THE JOURNAL

MAAT Museum, Lisbon. Photograph by Hufton + Crow. Courtesy of AL\_A

From a pyramid in New York to a Death Star in Taipei – the new builds lighting up the horizon this year.

Austerity, Brexit, political disruption, financial crises, looming security concerns – you might think it wouldn’t be a good time for building. And yet they keep on coming. The long forecasted end of the architectural icon hasn’t quite happened and the megastructure, once only the dream of visionary modernists, appears to be alive and well.

The dollars generated by New York’s red-hot real estate market are funding whackier and bigger towers. Mr Rafael Viñoly’s stick-thin 432 Park Avenue is only the first of a new generation of “skinnyscrapers” – Lord Norman Foster’s and Mr Jean Nouvel’s are on their way and Danish architect Mr Bjarke Ingels’ VIA Building is a strikingly different addition to the Manhattan skyline. There are arts blockbusters, too. From Washington DC to Hamburg and from Lisbon to Taipei, architects are still experimenting with radical new homes for culture – bigger, bolder, sometimes even better. Often the best architectural interventions are small, carefully knitted into the existing fabric or the landscape. But if you’re going to go on an architectural pilgrimage, sometimes you need a sense of scale to justify the journey, a sense of being overwhelmed by something special. To help you do this, MR PORTER has scoured the globe to bring you the best new must-see buildings.

VIA 57 West, New York

Photographs by Mr Iwan Baan. Courtesy of BIG

Architect: BIG

Designed by Mr Bjarke Ingels – probably the world’s hippest architect right now, and also behind the new Google London headquarters – this striking tetrahedral (a 3D triangle) addition to Manhattan’s skyline has introduced a new, angular aesthetic to the West Side waterfront. Mr Ingels calls it a “courtscraper”, a cocktail of a European courtyard apartment block and a New York high-rise. It signals the arrival of the young (he’s 42) architect into the big time and Mr Ingels is about to make an even bigger splash in the city he now spends most of his time in. He’s designed a stacked and staggered tower on the World Trade Center site, a precinct police station and a spiralling skyscraper in the huge Hudson Yards development. For the moment, though, this theatrical, swooping structure on West 57th Street gives a flavour of architecture’s own disruptor. Look down on it from another tower and you can see quite how radical the sloping shape is, drawing attention away from the more conventional, straight-sided blocks around it, like a suicidal ski-slope.

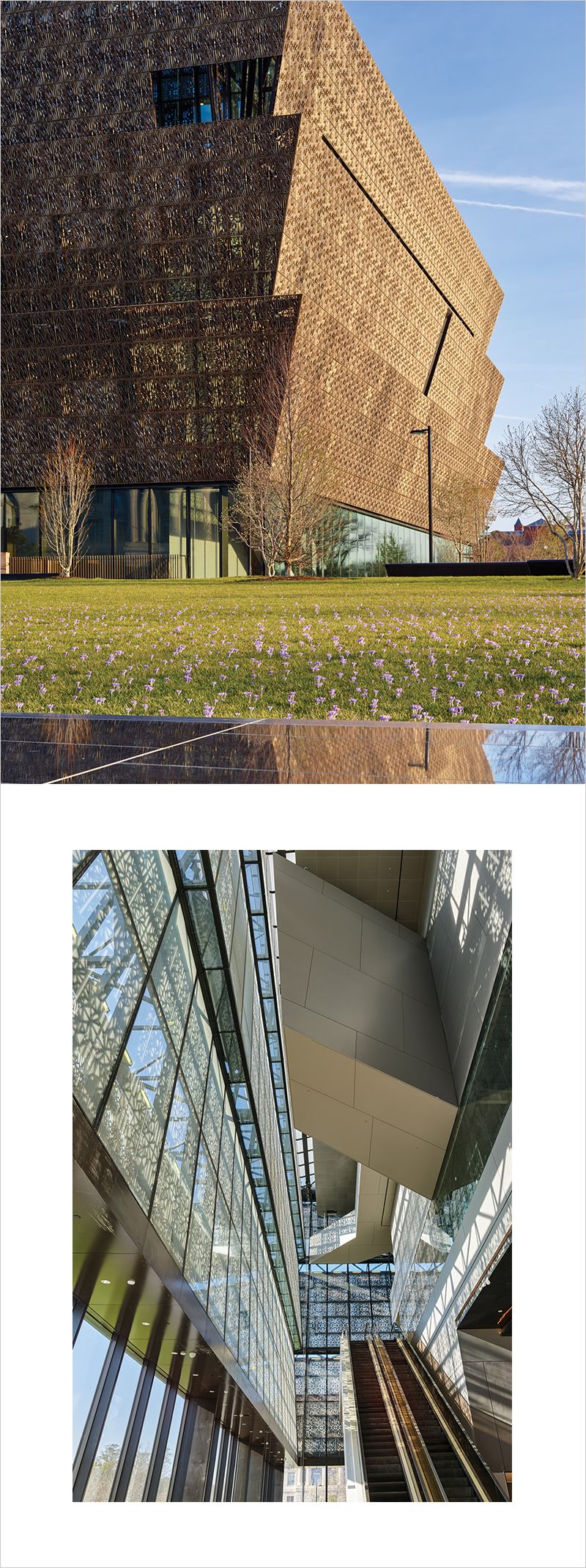

The National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington DC

Photographs by Mr Alan Karchmer. Courtesy of Adjaye Associates

Architect: David Adjaye Associates

The dark bronze finish of the filigree cladding that envelops this building is in stark and very deliberate contrast to the gleaming white marble of its neighbours on Washington DC’s Mall. This is the last major building on the US’s national museum mile and it takes its presence seriously. Inspired by the zig-zagging layers of a Yoruba crown, the building was designed by Ghanaian-British architect Sir David Adjaye and it looks like what it is: a black building in a sea of white architecture. If much of Washington’s most familiar architecture was built using slave labour, this building is a celebration of the unsung, the nation’s other history. It was finished in time (just) for the US’s first black president to inaugurate it, and its acknowledgement and display of both the pain and the joy in black history is proving a phenomenal success. Yet no matter how striking the architecture, it is the exhibits that matter more. The extraordinary, moving and often shocking artefacts of a culture that was until recently so segregated and so cruel cannot help but move. Some, like the watchtower from the notorious Angola Prison and a segregated train carriage are on an architectural scale and this big, powerful and dignified building allows them the space to speak for themselves.

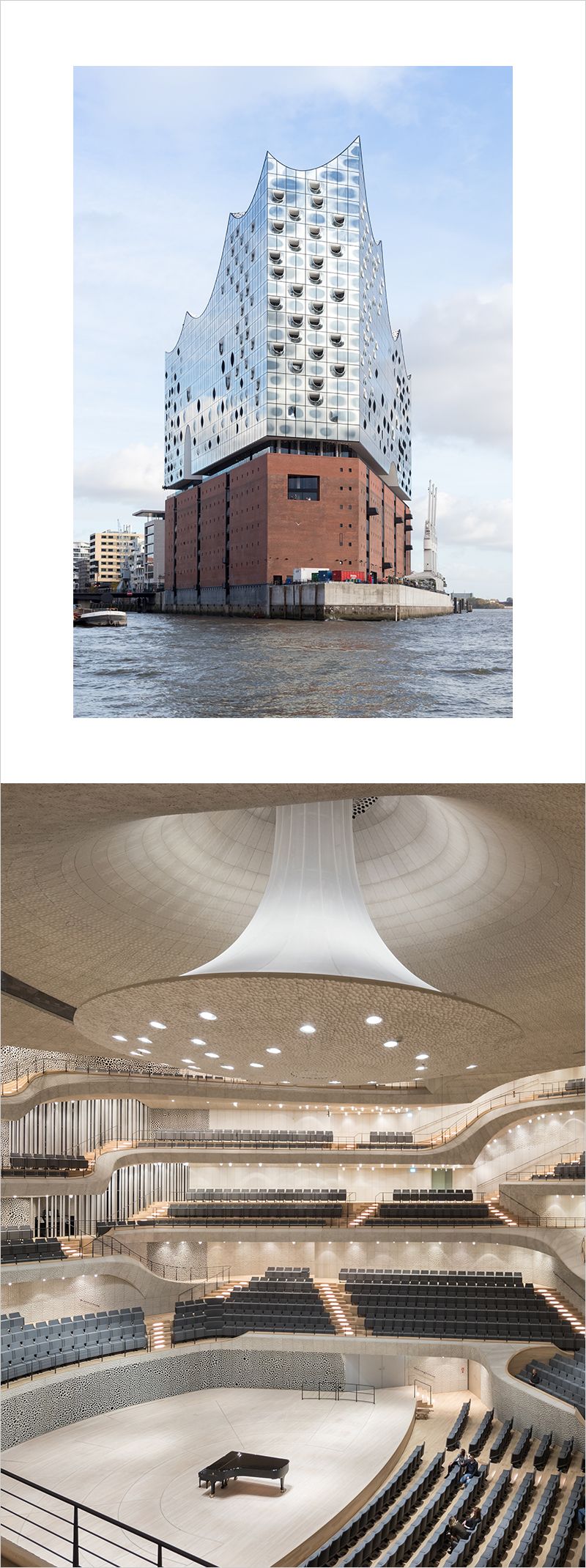

Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg

Photographs © 2016 by Herzog & de Meuron Basel

Architect: Herzog & de Meuron

This is a building that has been looming physically and metaphorically over the German city for more than a decade, even though it has only just opened. Six years late and 10 times over budget, Hamburg’s new concert hall (designed by Herzog & de Meuron, the architects behind London’s Tate Modern and its extension) has experienced a long and painful gestation. Through a constant drip of bad news, media controversies and sheer physical presence, it has inscribed itself on the city’s consciousness. After all that, it really had to be good. And it is. Stacked on top of a 1960s brick warehouse, the building, with its distinctive, sail-like glass profile, is entered via a very long escalator that incorporates a gentle curve so that it feels like climbing a hill, with the destination obscured. The upward journey culminates in an epic view over the docks and another gradual ascent through a complex, irregular interior and finally into the astonishing concert hall itself. It looks like a grotto that has been carved out of rock. In fact, that moon-like, mineral surface is an acoustic mechanism to deflect, refract and distribute sound waves throughout the auditorium. It is really quite stunning. The building is also completely open and public, a new vertical civic space for the city.

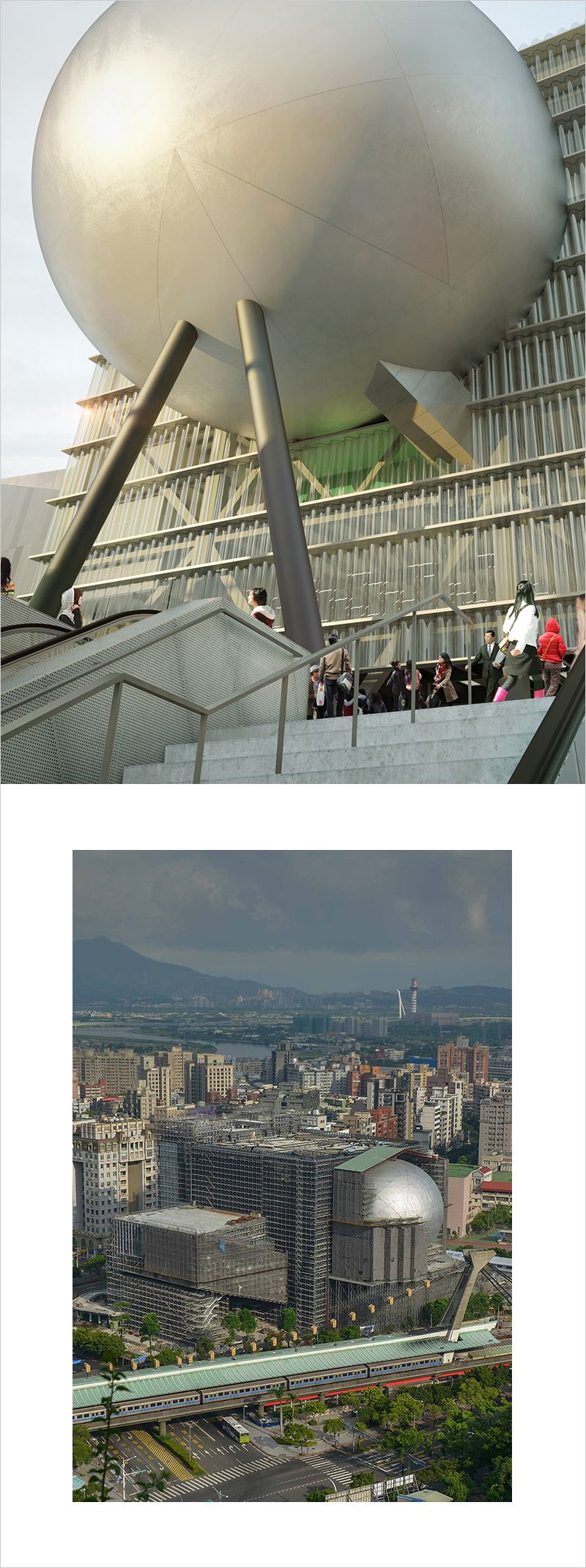

Taipei Performing Arts Centre

Photographs by Artefactorylab/OMA

Architect: OMA

Still under construction, Taipei’s Performing Arts Centre looks like some kind of urban Death Star, its spherical metallic globe emerging from the ad hoc basketwork of its very Chinese and very dense scaffolding. This is OMA’s attempt at redefining theatrical space for an unpredictable future. The three performance spaces (one of which is inside the metallic disco ball) plug in to a central backstage core. But unusually, and intriguingly, part of that backstage is open to the public and intended to be a hybrid space incorporating the industrial scale and feel of the backstage engineering with the slightly chaotic but always lively nature of the Asian street. It sounds like a fascinating experiment and is a genuinely rare departure in the world of theatre, which, despite the radical nature of what goes on stage, is often surprisingly conservative in what it builds. If you can’t get to Taipei and find yourself in England, OMA (led by architecture’s resident radical intellectual Mr Rem Koolhaas) is also building a huge new edifice for performance in Manchester. Dubbed The Factory, it will be on the site of the former Granada Studios where Coronation Street was filmed and aims to be a flexible performance space capable of accommodating anything from music festivals and opera to experimental theatre.

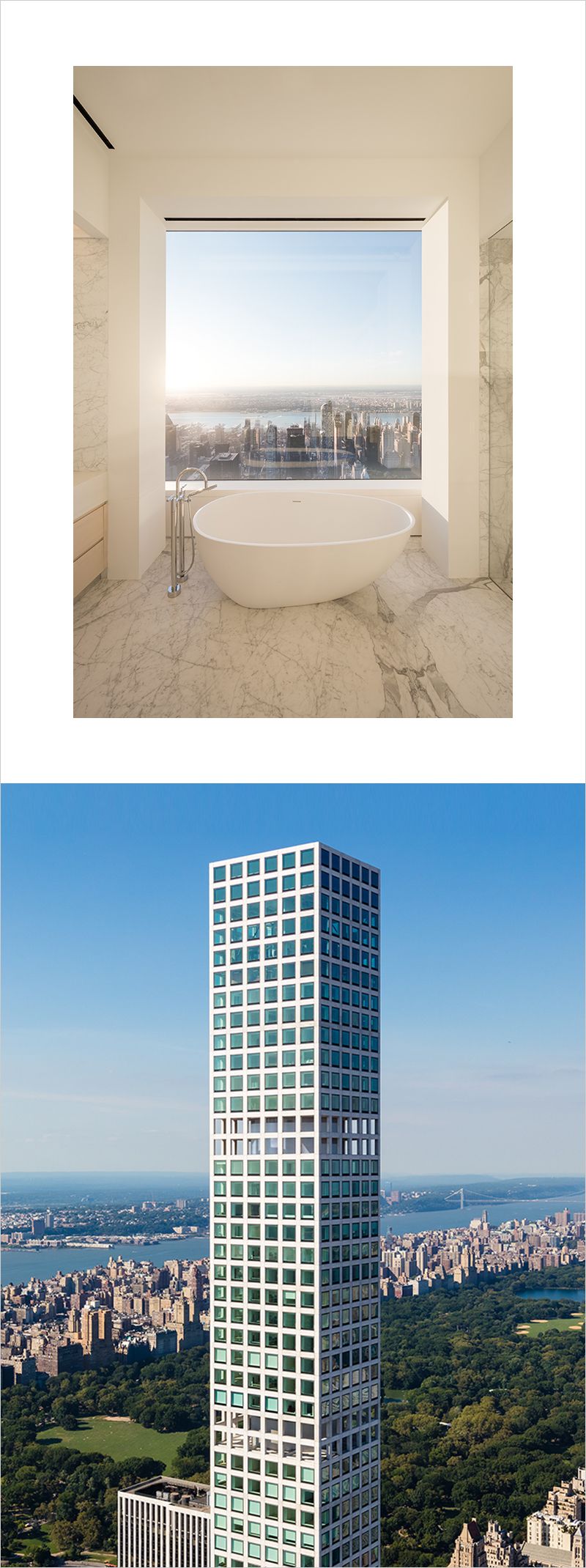

432 Park Avenue, New York

Photographs by DBOX

Architect: Mr Rafael Viñoly

When this tower started rising above its neighbours, it provoked a storm of protest. The first in a new generation of skinnyscrapers, or pencil towers, this was an architectural supermodel, tall, slender and very, very rich. The debate revolved around casting shadows on the sacrosanct green of Central Park and on whether the super-wealthy ought to be allowed to monopolise the city’s skyline. But New York’s planning regulations don’t really regulate height – it’s a dimension that can be gathered and purchased – and the result has always been the world’s most enthrallingly modern cityscape. Mr Viñoly’s tower represents something very different from the stepped profile of its Art Deco forebears, but also very different from the dim, unimaginative glass blocks that have proliferated in recent years. With its slender, extruded profile and its highly abstract grid of punched windows, there is something almost ghostly about the building. It looks like an idea or an archetype for a skyscraper made somehow real without the interference of messy construction. This kind of building, with only a few apartments on each floor, has been made possible by insane real estate prices – only a few years ago it wouldn’t have been economically feasible. It is the perfect manifestation of super-prime property, manufacturing space in the sky, but despite what it represents, it is also one of the most elegant and charismatic towers of recent years.

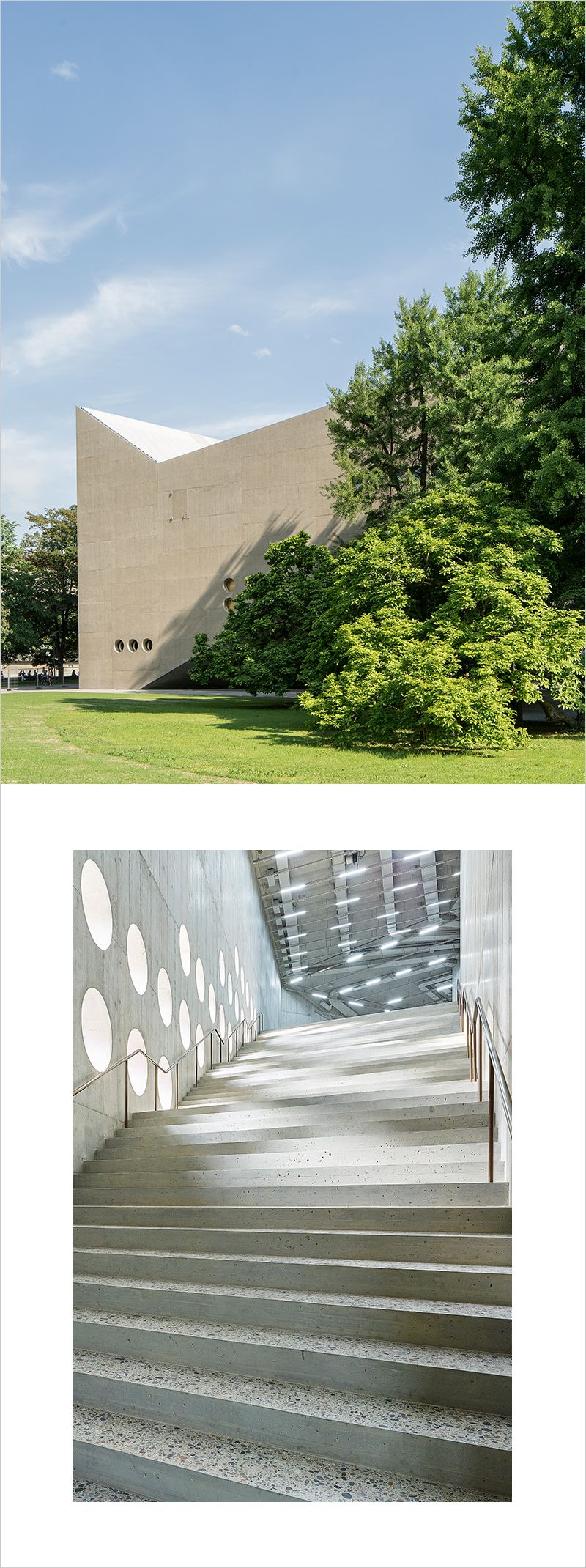

Swiss National Museum Extension, Zurich

Left: Photograph by Mr Roman Keller. Courtesy of Swiss National Museum. Right: Photograph by Swiss National Museum

Architect: Christ & Gantenbein

The Swiss National Museum is an eccentric castle, a building intended as a showcase for Swiss historical architectural styles. A little kitsch, but quite good fun, its fairytale profile defines this part of the city. Christ & Gantenbein was faced with the challenge of extending this Disneyland skyscape in a contemporary way. Its response was both brutal and brilliant. By brutal, I mean brutalist, an architecture of concrete characterised by mass, texture, structural invention and sheer scale. The zig-zagging extension acknowledges the profile of its historic neighbour in its sharp angles, but the new building becomes an architectural ECG, a jagged line that creates its own skyline as it peaks and troughs around the site. Punched with small round windows that reveal the depth and solidity of the concrete, there is something very 1970s about this, resolutely modern but with a slightly ironic throwback to a more monumental era. It is also, however, a finely crafted work and its series of interiors manages to meticulously meld the historical stone details and the new concrete surfaces. Executed with Swiss precision and an almost Brazilian sense of form, it is elegant, surprising and unmissable, a real contrast to Zurich’s more usual mild-mannered modernism.

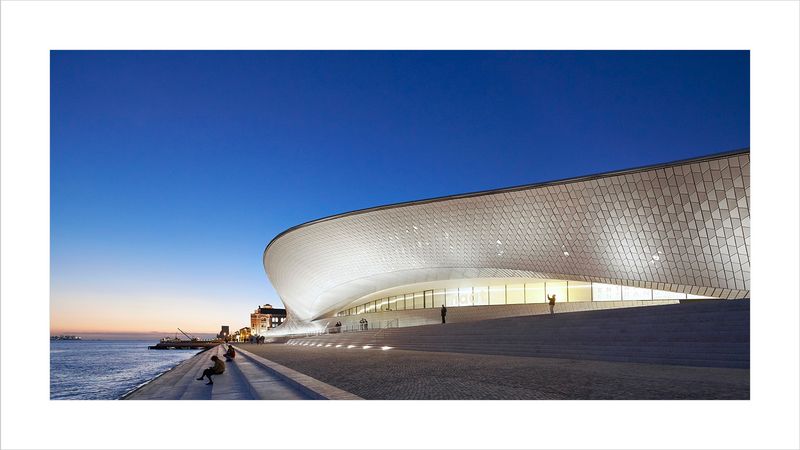

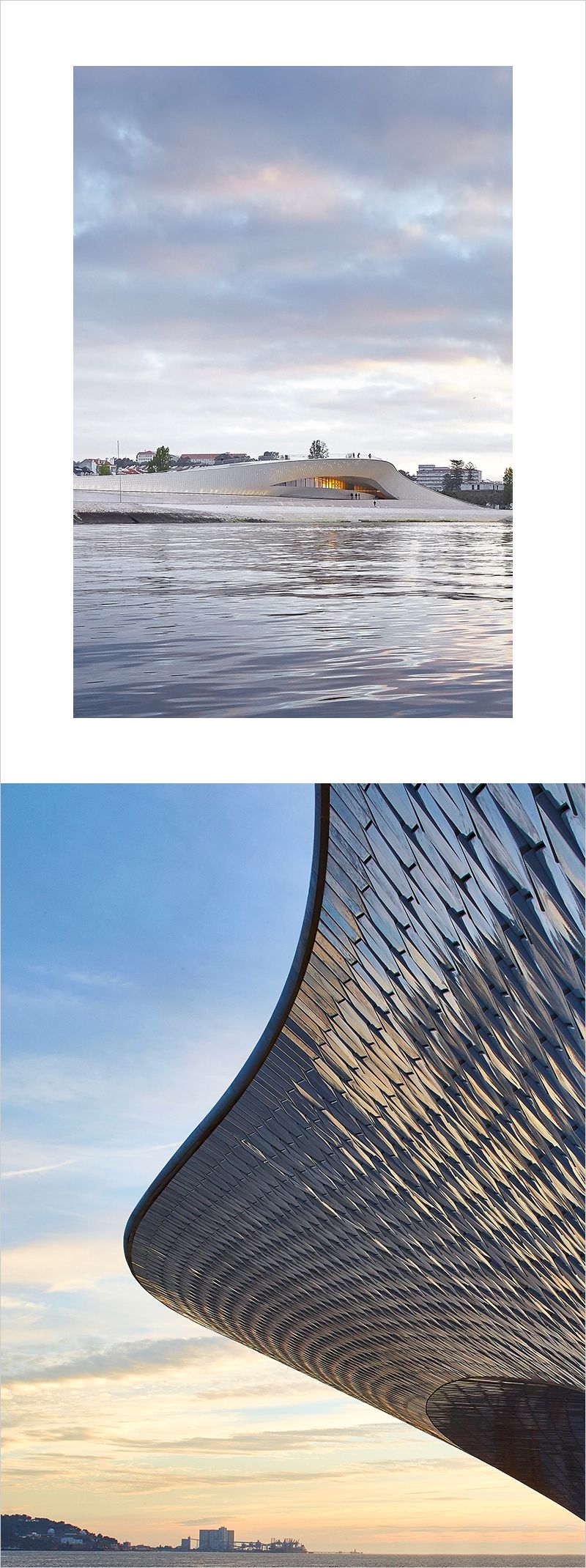

MAAT Museum, Lisbon

Photographs by Hufton + Crow. Courtesy of AL\_A

Architect: AL_A

Echoing the ripples in the grand vista of the Tagus outside, Ms Amanda Levete’s new Lisbon gallery of architecture and technology seems to be as much landscape and water as it is architecture. The gentle hump of its roof is completely accessible. Visitors and locals can – and do – clamber all over it and sit watching the boats slowly making progress towards the sea. Underneath the curve is a cavernous elliptical space, described as “Lisbon’s Turbine Hall”, a gallery that will challenge artists and curators to fill it, as well as more conventional, boxy rooms of a really serious scale. The ceramic tiles cladding the undulating exterior are supposed to echo the traditional azulejo-tiled facades of the houses that rise up the hill behind, but they also subtly reflect the coloured light from the shimmering surface of the water back into the building so that on occasion it sparkles and at twilight it glows a golden hue. Just beside the building is another impressive gallery, the Tejo Power Station (which really is Lisbon’s Turbine Hall), an art space in a wonderful early 20th-century brick structure. Just over the road is the absurdly over-scaled Coach Museum by 88-year-old Brazilian architect Mr Paulo Mendes da Rocha. This severe, massive building with its vast, empty plaza, looks like something from a sci-fi dystopia and is oddly dedicated to the fancy, gilded and curlicued horse-drawn coaches and sedan chairs that once populated the city’s streets. It makes for an utterly intriguing and delightfully strange ensemble of buildings.