THE JOURNAL

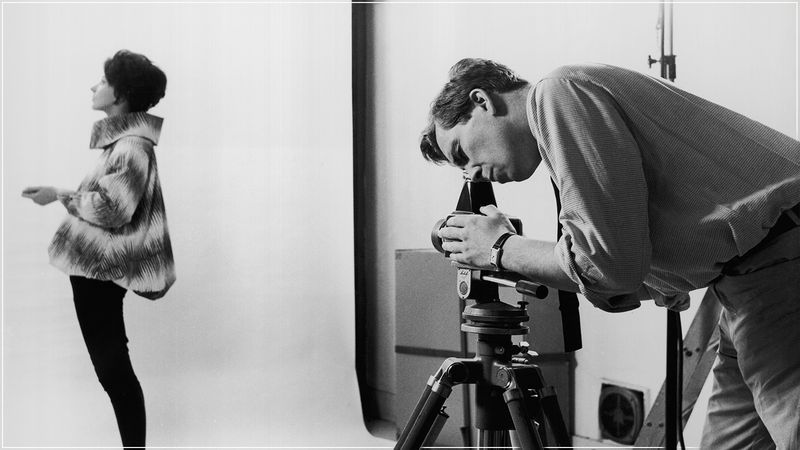

Lord Snowdon, studio portrait, c.1960. Photograph by Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

A portrait of Lord Snowdon, the water-skiing, Norton-riding photographer and brother-in-law to the Queen .

It was Mr Anthony Armstrong-Jones’ marriage to Princess Margaret on 6 May 1960 that, for better or worse, defined the soigne photographer’s life – titleless by birth, the fashion plate was ennobled in 1961 when he was made earl of Snowdon. His death last month, at the age of 86, marked the passing of the first commoner to have married a British monarch’s daughter for more than 400 years. And not just any monarch’s daughter: as well as being the king of the United Kingdom, Princess Margaret’s father had been the last emperor of India. Not a bad match for the polio-afflicted son of a lawyer.

And it was the sleek, elegant and determinedly unflouncy dress the Princess wore for the wedding – a wedding seen by a worldwide TV audience of 300 million – that typified Mr Armstrong-Jones’s impact on the royal family. Sir Norman Hartnell was, technically, the dress’s designer and as ever keen on glitter and bountiful decoration; but it was Mr Armstrong-Jones who imposed his ideas on a reluctant couturier and ensured that the dress – which showed immense restraint compared to those that went before it – became an emblem of modernity.

“He liked modern clothes: he was one of the first to champion the black rollneck”

Lord Snowdon, London, 1958. Photograph by Mr Tom Blau/Camera Press

For modernity was what the Earl of Snowdon brought to the royal party. Cool, too: a dashing photographer even before Mr David Bailey made the profession fashionable, he brought a raffish elegance to a family that had, since the abdication of the Duke of Windsor, eschewed style and glamour. An example: after his marriage, he was appointed artistic advisor to the new and very influential Sunday Times Magazine. During Ascot Week, he would don his black leathers and roar from Windsor Castle to the magazine’s offices on his 500cc Norton, put in his shift – he was a paid-up member of the National Union of Journalists – race back to the castle, shrug on morning dress for the royal carriage procession, and then leave after the first race to go water-skiing. He loved his motorbike, and so did Princess Margaret, who would ride pillion as he zoomed around town. He once stopped the motorcade he was riding in, “borrowed” an outrider’s motorbike and zipped off with the Princess on the back. Indeed, he loved speed: at first he drove a souped-up Mini Cooper, but swapped it for a soft-topped Aston Martin.

He liked modern clothes, too: he was one of the first to champion the black rollneck and even sported a white one to Buckingham Palace – a bold tilt at protocol, which shocked the more stuffy courtiers. After leafing through images of the era for inspiration, designer Mr Tom Ford said he was “stunned by Lord Snowdon’s bold choices in clothes”, noting that he saw the Earl as brilliantly fulfilling the role of “‘groovy photographer’, striding through the airport in suede and [La] Dolce Vita shades.” In Mr Ford’s favourite image of the Earl, he is “wearing a suede jacket, bracelets and rings and an absolute killer pair of knee-high lace-up suede boots that seem to be part hippy, part American Indian and definitely a brave fashion choice”.

Lord Snowdon driving with Princess Margaret in Padua, Italy, 1964. Photograph by TopFoto.co.uk

Not everyone approved: the novelist Mr Kingsley Amis called him “a dog-faced tight-jeaned fotog [sic] of fruitarian tastes such as can be found in dozens in any pseudo-arty drinking cellar in fashionable-unfashionable London.” And Lord Snowdon didn’t always get it right: when he designed and stage-managed Prince Charles’ investiture as Prince of Wales at Caernarfon Castle, he cooked up for himself a tight, forest-green suit with numerous zips up the front that some, charitably, saw as a homage to Mr Pierre Cardin; the Duke of Norfolk, who in his hereditary role as earl marshal was responsible for great ceremonial events such as the investiture noted “he should have worn a hat and pretended to be Robin Hood.” (American journalist Ms Barbara Walters wrote that he looked like a “little elf”.) The Earl got on well with the Duke at Caernarfon, but clashed with Garter King of Arms, England’s senior heraldic authority at the ceremony: “Oh, Garter darling,” Lord Snowdon quipped, “couldn’t you be more elastic?”

Garter King of Arms was aeons adrift of the hip ’n’ happening Lord Snowdon, though the Earl had his conventional side: as an undergraduate at Cambridge, the then Mr Armstrong-Jones was photographed in a leather jacket with an upturned collar, but also coxed the Cambridge eight to victory in the 1950 Boat Race, allegedly putting off the Oxford cox by the ferocity of his sledging – he was known for his ripe vocabulary.

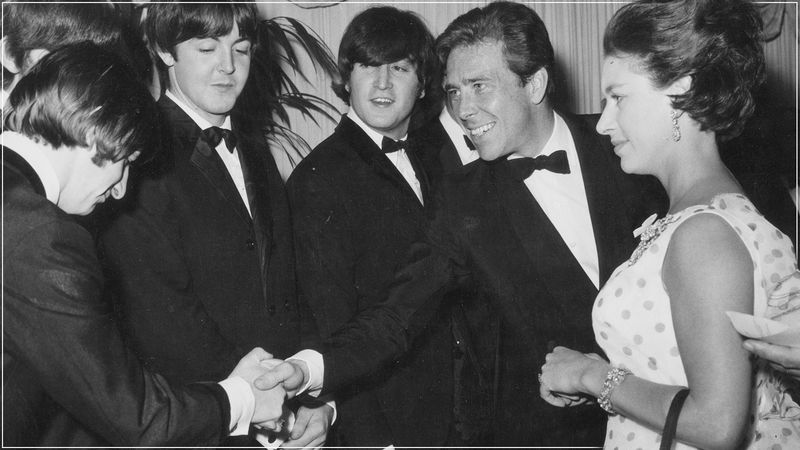

Lord Snowdon and Princess Margaret meet The Beatles at the premiere of Help!, The London Pavilion, 1965. Photograph by The Times

After university, he mixed the grand (he photographed the Queen, other members of the royal family and countless young aristocrats before he started working for Vogue) and the bohemian (he toured pubs in London’s East End, taking louche pictures of urban night life and, according to one eagle-eyed commentator, was once seen on a dawn bus, dressed in black leather and carrying a whip). And it was to the East End that he returned in the late 1950s when wooing Princess Margaret; he rented a discreet flat in Rotherhithe, overlooking the Thames, to which he would whirl the Princess on the back of his Norton and where she would “fry him sausages and things”.

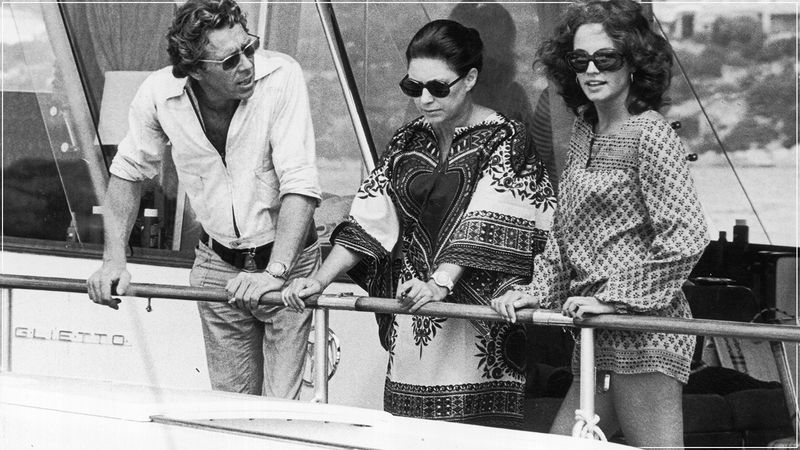

Once married, the Snowdons became flamboyant (and exquisitely dressed) members of the bon ton, holidaying in Rome, visiting the Aga Khan in Sardinia and the Arizona ranch of Mr Lewis Douglas, the post-war American ambassador to London – his daughter, Ms “Charming” Sharman Douglas, was one of the Princess’s closest friends and the giver of “dazzling” parties at the embassy.

From left: Lord Snowdon, Princess Margaret and Princess Salimah Aga Khan, Sardinia, Italy, c. 1970. Photograph by Camera Press

In London, theirs was a fast set that included such luminaries as Mr Peter Cook, various Rolling Stones and Beatles, dancers Mr Rudolf Nureyev (who was always in and out of Kensington Palace “in skintight black leather”) and Ms Margot Fonteyn, theatre critic Mr Kenneth Tynan and comic actor Mr Peter Sellers, the latter two of whom wore beautiful suits by tailor to the stars Mr Doug Hayward. Lord Snowdon and Mr Sellers made a short film for the Queen’s 39th birthday – she was amused. Ms Margot Fonteyn gave the Earl a pre-Columbian gold charm of an eagle with spread wings, which he wore throughout his life.

And Mr Cook saved the day when Mr Tynan gave a dinner party at which the Snowdons and other guests were treated to a digestif of blue movies: Mr Jean Genet’s Un chant d’amour, which contained full frontal male nudes, was greeted with particular frostiness, until Mr Cook started to talk over the images, “treating the movie as if it were a long commercial for Cadbury’s Milk Flake… Within five minutes, we were all helplessly rocking with laughter, Princess M included”.

Not all the Snowdons’ dinners were so frisky. The novelist Ms Angela Huth first met the Princess in 1962, at a dinner given by Sir Jocelyn Stevens (grandfather of Ms Cara Delevingne). It was, Miss Huth said, “a surprisingly informal occasion”; nonetheless the men wore dinner jackets and the women long dresses. “I remember borrowing a diamond brooch from a jeweller, lest I be underdressed.” The Earl, and his wardrobe, inhabited two distinct Londons.

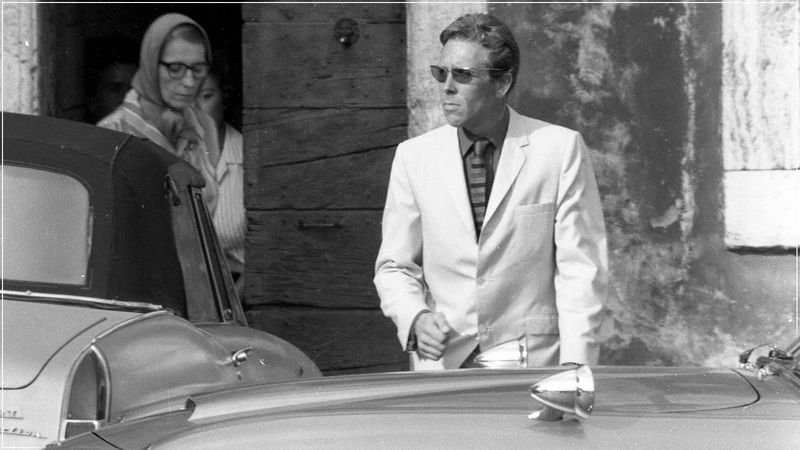

Lord Snowdon, Sardinia, Italy, 1966. Photograph by Sorci/Camera Press

Other hosts found the Snowdons tricky. The author Ms Drusilla Beyfus remembers that “She [Princess Margaret] and Tony were a glamorous couple [to have to dinner]. But there was a halo of anxiety about the way things would go. Because quite soon it was apparent they weren’t getting on very well.” The well-connected interior decorator Mr Nicky Haslam observed Lord Snowdon flicking lit matches at an annoyed Princess Margaret. The rows grew, as did the infidelities, on both sides. When photographs of the Princess’s dalliance with Mr Roddy Llewellyn were published in 1976, Lord Snowdon moved out of Kensington Palace. Divorce followed.

It was said of Lord Snowdon that he regarded a day without sex and a day without work as wasted. He certainly had many lovers, and several children. And he was certainly serious about all the work he took on, whether it be advising the Design Council, acting as provost of the Royal College of Art, designing an aviary for London Zoo or an electric wheelchair for the disabled, a group whose cause he constantly fought. His TV films won awards, though the one he made about “people of restricted growth” was seen by Princess Margaret as a little “too near home” – the Princess was 5ft 1in to the Earl’s 5ft 5in.

Lord Snowdon in Rome, 1965. Photograph by Sorci/Camera Press London

But it was for his photography that he was most celebrated. His documentary work could be stunning; a portfolio called Mental Hospital that he did in 1968 is both disturbing and compassionate. He was perhaps best known for portraits that ranged from Sir John Gielgud via Dame Iris Murdoch to Mr Damien Hirst, and in 2013 had a retrospective of his work at the National Portrait Gallery, which has more than 100 of his photographs in its permanent collection. His friendship with the royal family survived his divorce, and they continued to commission him – he took the Queen’s official 80th birthday portrait. He worked for The Sunday Telegraph and was a contributing photographer for Vogue for more than 60 years. He had sittings, not shoots: “Bang! Bang!” he’d go if anyone uttered the word. “I don’t want people to feel at ease,” he said. “You want a bit of edge.”

He knew what else he wanted, sartorially. At his Kensington studio, there was a stack of old blue shirts in an airing cupboard, their smell, his daughter Ms Frances von Hofmannsthal noted, “a cocktail of the tool cupboard and patchouli from the eau de cologne Zizanie”. Sitters would arrive in what they thought their best, and Lord Snowdon would hand them one of those old blue shirts; “Try this on, darling,” he would say. A blue shirt, he opined, is “a kind of uniform” of the sort he loved, and he staged an exhibition and published a book called Snowdon Blue, in which 61 stars wore a classic blue shirt. He was a classic himself. And a star.