THE JOURNAL

People say that the strangest thing about losing a limb is that you can still feel it: blood coursing through your veins; the tingling of imaginary skin; tendons tugging in a hand that’s no longer there. An itch you quite literally cannot scratch. These so-called “phantom limb” sensations can persist for years after amputation. “I can feel the blood pumping, pumping but it has no place to go,” says Mr Lamin Manneh, looking down at the space where his left arm used to be. “My hand is squeezing tight, but I can’t open it.” An ex-infantryman with the Irish Guards, he lost the limb, along with both of his legs above the knee, to an improvised explosive device (IED) in Afghanistan in 2010. Like many veterans who have suffered the loss of limbs, these feelings have made it difficult for him to sleep.

Mr Manneh’s injuries, while severe, are far from exceptional for soldiers of his generation. According to figures published by the Ministry of Defence, a total of 301 UK service personnel have suffered amputations as a result of injuries sustained in Afghanistan since the start of the British military campaign in 2001. And while this number includes servicemen who lost as little as a fingertip, it also includes many who, like Mr Manneh, lost much more. Of that number, 113 – more than a third – were classed as SMAs, or “significant multiple amputees”, which means they lost at least two hands or feet. Mr Manneh, who had the misfortune of being deployed to Afghanistan during the bloodiest phase of the campaign, was one of 38 SMAs recorded that year.

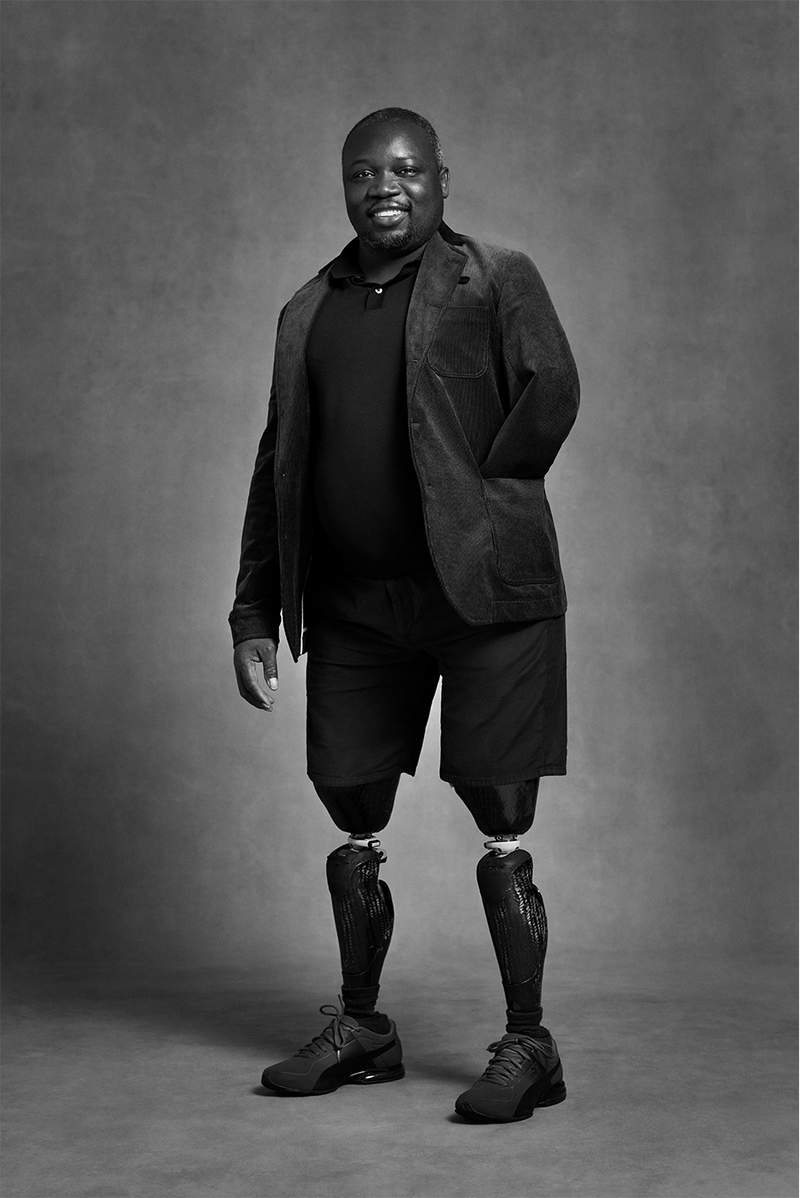

Along with phantom limb sensations, amputees might also be surprised to find themselves struggling to regulate their temperature. This symptom, unlike the eerie tingling of an invisible limb, is at least a little easier to explain. Just imagine your arms and legs as bars on a radiator, drawing heat away from your body and into the air around you. Lose a limb, and you lose your ability to stay cool. This is one of the reasons why, if you ever meet someone with a prosthetic leg, you shouldn’t be surprised to see them wearing shorts – even in the depths of winter. For many, this is a statement of pride; for others, it’s a heads-up to fellow pedestrians who might otherwise assume that they are fully able-bodied. But it’s often for the simple reason that if they weren’t wearing shorts, they’d be too hot. “Remembrance Day is the only day of the year that I wear trousers,” says Mr Andy Reid MBE, another amputee who stepped on an IED in Afghanistan in 2009.

Injured former servicemen endure symptoms like these on a daily basis. Not all of them have to deal with the debilitating consequences of losing a limb, like Messrs Manneh and Reid. But there are plenty of other, less visible injuries that can still have a lifelong impact. That’s to say nothing of the psychological trauma of warfare, which can be just as devastating and hard to shift. Humans are a ferociously adaptable species, but war can test even the most resilient of us. Without a support network to fall back on, these veterans can struggle to readjust to civilian life and are vulnerable to depression and anxiety. This is where people such as Ms Emma Willis MBE come in.

Ms Willis made the first of what would be many visits to Headley Court in 2008 after learning of its existence from a radio programme on the conflict in Afghanistan. This old Victorian mansion on the outskirts of London was then the site of the British Army’s medical rehabilitation centre, where soldiers wounded in the line of duty would receive treatment for what were often life-changing injuries. And it was running at full capacity. The designer and shirtmaker was moved to tears by the stories of these young men, who had joined the military out of a sense of patriotic duty only to see their careers cut short in the most horrific of circumstances. As she learned of the profound struggle they faced on their journey to recovery, she pledged to do whatever she could to help. And for a shirtmaker, the answer was obvious: make shirts.

The following year, Ms Willis founded Style For Soldiers to provide servicemen with bespoke shirts that were adapted for their injuries. In the case of amputees, breathable fabrics were chosen to help them stay cool, and cufflinks, which are near-impossible to fasten with one hand, were modified with Velcro. These shirts didn’t just provide injured veterans a much-needed confidence boost. They also helped them prepare for civilian life and the daunting prospect of re-entering the job market. Now in its 10th year, Style For Soldiers has grown far beyond its original remit. Along with providing bespoke shirts and walking sticks, it now arranges events such as a recent exhibition showcasing art and poetry created by former servicemen suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while its annual Christmas party is a highlight of the veterans’ calendar and has become the largest event of its kind.

Last month, in advance of the 2019 Christmas bash, MR PORTER was invited to dress, photograph and hear from some of the men that Style For Soldiers has helped over the years. It’s the first time we’ve done so since 2014, the year that British combat operations in Afghanistan officially ceased. A good occasion for a few old friends to get together and reminisce over war stories, it also served as a timely reminder that while the battle for these men may be over, the scars still remain; and the real story is what happens next.

Mr Andy Reid MBE

It’s rare that someone with injuries as severe as those suffered by Mr Andy Reid MBE can actually recall the moment itself. Most suffer from a bout of post-traumatic amnesia and wake up days, or even weeks, later in a hospital bed.

But Mr Reid remembers everything. The dust in his mouth; the temporary deafness caused by the blast; the futile attempts to self-medicate his wounds. “Right, I thought, I can’t see my legs,” he recalls. “Morphine, tourniquets. Morphine, tourniquets. I looked over at my left hand and there’s one finger hanging off, so I made a fist with the rest of my fingers to keep hold of it.”

This remarkable composure in the face of adversity is nothing less than is to be expected of Mr Reid, a man who embodies, almost to the point of comedic effect, the stoical, keep-calm-and-carry-on attitude we have learned to expect of a soldier.

Even as he lay in a hospital bed weeks later and listened to the doctor reel off his injuries – right leg amputated below the knee; left leg above the knee; right arm above the elbow – he was reminding himself that he was a survivor, not a victim. “There were other guys from my unit who were killed while I was in Afghanistan,” he says. “Out of respect for them and their families, I had to keep moving forward.”

To do that, he knew he needed to set himself goals. In the short term, to build up the physical mobility to leave Headley Court and go home for the weekend. In the medium term, to stand up and receive his Operational Service Medal at a ceremony in July 2010. And in the long term, to get down on one knee and propose to his girlfriend, Claire, and walk down the aisle with her. He achieved that last goal in September 2011.

“I’m a typical soldier,” he says. “I’m a proud man, an independent man. A lot of what I’ve achieved, I did so because I wanted to prove that I could. But I’m not so proud to say that I wouldn’t be where I am today if it hadn’t been for her. She’s the one who sees me at my worst. While I’m here getting pampered and having my photo taken, she’s at home keeping the family together.” It’s for this reason, he says, that events such as the Style For Soldiers Christmas party are as important for the spouses as they are for the veterans themselves.

It’s not just Christmas parties, either. An annual Style For Soldiers day out at Woburn Safari Park in the summer also allows former servicemen the rare opportunity to bring their entire families – a rare chance, says Mr Reid, for children with injured parents to meet each other. “My seven-year-old son, William, is the only boy in school whose dad’s got one arm. Who does he talk to about that? His friends can’t relate. When all of their dads have taught them how to tie their laces, they don’t understand why he’s still wearing Velcro shoes.

“It’s like throwing a stone into a pond,” he says of the effects of his injuries. “The ripples affect everyone around me; they all need embracing, too.”

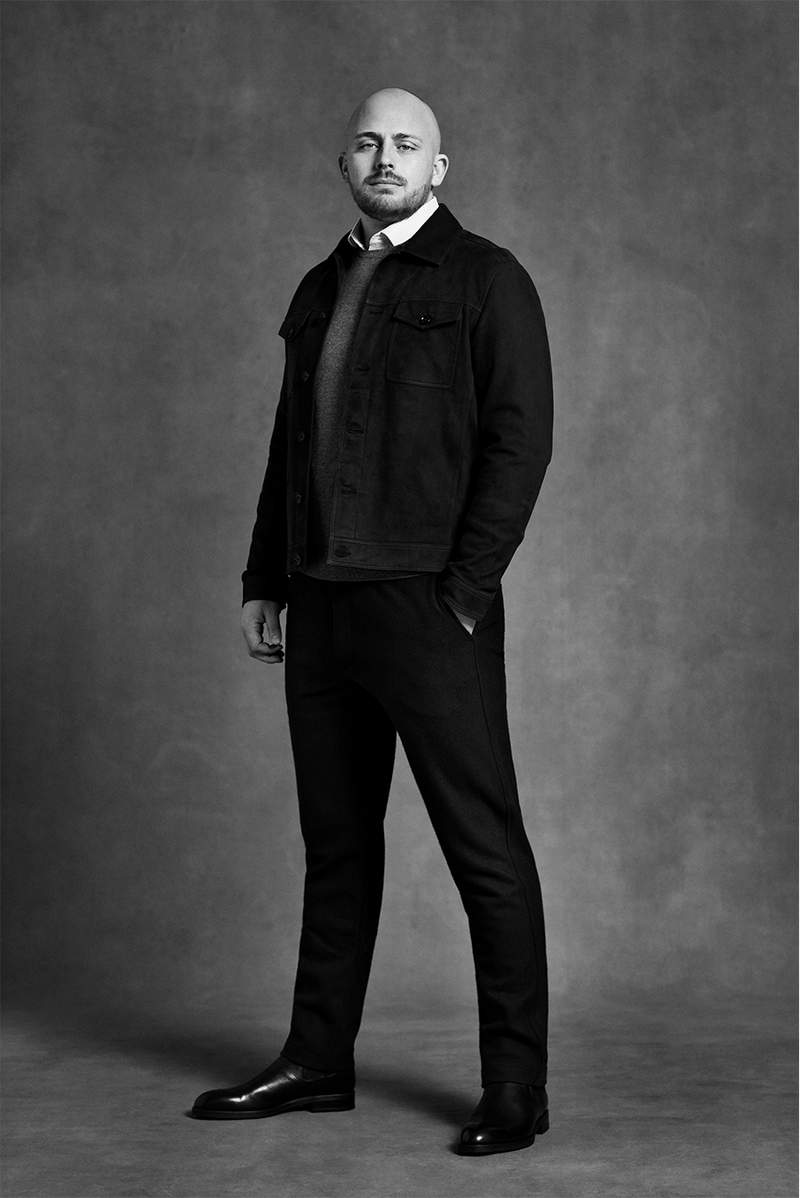

Mr Richard Gamble

Not all soldiers medically discharged from the military are injured during operational duty. Some receive their injuries in a rather less dramatic fashion. In a sense, though, it doesn’t really matter whether you were hit by a piece of shrapnel or by a piece of falling machinery, or even if you just fell over. The end result is much the same: you lose your job, lose your sense of identity and acquire a set of physical problems that can last a lifetime.

Former Lance Corporal Richard Gamble joined the Royal Engineers straight from school at the age of 16. “I was on a difficult path, to say the least,” he says. “I decided to join the army to get back on the straight and narrow.” Despite his intentions to serve a long career – “that was my life until 42” – it was cut short after he picked up a persistent leg injury that deteriorated to the point that his legs would collapse beneath him.

He was diagnosed at first with popliteal artery entrapment syndrome, a crushing of the main artery in the leg, and, a year later, with chronic compartment syndrome. Shortly after this second diagnosis, he was discharged from the military. “It all happened suddenly,” he says. “I wasn’t prepared. I was informed that I was going for an occupational health meeting on Monday morning, turned up and lost my job right there and then.”

He felt bitter for a long time about the way it was handled. “It made me realise that I was just a number,” he says. At first, the process of buying a new house was able to distract him. But over the next couple of years, his mental health took a turn for the worse. “I shut myself off,” he says. “I stopped socialising. I deleted all my old army friends off Facebook because I couldn’t stand to watch them as they progressed in their careers.”

Things came to a head in late 2017. “I had a panic attack in the kitchen and walked to the train station. I sat on the platform and waited for the next train to come so I could throw myself in front of it. My mind was set, but my wife somehow knew where I was going. The police arrived and took me to the station. That’s where I first started talking.”

In the two years since being diagnosed with depression and severe anxiety, Mr Gamble has competed at the Invictus Games in Sydney as part of the swimming team. “It’s something I’ve always loved,” he says. He has also become better at accepting help. “It’s a slow process, breaking down that facade of masculinity. Just holding your hand up and saying, ‘I’m having a bad day’ can be the hardest thing to do.”

He’s ready to close the book on his military career – but with more surgeries on his legs, he’s finding it hard to move on. “I just don’t know what the next five years hold,” he says. “When I joined the army at 16, I didn’t want to do anything else. Now I feel like I’m that teenage boy again. Only this time I’ve got a family, a mortgage, kids. It was exciting then. It’s daunting now.”

Mr Louis Farrell

Former Lance Corporal Louis Farrell served 13 years in the armed forces, joining straight out of school at 16 and leaving at 29. During his career as an aviation engineer, he was based in Germany, trained in France, the Czech Republic and the US, and completed a tour in Afghanistan. “Join the army, see the world,” he says. “It’s a bit of a cliché but it’s true.”

The accident that ultimately led to the loss of his leg occurred while on tour in Northern Ireland in 2013. It would be another five years and 12 operations before the limb was finally amputated. “I got it stuck beneath a piece of kit. It didn’t seem like a catastrophic injury at first; there wasn’t blood everywhere. I assumed that it’d be a quick recovery. But I never walked properly on that leg again.”

He suffered severe nerve damage from the accident and was diagnosed with chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Various procedures to correct it failed, including nerve grafts, a Z-plasty procedure to lengthen his Achilles tendon and even a spinal-cord stimulator implanted under his skin.

One year, while on holiday in the Dominican Republic, he found himself unable to dance with his daughter at a family merengue night. Another father, who he had met earlier in the week, offered to dance with her instead. “I just sat there by the dancefloor, stewing,” he says. “I was heartbroken.”

Under normal circumstances, asking a surgeon to remove one of your legs would be an incredibly difficult decision; but after years of chronic pain and limited mobility, compounded by the fact that his injury was now limiting his abilities as a father, Mr Farrell’s mind was more than made up. “That was the moment I decided I’d had enough,” he says.

That’s not to suggest, however, that he found it easy. “You develop insecurities,” he says. “You don’t show it outwardly, but you do start to wonder if you’re still seen as attractive.” To make matters worse, his pain medication had caused him to balloon in weight, meaning that his clothes were no longer fitting properly.

“When you talk to Emma, she writes off the idea behind Style For Soldiers as nothing more than a simple act of kindness,” says Mr Farrell, who left the military in May of last year and is now training to become a commercial pilot. “But it’s so much more than that.

“As soldiers, we take pride in our appearance; being smartly turned out is part of our job. But when I interviewed with the airline, I was a former Lance Corporal. I didn’t have the money to buy nice clothes; I didn’t feel sure of myself at all. Having a proper shirt to wear made a big difference.”

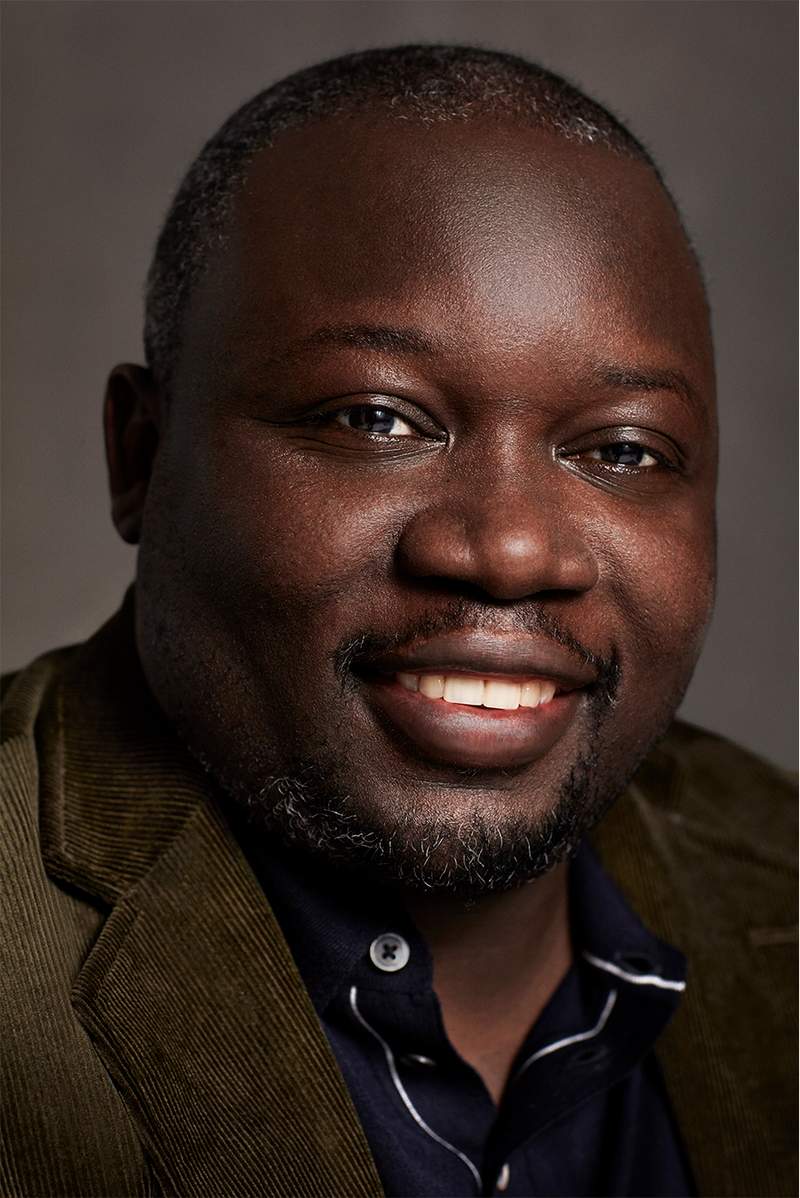

Mr Lamin Manneh

Mr Lamin Manneh hails from the seaside town of Brufut in the Gambia, a small country in Western Africa whose borders follow the Gambia River as it snakes westwards to the Atlantic Ocean. Once a colony of the British Empire, the Gambia is now a member of the Commonwealth, through which its citizens are eligible to enrol in the British Armed Forces – something Mr Manneh decided to do in 2006.

“People from Gambia have been fighting with the British since the WWI,” he says. “When they come back from tour, they tell stories. As a young man, all I wanted was to be a part of something bigger than myself, and so these stories inspired me.” After a lengthy application process that involved relocating his family to the UK, he was finally enlisted in 2009, joining the First Battalion of the Irish Guards.

The following year, while on patrol in Helmand Province in Afghanistan, he stepped on an IED. He was considered incredibly lucky to survive the blast, which caused the loss of both of his legs above the knee and his left arm.

Like many victims of traumatic injuries, he remembers very little of the moment itself; he was put into an induced coma and came round two weeks later in a military hospital in England with his wife by his side. “I was confused at first because I thought I was still in Afghanistan,” he remembers. “I said to her, ‘What are you doing? Who brought you here?’”

Mr Manneh struggled to come to terms with the loss of his limbs. “I thought, that’s it. It’s over. I’m worthless now. I won’t be able to look after my wife or my kids. As an African, it’s my obligation to look after my parents, too. So, I wasn’t able to be a father, a husband or a son. I felt that if I had just died there, I wouldn’t have had any of these worries. But God said, ‘No. I’ve got a better plan for you.’”

He found comfort in his faith in Islam. “As Muslims, we’re taught to believe in destiny,” he says. “If you see your journey leading you somewhere you didn’t expect, you say: ‘You know what? This is my life. I can’t complain.’ If I did, I would be a very ungrateful man.”

In the nine years since receiving his injuries, Mr Manneh has reinvented himself as a multi-disciplinary para-athlete, competing at the Invictus Games and picking up medals in the shot put, rowing and discus events. He regularly plays sitting volleyball. He lives in Greater Manchester with his wife and five kids on a street of specially adapted houses nicknamed “Veterans’ Village”.

Mr Stewart Hill

Mr Stewart Hill’s 18-year career in the military came to an end on a hot summer day in July 2009 in Helmand Province, Afghanistan. It was a day that had a profound effect on many lives, not just his own.

Mr Hill, then Major Hill, was overseeing the extraction by helicopter of two of his soldiers, one of them injured and the other deceased, when another one of his soldiers, Lance Corporal David Dennis, stepped on a huge IED just a few metres away from him. The ground was baked rock-hard by the sun; the blast left a crater in it big enough to fit a small car.

Lance Corporal Dennis was found 40 metres from the blast and barely alive by one of his squadmates, Lance Sergeant Dan Collins, who stayed by his side until he died. The following day, Lance Sergeant Collins also watched as one of his best friends died in another IED blast. Wracked by PTSD and survivor’s guilt, he hanged himself a year later at the age of 29.

“The damage of war reverberates,” says Mr Hill as he recounts the events of that day. “It’s not just those directly affected. It’s their families, their friends. Anyone touched by or connected to that person.”

It’s tempting to say that Mr Hill got off lightly, all things considered. He remains fully able-bodied; indeed, he doesn’t appear to have been injured at all. The army medics thought as much, too, as they transferred him by helicopter from the blast site to the British Army air base at the former Camp Bastion.

But his condition began to deteriorate rapidly, and as they checked him over again, they found a small wound in the back of his head. Two pieces of shrapnel had penetrated his skull and come to rest just millimetres from his brain stem. He was put in an induced coma and flown back to the UK, where he spent four weeks in hospital.

The surgeons were able to keep him alive, but he did not make a full recovery. The shockwaves caused by the shrapnel had passed through his brain and done permanent damage to the right frontal cortex, the area responsible for what’s known as executive function.

This is our ability to make plans, remember instructions and directions, prioritise and multi-task. “Making a cup of tea now required massive concentration,” he says. “I quickly realised that I no longer had the capacity to complete tasks at a level that’s required for work.”

Mr Hill was medically discharged from the military in 2012. He tried holding down a part-time job and attempted an Open University course, but couldn’t manage either. Unsure of what to do next, struggling with his loss of identity as a soldier and encumbered with the responsibilities of adult life, he found himself at a low ebb.

Shortly thereafter, inspired by a chance encounter with an artist while on holiday in Mallorca, he rediscovered his childhood passion for painting and began to pour his heart out onto the canvas. “Through that process, I opened my mind to seeing things, and my life, from a different perspective,” he says.

Mr Hill’s oil paintings have since been featured in an exhibition called Art In The Aftermath, which was organised by Style For Soldiers as part of its wider work in helping ex-servicemen come to terms with and articulate their experience of war. He speaks highly of Ms Willis, the charity and the injured veterans’ community in general.

“There’s a great compassion in the community because of the awareness of suffering,” he says, quoting Mr Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables: “Great perils have this beauty, that they bring to light the fraternity of strangers.”

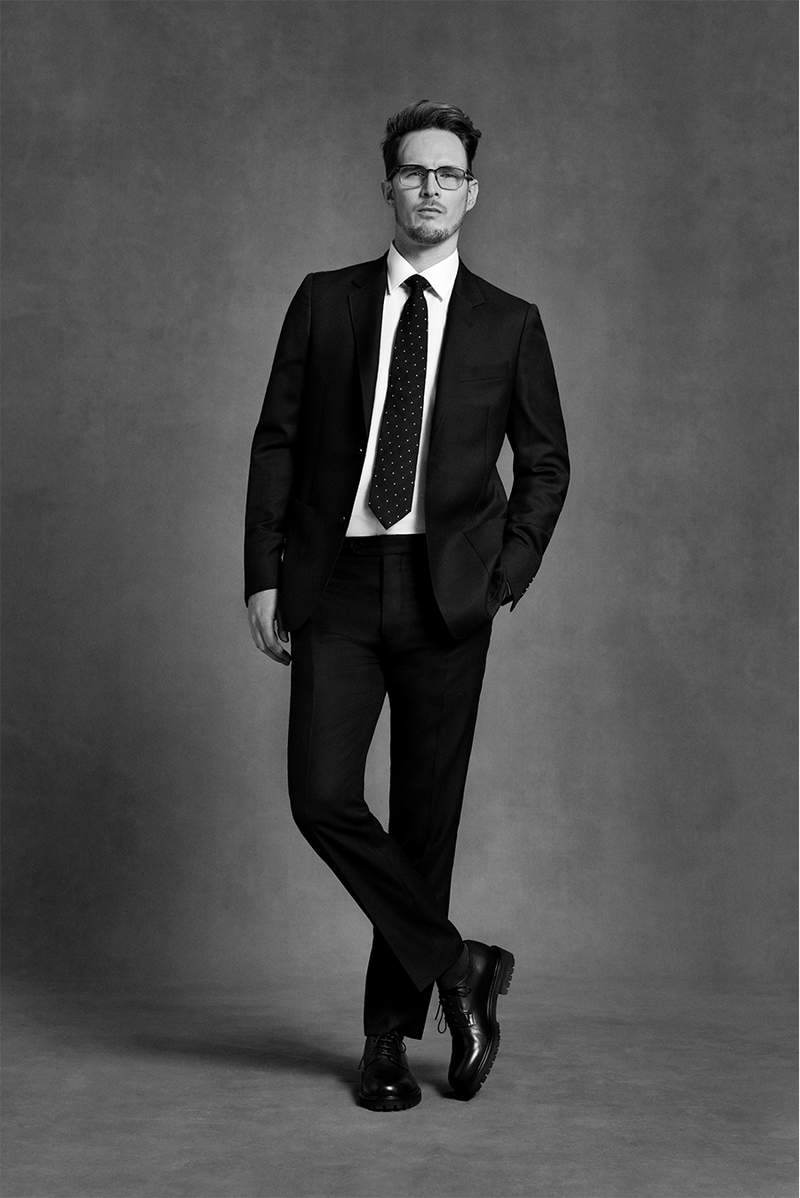

Mr David O'Mahoney

Mr David O’Mahoney never quite made it to Afghanistan. A household cavalryman garrisoned at Hyde Park Barracks in London, he was completing the 18-month ceremonial duties that preceded his first operational tour when he was injured in 2011. It wasn’t a bullet or a roadside bomb, but that most English of hazards: a black taxicab.

He had been attending a military boxing event at the Royal Albert Hall and was on his way back to the barracks when he was struck by the taxi and dragged under its wheels. “My head and body were lodged into the wheel arch,” says Mr O’Mahoney, recounting second-hand information passed onto him by colleagues who attended to him at the scene. (He remembers nothing of the event.) “One of them, Corporal Major Ireland, said that in all the things he’d seen in Afghanistan and Iraq, he’d never seen so much blood.”

He was kept in a coma for four weeks at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, east London, as doctors attempted to alleviate the pressure caused by a bleed on his brain. They were eventually forced to operate on him to remove nearly half of his skull. “The surgeons told my family to say their goodbyes,” he says. “They said that even if I did survive the operation and they managed to bring me round, I’d likely be in a vegetative state for the rest of my life. But I woke from the coma kicking and screaming. The first thing I did was ask the surgeon why he’d only shaved one half of my head.”

His remarkable recovery and indomitable spirit saw him chosen to raise the flag at the Paralympic Games in London in 2012, a day he remembers as the proudest of his life. Not long after that, however, he suffered a suspected seizure and was medically discharged from the military.

“I didn’t realise it at the time, but I’d been suffering with depression and anxiety since the accident,” he says. “It was little things, like using alcohol and gambling as a way to cope. And when I was discharged and lost my identity as a soldier, things took a turn for the worse.”

Before joining the army, Mr O’Mahoney had endured a difficult upbringing. “We moved to five different homes in five different parts of London. Every time we moved home, I moved school,” he says. “By the time I was in my early twenties, one of my closest friends was in prison for murder, my brother was facing a firearms charge, and the few friends I had left were either drug dealers or recreational users.”

The military had introduced structure and discipline into his life where it was sorely lacking. It had provided him with the strong male role models who had been so absent in his youth. Above all, it had endowed him a sense of purpose and identity. And then, just like that, it had all been snatched away.

“I started to have suicidal thoughts,” he says. “Getting out of the shower and seeing my bathrobe, a voice in my head would say: ‘Just take the belt and place it around your neck. See what it’d feel like. Hang it from your wardrobe. See what it would look like.’ That scared me, because I began to understand the power of the human subconscious. I don’t believe that anyone in sound mind takes their own life. But how long until my brain convinces me to try?”

Eventually, through sessions with a neuropsychologist organised by the lawyers representing him in his accident, he managed to turn his life around. “I began to keep a gratitude journal. I started educating myself in sleep hygiene and mindfulness. And after a while, things began to change. People started to treat me differently. New opportunities started appearing. Then, an offer to speak at an event popped up.”

Mr O’Mahoney, an eloquent and well-dressed man, has since launched a new career as a motivational speaker.