THE JOURNAL

Lessons in laid-back style from the sport that gave the world the blazer and the Henley shirt.

It’s early morning on the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. The sun has barely breached the horizon but boats are already gliding by to the clunk-splash of oars and the rhythmic swoosh of sliding seats. This is Boathouse Row, a historic stretch of riverbank on which you can find some of the oldest and most illustrious rowing clubs in the United States. For more than 150 years men have been rising before dawn to come here, braving darkness, rain and snow in pursuit of the perfect stroke.

Rowing is a sport that rewards obsession. Some sports find beauty in moments of brilliance, others in human drama. But in rowing it is found in precision and consistency. There’s no room for creative flair: mastering the sport means devoting yourself to the refinement of a single, repetitive motion. Catch, finish. Catch, finish. Rinse, repeat. But out of this repetition comes “swing”, that elusive and vaguely mystical state in which all the oarsmen are in the same groove and the sum becomes more than its parts. And there are few things more beautiful in all of sport than the sight of a boat being propelled through the water by a crew who are moving harmoniously.

Early starts aren’t all: rowing also demands physical fitness and mental strength. But as Mr Pete Seymour, one of the rowers we met on Boathouse Row, explains, “You get out what you put in.” For him, the excitement and stress of competition is matched only by the rush of euphoria you get when everything clicks – the feeling, he says, of “getting it right”. A born-and-raised Philadelphian, he attended college in Ohio and then Delaware before returning to his hometown and becoming a member of UBC, the University Barge Club, in 2005. One of Boathouse Row’s oldest clubs, UBC was founded in 1854 by 10 members of the University of Pennsylvania’s then freshman class.

For one of Mr Seymour’s crewmates, Mr Daren Frankel, the historic nature of the club is an incentive in itself. “We’re driven by the desire to be a part of something greater… a part of the tradition,” says the 24-year-old Cleveland native, who has to fit his training schedule around his day job as a technology consultant. Inside UBC’s clubhouse, located at numbers seven and eight on Boathouse Row, the tradition he’s talking about is palpable. The building, which in 1987 was designated a National Historic Landmark, is crammed with more than a century’s worth of rowing memorabilia. In the gym, high above the modern rowing machines, old collegiate banners hang from the ceiling; the walls are lined with trophies and shields inscribed with the names of long-dead oarsmen. It’s impossible to cross the threshold without feeling as if you’re walking in the footsteps of past generations.

Of course, it’s impossible to talk about rowing and its heritage without mentioning its relationship with men’s style. So much of the 20th and 21st century men’s wardrobe originated on the campuses and sports fields of American universities, and rowing has a rich history as a college sport: the Harvard-Yale Regatta, otherwise known as “The Race”, was first contested in 1852 and holds the title of the oldest intercollegiate sporting event in the US. But the sport’s greatest contribution to the world of men’s style came from the other side of the Atlantic, in the form of the blazer.

In his book, Rowing Blazers, Mr Jack Carlson traces the blazer’s origins back to the start of collegiate rowing itself, which began in earnest in the early 19th century on the waters of the Isis and the Cam, the rivers running through the English university towns of Oxford and Cambridge. Here it became fashionable to wear boating jackets in bold colours embroidered with collegiate heraldry. This was ostensibly to help spectators distinguish between crews during races – but it was at least partly for the purpose of peacocking, too.

It was one of these designs, a scarlet jacket worn by Lady Margaret Boat Club of St John’s College, Cambridge, that first gave rise to the term “blazer”, earning the nickname on account of its blazing red colour. It wasn’t long before the name lost its specific meaning and entered the mainstream lexicon. More than a century later, ostentatiously loud blazers are still to be found at boat clubs around the world – but it is the more sober navy-blue version that has gone on to become a staple of men’s style.

Elsewhere, it was Henley-on-Thames, a riverside town some 50 miles downstream of Oxford, that gave its name to another staple of the male wardrobe: the Henley shirt. This collarless polo shirt was the traditional uniform of boating crews rowing on this famous stretch of the river. A Mecca for rowers, Henley is home to the prestigious Henley Royal Regatta, a fixture on the British social calendar that runs for five days in early July and is perhaps the best-known rowing event in the world.

Back across the Atlantic, the name resonates. The University Barge Club of Philadelphia will be sending a boat to Henley for the regatta next month, and Mr Frankel wishes he were able to attend – but due to his time spent rowing for the Under-23 US team, he’s ineligible to compete in the club events. Mr Seymour attended in 2011, rowing in an eight-man boat. For him, as for many of the athletes who have rowed at Henley, it was the culmination of a long-held dream.

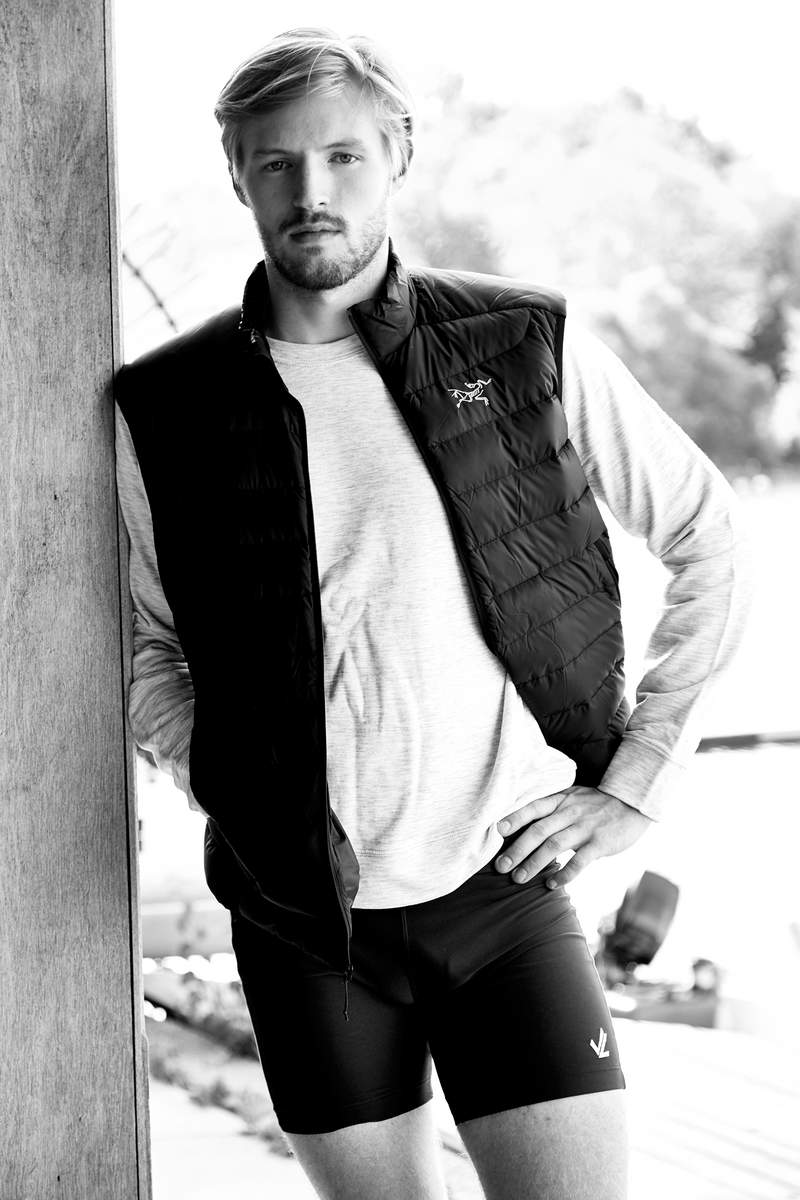

Outside of its marquee events, the modern sport of rowing is a decidedly laid-back affair, and rules regarding dress are kept to a minimum. As in any sport, form must follow function, and just as wooden oars and boat hulls were phased out long ago in favour of carbon fibre, doHenley shirts, blazers and flannel trousers have been replaced by Lycra all-in-ones and waterproof outerwear. But while concessions to performance are made, modern designers continue to be inspired by the sport’s colourful past. On the banks of the Schuylkill River, we tried out a few relaxed summer looks that mix the old with the new.