THE JOURNAL

“My Pal Keith Died Too Young, But He Showed Me What The Bonds Of Male Friendship Really Mean”

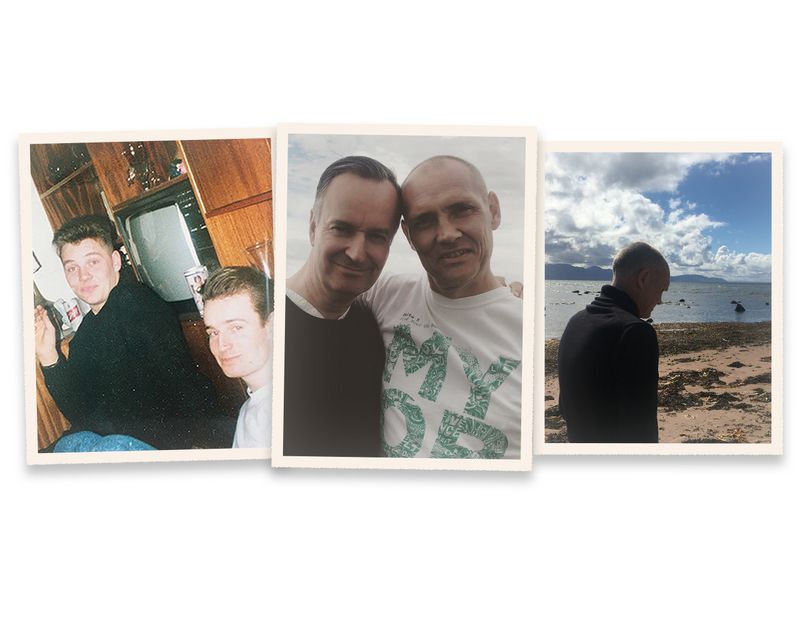

From left: Messrs Keith Martin and Andrew O'Hagan, Castlepark, Irvine, January 1988. Messrs O’Hagan and Martin, July 2018. Mr Martin, Seamill Beach, Ayrshire, June 2018. All photographs courtesy of Mr Andrew O’Hagan

When my father entered his final illness in hospital, he didn’t receive any visits from male friends and he never asked for any. He’d had wives, he had siblings, he had sons, but he didn’t have buddies the way I’ve always had, and the bonds of affection in his life were implied rather than enacted, even as he left it all behind. The idea of hugging another man had always seemed repellent to him. All in all, my father lived a loner’s life, leavened by a handful of old acquaintances who helped him stay sober or who provided a ready audience on the phone. He was competitive with his sons. I think it was because he never really allowed himself to depend on any of us, which is a crucial aspect of love.

So I grew up reaching for the obligations of buddyhood. To this day, I love camaraderie and the sane-making protections of male friendship. I probably have more female friends nowadays than male ones – and that can have a different poetry – but to be great pals with a male contemporary is to have a friendly shadow in the inner sanctum. I’m not going to get into a debate about what’s male and what’s not. If a person tells me he’s a man, then that is good enough for me. We assign our selfhood to ourselves. I know once that person is my buddy, I will rely on him for a very particular connection, not better than any other, not worse, not more or less important, but what it is – a keen and necessary fellowship. A special element can exist in friendships where your physical experience feels similar. Call it empathy, or a sense of equal fallibility.

I grew up loving Peter Pan and the Lost Boys. The kids in Mr Rob Reiner’s movie Stand By Me felt like they could have been pals of mine and the central pair in Mr Jack Kerouac’s On The Road were like the best of my chums. In childhood, I found my very own Huckleberry Finns, first in a boy called Mark MacDonald, who wrote and fished and stole with me and played chess with me every day, all in one long, summer-seeming part of my early life, then he disappeared and I never found him again.

“Keith was heroic in youth. He had the funniest patter in Ayrshire, the highest cheekbones in Scotland, the best record collection in Europe and we changed each other’s lives”

After that, I had a whole group of teenage buddies, who shared the great heights and humiliations of teenage life, and one special mate, Keith Martin, who seemed to need me as much as I needed him. Keith was heroic in youth. He had the funniest patter in Ayrshire, the highest cheekbones in Scotland, the best record collection in Europe and we changed each other’s lives. He was in punk bands, he was political and we energised each other for nearly four decades. When I met him, he was a factory worker who needed to get out, for the sake of his mental health, and I helped him. He wasn’t sure he could do it, he lost his way in the early 1990s, but with acres of soul brotherhood from his friends, he ended up an inspirational teacher in Glasgow.

We had the friendship our fathers never had – the friendships they never had with us – and making up for that lost connection was always part of our brief. My best friend was creative and he wanted the world to be better than it was, starting with himself. And that’s what you want in a lifelong friend: a self-deprecating hero, ambitious for good times. Men have so many gender clichés attached to them – feel this, prove that and suffer your doubts in silence – that I feel proud of how much we escaped into friendship. We discovered freedoms that were never dreamed of in our fathers’ philosophy, the freedom to say, “I need you,” the freedom to say, “My pain is not a secret weapon.”

My pal Keith died too young, but before he went, he was able to show what the bonds of male friendship really mean, and they didn’t mean silence and refusal, in the end, but dependency and love. We thought we would live for ever, but we lived for a day, and what a charm there was in that.

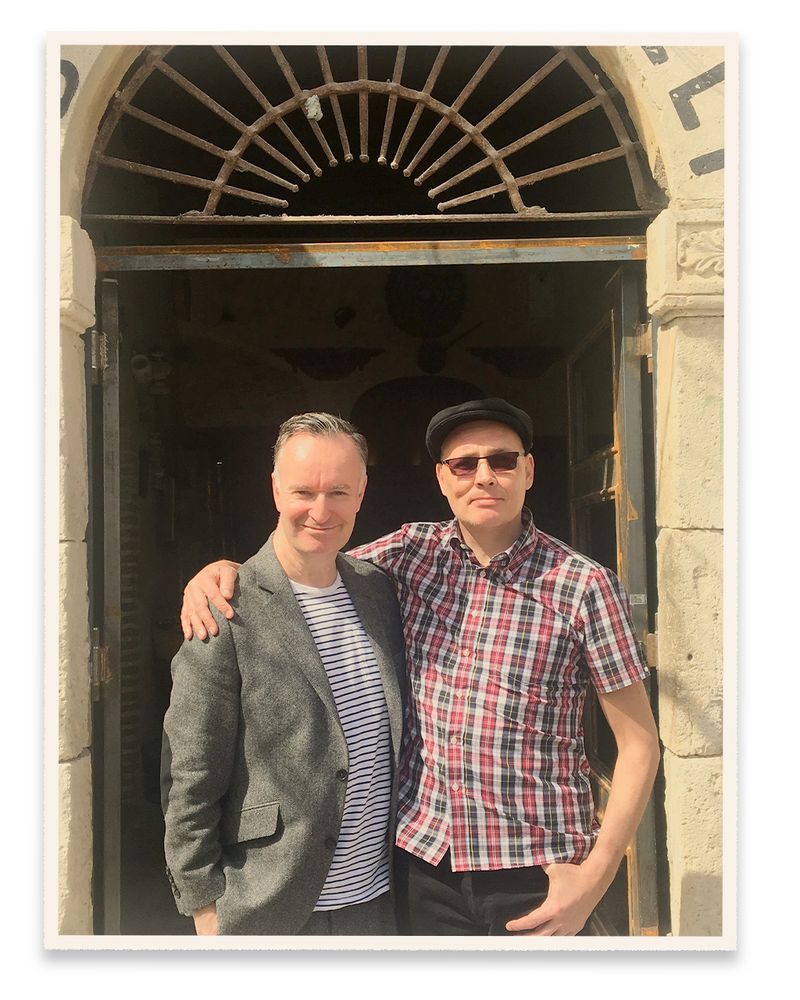

Messrs Andrew O’Hagan and Keith Martin, Savoca, Sicily, March 2018. Photograph courtesy of Mr Andrew O’Hagan

The journey out of childhood was our story. Everybody’s story. And in the end it was a novel. Keith knew it and asked me to write it. When Mayflies was published this summer, I was overwhelmed by the responses, especially from men, many of whom told me they thought all great friendship stories had to be female, or that all the great love stories had to be romantic.

In lockdown, we began to yearn for the opposite of isolation and some of us saw it in the male friendships that had sustained and enriched our lives. For me, the hope was always that we might forge a new way of being a man among men – less macho, more tolerant, feminist and communicative – all the better to make the world fit for purpose, starting with the world in our own heads. I wrote Mayflies to summon that world, and it all began with a bunch of stylish young guys in the 1980s who stood by me.

Mayflies_ (Faber & Faber) by Mr Andrew O’Hagan is out now_. Read more of Mr O’Hagan at andrewohagan.com