”), but perhaps even identified with the patient, too. (“They meet only in the mind of the patient, and you can imagine him mulling over the pair of them, tasting his impressions like wine.”) At any rate, he concluded, “Man to man, this is awfully close to a masterpiece.” And, man to man, exquisite as the Italian settings are, too, it’s one of the great stories to have come out of Africa.

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Mr James Stewart and Ms Doris Day in The Man Who Knew Too Much. Photograph by REX Shutterstock

Mr James Stewart stars as Dr Ben McKenna in Sir Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 Technicolor remake of his own 1934 British black-and-white film of the same title. “Let’s say the first version is the work of a talented amateur and the second was made by a professional,” Sir Alfred told Mr François Truffaut. Much was altered. In the first version, which starred Mr Peter Lorre, a British family is on holiday in Switzerland when they are caught up in an assassination plot that culminates back in London at the Royal Albert Hall. For the remake, American Dr McKenna, his wife Jo, a singer (Ms Doris Day), and their son Hank are adventurously, for the period, holidaying in Morocco. En route from Casablanca to Marrakesh, they meet Louis, a mysterious Frenchman. The next day, in the hectic Jemaa el-Fnaa market square, Louis dies after being stabbed, but not before he has gasped out to Hank a secret that endangers the boy’s own life. In 1956, this marketplace, filmed for real, after difficulties with Ramadan and Ms Day objecting to the locals’ treatment of animals, was a rare exoticism, a bit further than a budget flight away then. Just before the stabbing (at 25.42 minutes), you can, as always, spot Sir Alfred himself, with his back to the camera, watching acrobats. A brief visit to Africa here and, of course, que sera, sera.

Death On The Nile (1978)

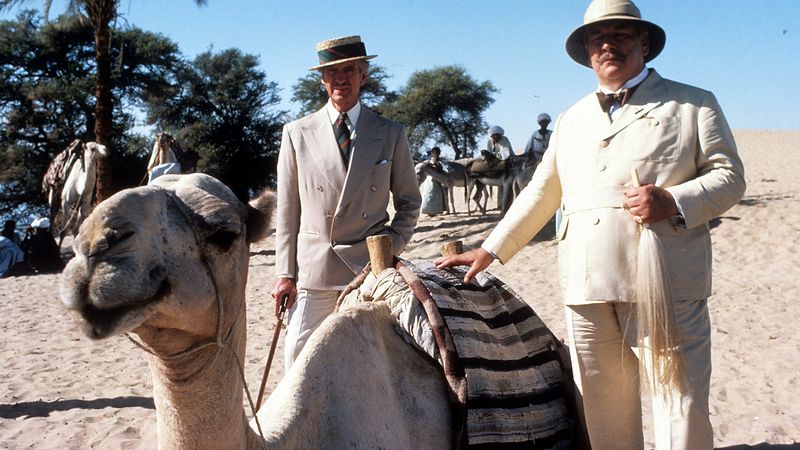

Mr David Niven and Sir Peter Ustinov in Death On The Nile. Photograph by EMI Films/Getty Images

Here’s a special version of Ms Agatha Christie’s country-house/locked-room mystery: a period paddle steamer on the Nile, although the passengers might as well be on an island or confined to a vicarage. Poirot (Mr Peter Ustinov) and his friend Colonel Race (Mr David Niven) have plenty of villainous possibilities with this cast, which includes Mses Bette Davis, Maggie Smith, Jane Birkin, Angela Lansbury and Mia Farrow among other attractions. Filmed on location in Egypt, over seven weeks aboard the historic ship PS Memnon, this cruise takes in many of the ancient sights, if not necessarily in the right order. Make-up call was at 4.00am, shooting began at 6.00am to avoid the midday heat. Ms Davis, who was 70 and playing an elderly American kleptomaniac, had the right attitude no doubt, when she complained, “In the older days, they’d have built the Nile for you. Nowadays, films have become travelogues and actors, stuntmen.” Built the Nile! But at least we can enjoy our eventful armchair cruise.

The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

Sir Roger Moore and Ms Barbara Bach in The Spy Who Loved Me. Photograph by REX Shutterstock

Many aficionados think this was Sir Roger Moore’s finest outing as Bond. Much of it takes place in the villain Stromberg’s underwater base Atlantis, but there are memorable early sequences in which Bond travels across Egypt with KGB agent Major Anya Amasova (Ms Barbara Bach, not yet married to Mr Ringo Starr) and encounters that impressive monster Jaws (Mr Richard Kiehl). These scenes were filmed in multiple locations in Egypt, including the Great Sphinx of Giza. However, as the scene takes place at night, lighting problems caused the pyramids to be replaced with miniatures. Sorry.

Blood Diamond (2006)

Mr Djimon Hounsou, Ms Jennifer Connelly and Mr Leonardo DiCaprio in Blood Diamond. Photograph by Warner/Photoshot

Mr Leonardo DiCaprio, in the same year as The Departed, turned in a fine performance as Rhodesian gun-runner Danny Archer, who hears in prison of a huge, rare and incredibly valuable rough pink diamond that has been found in a riverbank by fisherman Solomon Vandy (Mr Djimon Hounsou). He decides it is his ticket out of his troubles, but this is Freetown, Sierra Leone, in the middle of civil war, and the rebel Revolutionary United Front is advancing. Archer, Vandy and Maddy (Miss Jennifer Connelly), an American journalist trying to expose the illicit diamond trade, get caught up in frightening violence. Mortally wounded, all Archer ends up with is the ravishing African landscape as he says his farewells. Filmed in South Africa and Mozambique, Blood Diamond satisfies equally as a furious action film, a polemic against a dubious trade and as a portrayal of a land that is still beautiful, even in such horrific conflict.

The men featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse

MR PORTER or the products shown