THE JOURNAL

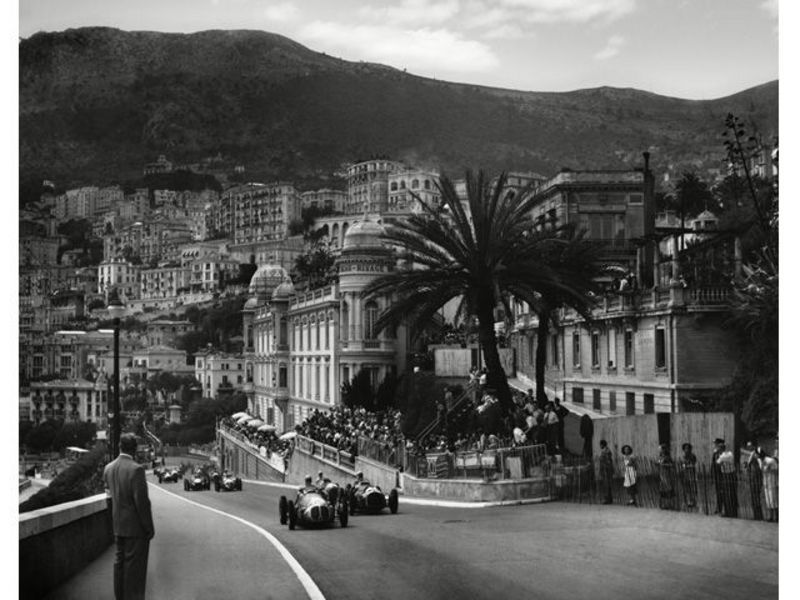

Sir Stirling Moss leading the pack in a Maserati 250F at the Monte Carlo Grand Prix, 1956 LAT Photographic/ Rex Features

As the renowned car manufacturer marks its centenary, and premieres the Alfieri coupé, we look at the crash-laden story of its six founding siblings.

To race cars in the 1920s took a demonic madness. Your risk of going up in flames in your supercharged tube of sheet metal was roughly that of a witch in 17th-century Massachusetts. The few men who chose this as their deranged pursuit possessed the Yin of precision engineers and the death-wish Yang of bronco riders. And nowhere could you find more of them than in the slender arc of northern Italy between Bologna and Turin.

This is the “other” Italy, not the one of soft living and sunshine, but a misty, toilsome land. At one end is Turin, home to Fiat, the greatest of Italy’s industrial giants. At the other are Parma and Bologna, the centres of Italy’s food industry. In between are towns such as Modena, home of Ferrari, and Voghera, where between 1881 and 1898 Mr Rodolfo and Ms Carolina Maserati raised six boys: Carlo, Bindo, Alfieri, Mario, Ettore and Ernesto.

From left: Messrs Bindo, Ettore, Ernesto and Mario Maserati outside the Officine Alfieri Maserati premises in Pontevecchio, Bologna, circa 1934 Spitzley/ Zagari

The history of cars is filled with gigantic individuals, behemoths such as Mr Henry Ford and Mr Enzo Ferrari, and protean geniuses such as Mr Colin Chapman of Lotus. And then there are the Maserati brothers: quiet, brooding figures who stand at the entrance to Italian automotive history. They did not preen and threaten like their neighbour and rival, Ferrari. Their obsession with cars was complete, their interest in the business of cars ambivalent.

By the time Maserati began making production road cars, the brothers were long gone from the company they founded. But their spirit lived on in a series of tough, gorgeous designs adored by mechanical purists and rock stars alike. When Mr Joe Walsh needed a car to symbolise the decadent rock life of 1970s California in his song “Life’s Been Good”, it had to be a Maserati.

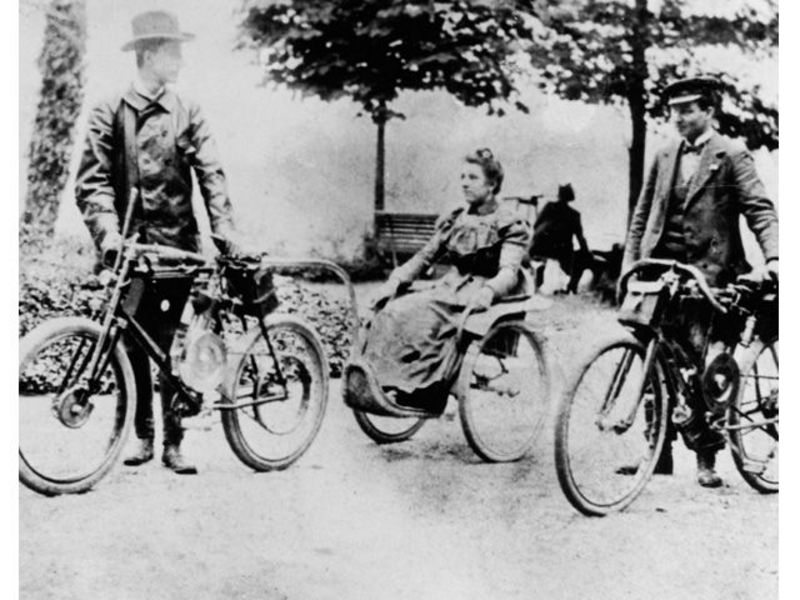

Marchese Michele Carcano and Mr Carlo Maserati with Carlo’s first designs at Anzano del Parco, Como, 1898 National Motor Museum/ Heritage Images/ Getty Images

This year, Maserati is marking its centenary at a moment when its fortunes are surging again as part of Fiat. The Ghiblis and Quattroportes currently clog the best-heeled streets of Mayfair and Manhattan, and the company has recently premiered what should be the most coveted thruster of 2016 – the absurdly gorgeous Alfieri coupé. But it is also a reminder of how unusual this company is and the story of the extraordinary men that built it.

The Maserati brothers’ father, Mr Rodolfo Maserati, was a train driver and engineer who shared his mechanical interests with his sons. The eldest, Carlo, was a prodigy. As a child he built working model steam engines and at the age of 17 designed and built his own motorcycle, a four-stroke single-cylinder petrol engine mounted on a reinforced bicycle frame. His talent was spotted by a local nobleman, the Marchese Michele Carcano, who offered to pay for the manufacture of Carlo’s motorcycle design. Two years later, Carlo won his first race, a 35-mile scramble from Brescia to Orzinuovi, against a Wacky Races-worthy cast of cars and other motorcycles. Italy’s automotive world was small at the time, and Carlo was soon hired by Fiat to become head of its testing department.

The Maserati factory in Modena, pictured in 1958 Courtesy Maserati S.p.A

Bindo and Alfieri followed him into the industry, taking jobs at the Isotta Fraschini company in Turin as testers. But in 1910, Carlo was taken ill, and died. The trauma tore at the family. Alfieri, the most like Carlo in terms of his intelligence and passion for cars, and the then 16-year-old Ettore, left Italy to work for Isotta Fraschini in Argentina. Mario, the only one of the brothers not fascinated by engineering, plunged himself into his chosen love: painting. Bindo, now the eldest and by temperament the most conservative of the brothers, was determined to rise through the ranks at Isotta and stayed apart from his brothers’ affairs.

Alfieri and Ettore returned to Italy on the eve of WWI in 1913. Alfieri had decided to pick up Carlo’s legacy and opened his own garage business in Bologna. During the war, Bindo, Alfieri and Ettore all worked on aeroplane engines for Isotta. But Alfieri, a driven entrepreneur, also designed and manufactured his own line of spark plugs at his Bologna workshop.

“Ernesto, the youngest brother and easily the best driver in the family, was given the keys to the Tipo 26, and in the summer of 1926 he drove it 104mph to win its first race in Bologna”

The end of the war unleashed Alfieri and Ettore’s pent-up energy. Their youngest brother, Ernesto, was soon old enough to join them and he turned out to be the best driver of them all, slightly built and lightning fast behind the wheel. Supported by Isotta, Alfieri designed his first two-seater racing car and started to win road races in northern Italy. His cars caught the attention of a local railway manufacturer, Diatto, which also made a dreary line of touring cars. Alfieri was recruited to create a racing version of these cars, and in the early 1920s he drove his Diattos in Grand Prix races. Despite having a fraction of the resources of his racing rivals, such as Bugatti, Delage and Sunbeam, Alfieri managed to drive his Diattos into contention.

In 1926, with the financial support of the Marquis Diego de Sterlich, one of the wealthy, gentleman drivers of the time, the Maserati brothers produced their first car under their own name, the Tipo 26. It was a sleek, aluminium tube with a 1,500cc engine, painted Italian racing red. Mario’s painting skills had been called on to produce a logo for the new Maserati race car. It was a trident, the symbol of Bologna, painted in red and blue, the city’s colours.

The Maserati trident logo designed by Mr Mario Maserati, 1920 Courtesy Maserati S.p.A

Ernesto, the youngest brother and easily the best driver in the family, was given the keys to the Tipo 26, and in the summer of 1926 he drove it 104mph to win its first race in Bologna. Orders for Maseratis began to spike. And in 1929, a Maserati V4 with a 16-cylinder engine set a world record for a 10km race, averaging 153mph in Cremona. The next year, a Maserati won its first Grand Prix in Tripoli, and began consistently beating the cars produced by Ferrari, Alfa Romeo and Mercedes.

Motor racing at the time was beyond treacherous. At the Italian Grand Prix of 1928 at Monza, the Maseratis’ great friend and rival Mr Emilio Materassi collided with a Bugatti, spun into the crowd and was killed along with 22 spectators. Ernesto came sixth. Crashes and deaths occurred with appalling frequency. During the Mille Miglia road race of 1930, a year in which Maseratis won seven major races, the Maserati driver Mr Luigi Arcangeli spun off a mountain road when his brakes failed. He was fortunate to survive.

Mr Tazio Nuvolari driving a Maserati 8CM to victory at the Nice Grand Prix, 1933 Rex Features

So it must have been more of a shock than a surprise when, in 1927, Alfieri lost a kidney following an accident during a race in Messina, Sicily. In 1932, when his second kidney failed, doctors could not save him. After he died, Bindo, the most corporate and conservative of the brothers, rejoined the company as chairman, while Ernesto was put in charge of the technical side.

In competition, Maserati continued to thrive. In 1933, Mr Tazio Nuvolari, a dashing Italian driver known as “The Flying Mantuan” and described by Mr Ferdinand Porsche as “the greatest driver of the past, the present, and the future”, fell out with Mr Ferrari and decided to drive a Maserati instead. He won a string of races, including Grand Prix in Belgium and Nice, and raised the marque’s reputation even further. But this was not enough to combat the might of the Third Reich, which supplied Mercedes and Auto Union with orders and ample funds to dominate European motor racing. The gear-heads of Bologna would struggle to compete.

“Motor racing at the time was beyond treacherous. Crashes and deaths occurred with appalling frequency”

Ernesto, Ettore and Bindo decided to sell Maserati to the Italian industrial entrepreneur, Mr Adolfo Orsi. Mr Orsi took care of the finances, the Maseratis took care of the cars and in 1939 and 1940, the American driver, Mr Wilbur Shaw, won the Indianapolis 500 in a Maserati 8CTF.

From 1940 to 1945, the new Maserati plant in Modena, Mr Orsi’s base, built batteries and spark plugs for Italy’s war effort. The experience drained the Maserati brothers of any lingering desire to be part of a vast industrial enterprise. They wanted to return to where they had been, building cars from scratch.

Mr José Froilán González driving a Maserati 4CLT/48, and Mr Luigi Villoresi in a Ferrari 125, lead the pack at the Monaco Grand Prix, 1950 Rex Features

In 1946 they won the Nice Grand Prix, an exclamation point on the end of the war, and unveiled the Maserati A6. The A stood for Alfieri, the 6 for the number of cylinders in the engine. It was the first Maserati designed for mass production, and soon evolved into the Pininfarina-designed A6-1500. Every Italian sports car we see on the roads today can be traced back to this car.

There would be many more successes for the Maserati name. In 1957, Mr Juan Manuel Fangio won his fifth Formula One championship at the wheel of a Maserati. Its cars would soon go on to their greatest commercial success. But the Maserati brothers were long gone. Ettore, Ernesto and Bindo left the company in 1947 when their 10-year contract with Mr Orsi expired. They returned to Bologna, where they had opened their first workshop. For the next 20 years, they built sports cars under the name O.S.C.A.

It had never been their goal to be the biggest, most brazen Italian car makers. They could leave that kind of ambition to their neighbour, Mr Ferrari. Family and quality of work were more important. As Maserati champion Mr Fangio noted in Mr Tony Howard’s 1984 book Countdown to a Grand Prix, “First of all you need great passion, because everything you do with great pleasure you do well.”