THE JOURNAL

The history of our interaction with books, as depicted in art.

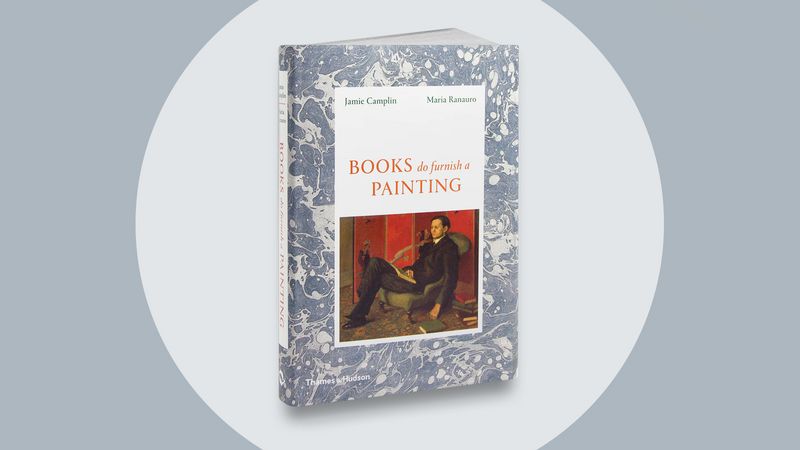

What is a book? Who invented the artist? Why do artists love books? In our post-truth world, is print dying out? And what does this all mean for the future? Don’t worry, we’re not having some sort of existential crisis here – instead we are delving into the symbiotic worlds of literature and art in Books Do Furnish A Painting, which is, as you could probably surmise, a history of books in paintings. Written by Mr Jamie Camplin and Ms Maria Ranauro, this charming illustrated study provides answers for the above questions in the process and, most interestingly, gives us a new frame of interpretation through which to chart the development of Western society.

Books in the 21st century are treated as an endangered species: a dying art form superseded in the digital age by everything becoming accessible instead through smartphone and Kindle screens. But what this book aims to illustrate, through a curated selection of celebrated Western artworks, is that our interactions with books during the last 500 years are more symbolic than we might think, and are therefore unlikely to be completely replaced.

Starting at the (almost) very beginning in the life of literature, Books Do Furnish A Painting traces the history of the printed book – from codices and compendiums through to the novels and tomes we read today. The first books in Western society were religious texts or theological discourses, and the depictions of books in early European art are pretty much exclusively pictures of devotion or penance: figures studiously studying theology, the Virgin Mary reading the Bible, Mary Magdalene searching for forgiveness. The 18th and 19th centuries saw the rise of the professional writer and an increase in demand for novels – triggered in part due to preoccupations with self-betterment and self-love. The artworks of this era that featured books reflect the push for modernity as books became a staple of middle classes – who, as Mr Camplin writes, “could recognise themselves while being entertained” and used them to “parade bourgeois values and virtues”. (See the below painting by French artist Mr Roger de la Fresnaye, a member of the Section d’Or group).

“Married Life” (1912) by Mr Roger de la Fresnaye. Photograph by Minneapolis Institute of Art, courtesy of Thames & Hudson

The paintings in this study – by artists from Mr Edgar Ainsworth to Messrs Sandro Botticelli and Paul Cézanne – show books as props used to depict the most human of experiences. They illustrate our changing religious beliefs, our relationships with each other and the world around us and what society believes about friendship, sex, love, gender, politics, education, morality and theology. They are used as a source of comfort, a way to signify social status and a means for expanding knowledge or pleasure. As Mr Camplin writes, “Happy or sad, no reader of a book, or painter of a book, ever forgot that they were human.”

But what about now, in the digital, post-truth world we live in? Do physical books still have the same significance? Mr Camplin posits thus: “It’s no accident that instant methods of communication, giving no value to accuracy or truth, have no longevity, especially if they have no physical existence.” His argument is that there are no famous paintings featuring computers and phones, despite their ubiquity. Just as people revert to vinyl, to shooting photographs on film as we look to the past in a nostalgic search for something “real”, it would appear that the appetite for physical texts is also on the rise. According to figures released by The Publishers Association earlier this year, 2017 saw record-breaking figures for publishers as book sales incomes in the UK increased by five per cent on the previous year, with a 31 per cent rise in hardback sales. Mr Camplin says, “Artists and writers are not about to be made redundant with the popularisation of virtual reality. Their creativity speaks to something deeper than technology can supply.” Let’s hope he’s right.

Buy the book

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up for our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences.