THE JOURNAL

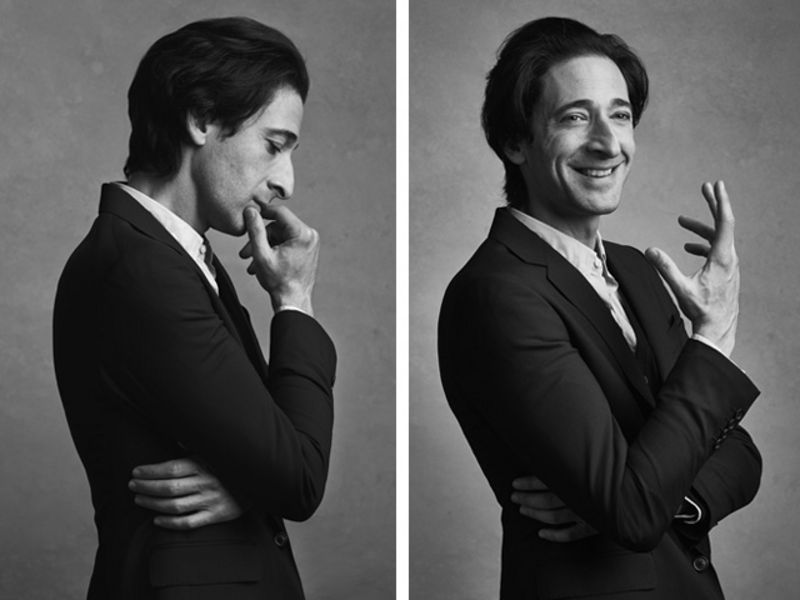

After being the youngest actor to win an Oscar, this prolific and elegant New Yorker is mulling life behind the camera.

Mr Adrien Brody is showing me how he used to perform magic, at age 11, for other kids’ birthday parties. “There’s a pattern, there’s a whole story you tell,” he says, picking up a sugar sachet from the table.

“You would take something and you would say, ‘I found this credit card on the floor and it has a woman’s name on it’” – he passes the sugar sachet from hand to hand – “‘Olivia Martinez... Olivia Martinez… maybe she lives downtown. I think she lives uptown, let me see... I would like to send this to her and I will send it to her telepathically…’ and then it’s gone” – he holds up his hands, empty, the sugar sachet gone.

“Whatever it is, you just keep making up something. You just have this trick, and that becomes your bit. You come up with a routine. You’re basically improvising.”

There’s lot of the street hustler to Mr Brody — a wily survival instinct born of his Queens background. But he grew up in front of the camera, in a sophisticated household. His mother, Ms Sylvia Plachy, is a New York-based photojournalist who for years had a weekly series in The Village Voice. Her son was a favourite subject. His father, Elliot, is a retired history professor. Mr Brody’s elegantly tapered looks, which have graced the catwalks in Milan for Prada, are wrapped around what he calls “immense willpower”. Last year alone, he shot five films. After finishing the role of Houdini for a TV miniseries in January, he filmed a supernatural thriller, Backtrack, in Australia; an Iranian political drama, Septembers of Shiraz, in Sofia, Bulgaria; a Jackie Chan comedy, Dragon Blade, in the Gobi Desert; and a film with the Kiwi director Mr Lee Tamahori, Emperor, in Prague; before finally returning to New York to shoot a noirish thriller, Manhattan Nocturne, which he also produced. He was working onset until 7am the day we were supposed to meet, and slept right through it.

“That’s not my style at all,” he says apologetically when we reconnoitre a day later for a late afternoon tea at The Mercer Hotel in SoHo. “I worked from 1 January to 1 January. I went from being beaten and tormented as a Persian Jew abducted during the fall of the Shah by the New Regime to, 48 hours later, fighting Jackie Chan in the Gobi Desert with a Jackie Chan stunt team. It was exhausting. I’m amazed that I’m functioning and able to carry on a conversation, I really am.”

“The fascinating element is the frailty of life, the flaw in the individual, but the beauty within that”

Ordering a pot of tea, he betrays no evidence of bleariness or burnout. The intensity he brings to roles is self-sustaining – a pure acting buzz pursued for its own sake. On screen, his spindly frame, gaunt good looks and steeply furrowed brow lend him an air of Chaplinesque vulnerability. He seems born to play starving artists. “The fascinating element is the frailty of life, the flaw in the individual, but the beauty within that,” he says. “That’s what I gravitate towards.”

He was a terrific Mr Salvador Dalí for Mr Woody Allen in Midnight in Paris, and last year excelled as the moustache-twirling villain in Mr Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, shot in Görlitz, on the eastern edge of Saxony. “You could walk to Poland for a shot of vodka,” says the actor of his third outing with Mr Anderson after The Darjeeling Limited and The Fantastic Mr Fox. “He has a troup,” says Mr Brody. “I was so thrilled when he brought me in and then we became good friends and developed a great friendship with Owen [Wilson] as well. Making Darjeeling was a wonderful life experience for me – travelling around India with these really fun, creative guys. There’s a lot of playfulness there, a lot of creativity. It’s special.”

Then, of course, there is his turn as Holocaust survivor Władysław Szpilman in Mr Roman Polanski’s 2002 film The Pianist, for which he won an Oscar – the youngest actor ever to do so. In many ways his career appears to have gone in reverse: the biggest acting gong in the land, usually marking the conclusion of a career, followed by a series of experimental roles for indie and first-time film-makers of the kind taken by actors looking to “break out”. “I feel as if I’ve confused people,” he says. “The perception was – because I was relatively young [when I won] and mostly working with independent film makers – ‘Wow, this guy came out of nowhere and skyrocketed.’ I have a lifetime of experience – I was the lead of a movie 26, 27 years ago. I’ve been on film sets my whole life. I know how to take care of myself.”

In the case of the Houdini miniseries, what drew him in was the chance to play an idol since childhood. The switch of obsessions, from magic to acting at age 12, was a small sideways step. “Not that acting was a macho profession or even a realistic career choice.”

“Whether you’re a hairdresser, or a delivery guy, or a bouncer, you’re still going to get beaten up... You’ve just got to pick your battles”

“Didn’t it get you beaten up?” I ask him. Woodhaven, Queens is not exactly Bloomsbury.

He laughs. “I got beaten up for other reasons, but yeah. You’re going to get beat up anyway. Whether you’re a hairdresser, or a delivery guy, or a bouncer, you’re still going to get beaten up; you’re still going to get hit in the head by somebody. You’ve just got to pick your battles.”

Excellent prep, it turned out, for the skirmishes and routs of Hollywood. There was the ignominy of seeing his part mostly cut from Mr Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line – “when the trades are saying Brody is going to star in The Thin Red Line, and you’re on the cover of Vanity Fair and then you’re not in the movie very much, there can be a backlash for an actor, clearly,” he points out, obviously still stung. Then, there has been the ongoing game of managing expectations post-Oscar. Scripts the quality of The Pianist have proved elusive, he says, although he has laboured to dispel any air of precocity, campaigning hard to secure the lead in Predators, Mr Robert Rodriguez’s reboot of the 1987 Schwarzenegger alien-shoot-em-up. He bulked up to 175 pounds for the role.

“My shoulder was almost the size of my head,” he says, “It was this major coup for me as an actor to be able to jump into a role like that. It wasn’t particularly lucrative. It wasn’t like, ‘this is the one I’m going to sell my soul for, please.’ The objective is to be as much of a chameleon as humanly possible.”

Winning an Oscar so young put him in the ring with an almost unwinnable expectations game. Hence his recent decision to get into the production side of the business and exercise more creative control. He’d like to direct, and sees his future through the view-finder he first bought while on the set of The Pianist to match Mr Polanski’s own.

“Acting really is elusive; no matter how much talent you have – at least for me, the process requires such discipline. Even with the discipline, there’s the potential that I won’t get to the place that I feel is good enough, that is connected enough, that is authentic to me, that I feel either the suffering or the joy or I’m transported from myself on set; that there’s this out-of-body experience. If you’re fortunate, and the camera and the focus-puller has it right, and you get it and the director incorporates it eloquently into the film, you give that magic on perpetuity. That’s beautiful. The audience sits there and they get hit with it like you did. That’s magic.”

Casting by SHO + CO