THE JOURNAL

Designer Mr Giorgio Armani once remarked that “style is a simple way of saying something complex”. He was talking about clothes, but the interplay between simplicity and complexity has for centuries been at the heart of all Italian design.

Take perspective, the key artistic innovation of the Italian Renaissance. It is just the realisation that distance makes things smaller, and in an easily calculable way, but it transformed Western art forever. Much later, in the middle of the 20th century, many of the great designs were straightforward solutions to complicated problems: communal spaces could be made multifunctional if chairs would fold or stack; a minimalist approach to domestic objects, from light fittings to washing machines, could deliver elegance and utility in a single package – so long as the designer came at it with flair and imagination.

And those qualities are not the sole possession of the famed design geniuses, great names such as Messrs Ettore Sottsass, Giovanni “Gio” Ponti and Antonio Stradivari. Flair and imagination seem to be part of the national psyche. How else to explain a folk design such as the fórcola (one of the exhibits in this alternative museum) or the innumerable varieties of pasta, each one a different riff on the simple theme of flour and water? It’s a uniquely Italian thing. The scholar Mr Umberto Eco had it right when he said, “If other countries have had a theory of design, Italy has had a philosophy of design, maybe even an ideology.”

So, welcome to Mr PORTER’s Virtual Museum of Italian Design and Craftsmanship, featuring classics and creations of genius from the past 500 years, including timeless pieces from our new Italian Masters collection.

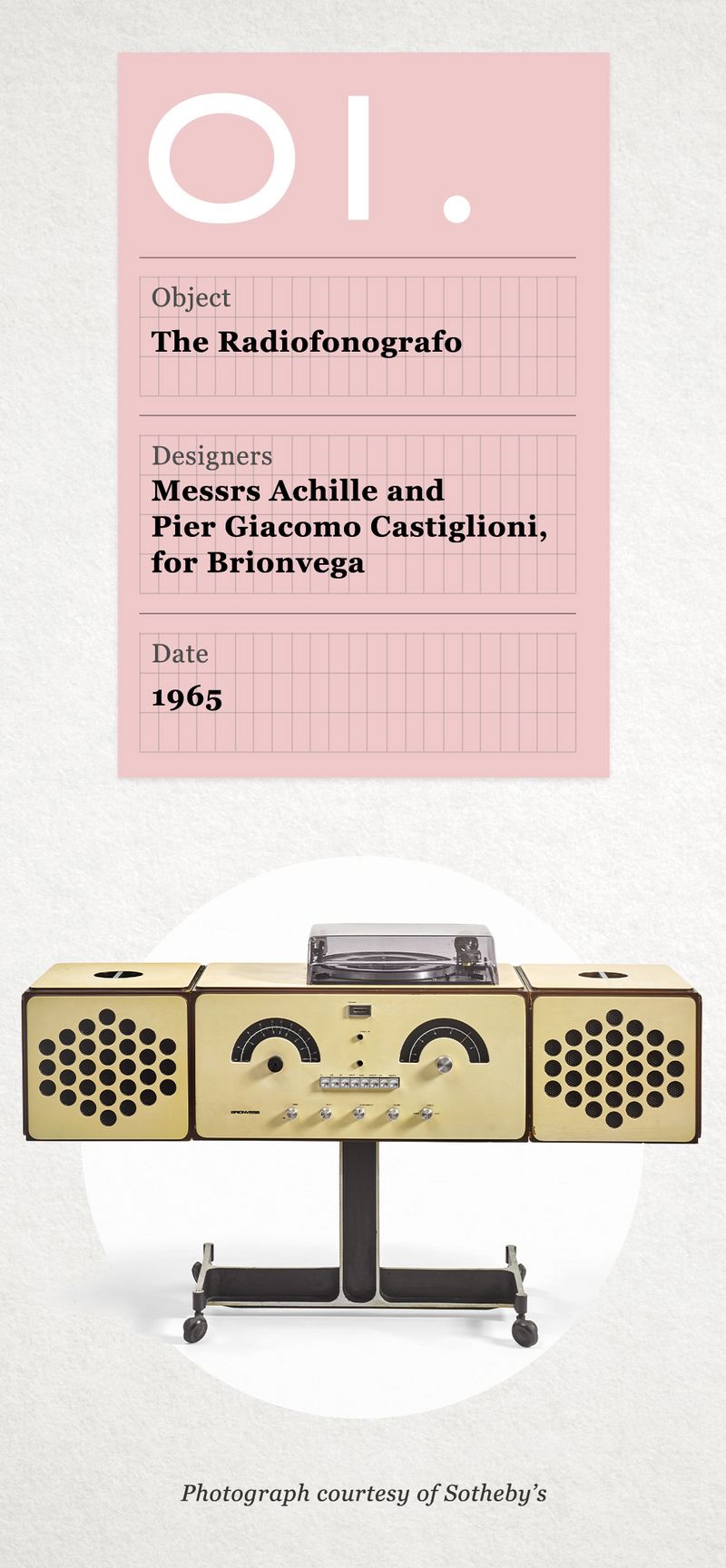

01. The Radiofonografo

The Radiofonografo was a musical robot masquerading as a cocktail cabinet. The dials and buttons that formed its “face” lent the piece a human charm while castors on its feet meant it could move around an apartment; the detachable speakers could be placed separately in a room, hooked to the sides, or stacked on top, allowing the phonograph to adopt a variety of appealing poses. Designers Messrs Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni succeeded in making a record-playing “pet”, a tangible mid-century Tamagotchi with a turntable attached.

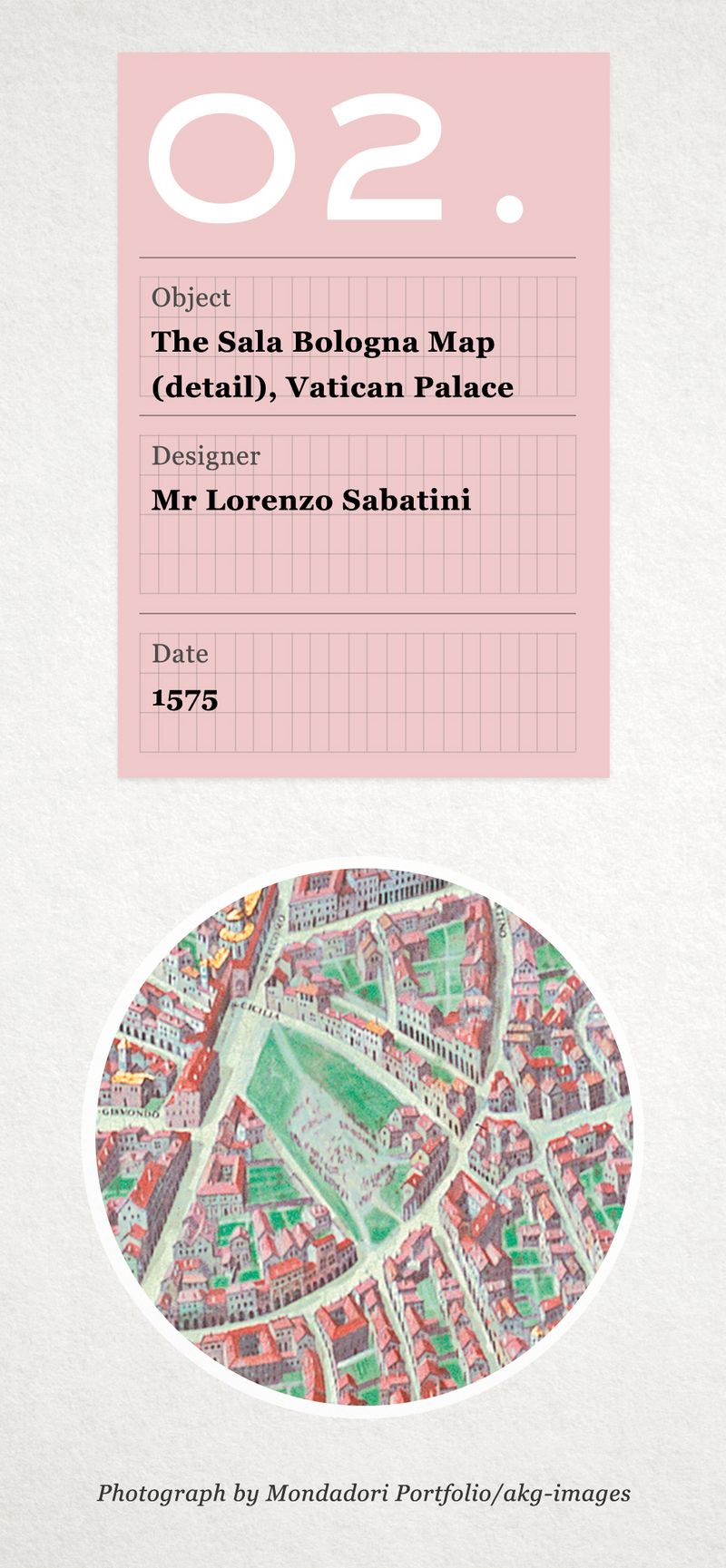

02. The Sala Bologna map

Hidden deep inside the Vatican, in the dining room of Pope Gregory XIII, is an almost 500-year-old Google Earth-style view of the city of Bologna. More than five metres across, it is a true-to-life aerial portrait of the city that the Pope grew up in. Every building and monument is represented, and the name of each street is inscribed in neat capitals. The only human presence on the map is a group in a rectangular field.

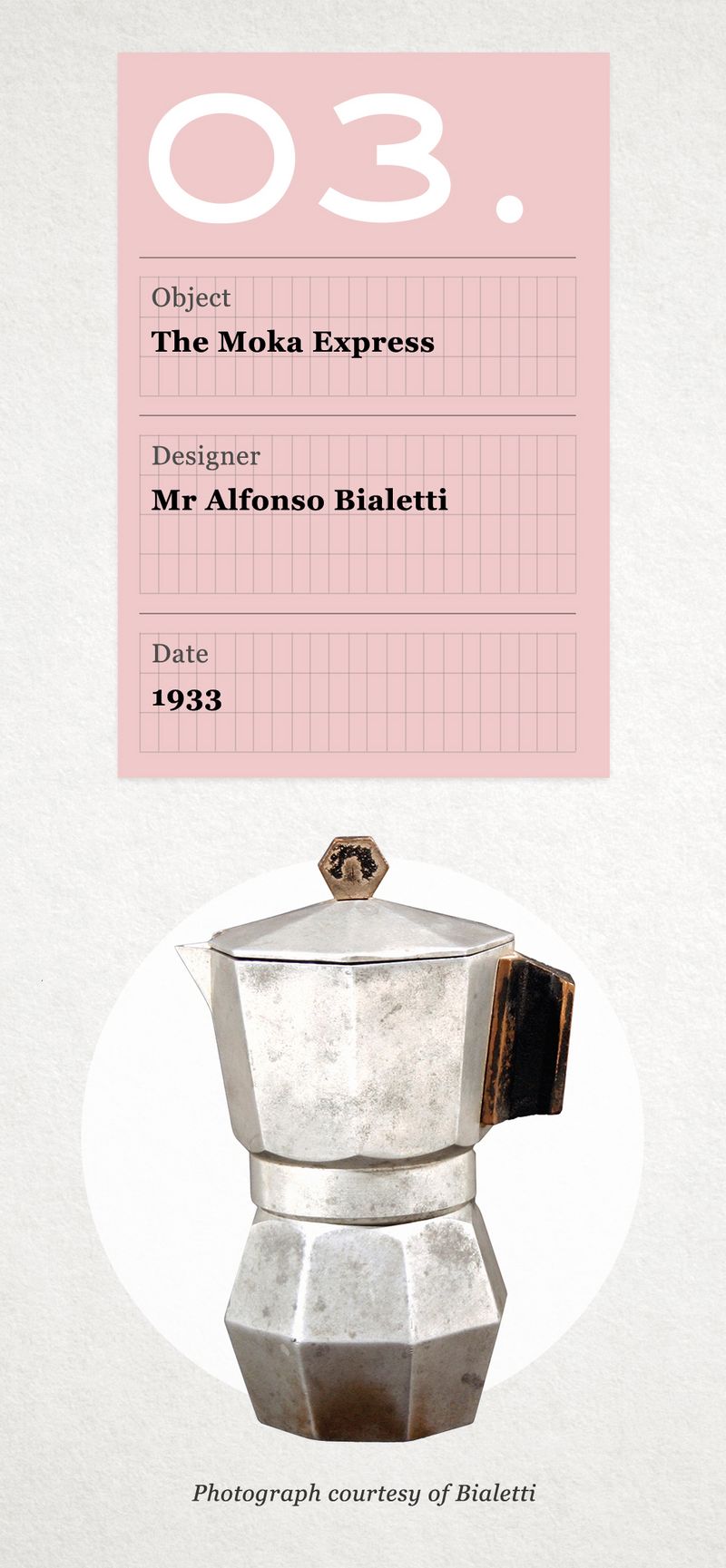

03. The angular moka coffee pot

The best method for making espresso comes courtesy of Mr Alfonso Bialetti. His stroke of genius was to use water both as an ingredient and as a working fluid. Heat applied to water in the lower chamber produces steam that drives that same water upwards, via a dense plug of coffee grounds, into the upper jug. As sometimes happens when pure utility is foremost, the object turned out to be beautiful, too. The pot is a cinched hexagon, like the torso of a bodybuilder, with a black handle looks like a muscled arm. It is a strong look for a strong brew.

04. Missoni shawl-collar cardigan

Missoni sweaters sport no visible logo, but then they don’t need to. Mr Ottavio Missoni’s signature is written into the warp and the weft. It is present in every crochet-knit chevron, lozenge, zig and zag. He described his aesthetic in the language of an abstract expressionist painter, saying that he created visual harmony by adding a third colour to two clashing ones. As every abstractionist knows, this is a difficult trick to pull off, but the shawl-collar cardigan does it. This one is inspired by sunsets viewed from the Missoni family boat – a luxurious and calming colour scheme. It is not just a masterly and instantly recognisable piece, it is also a cosy, woollen work of art.

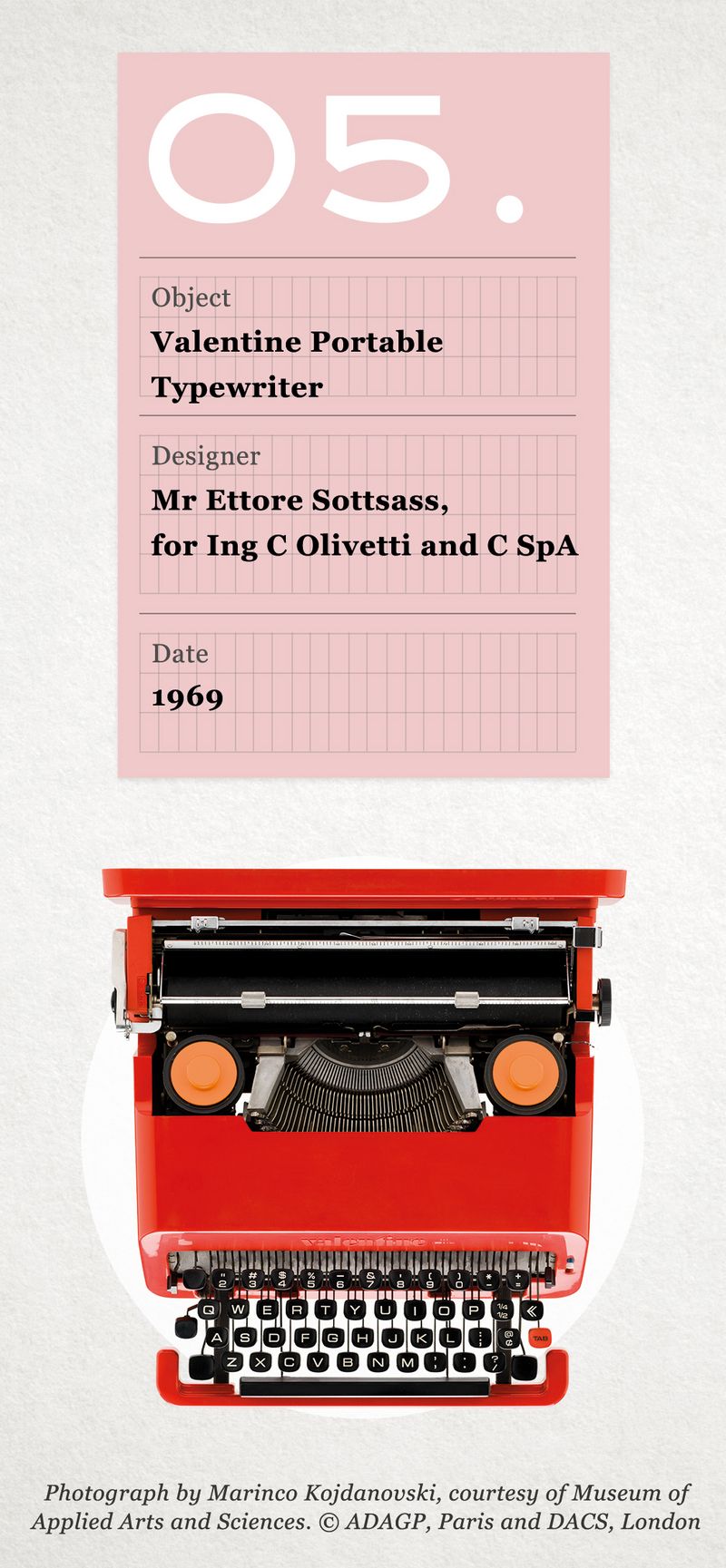

05. The Olivetti Valentine portable typewriter

Mr Ettore Sottsass set out to create a sexy typewriter. In his mind, the orange scroll caps atop the ribbon spools on the Valentine resembled the nipples of Mr Tom Wesselmann’s pop-art nudes. He wanted the Valentine to be used by wandering poets rather than office drones or fat-fingered policemen. Every element of his portable machine had the same liberating intent: the case that could serve as a makeshift seat or as a bin for first drafts of anguished love lyrics; and (though Olivetti vetoed the idea) keys that printed only capital letters. The production model came in various colours and had an inbuilt handle; it is recognisably the analogue ancestor of the fruit-coloured clamshell iBook.

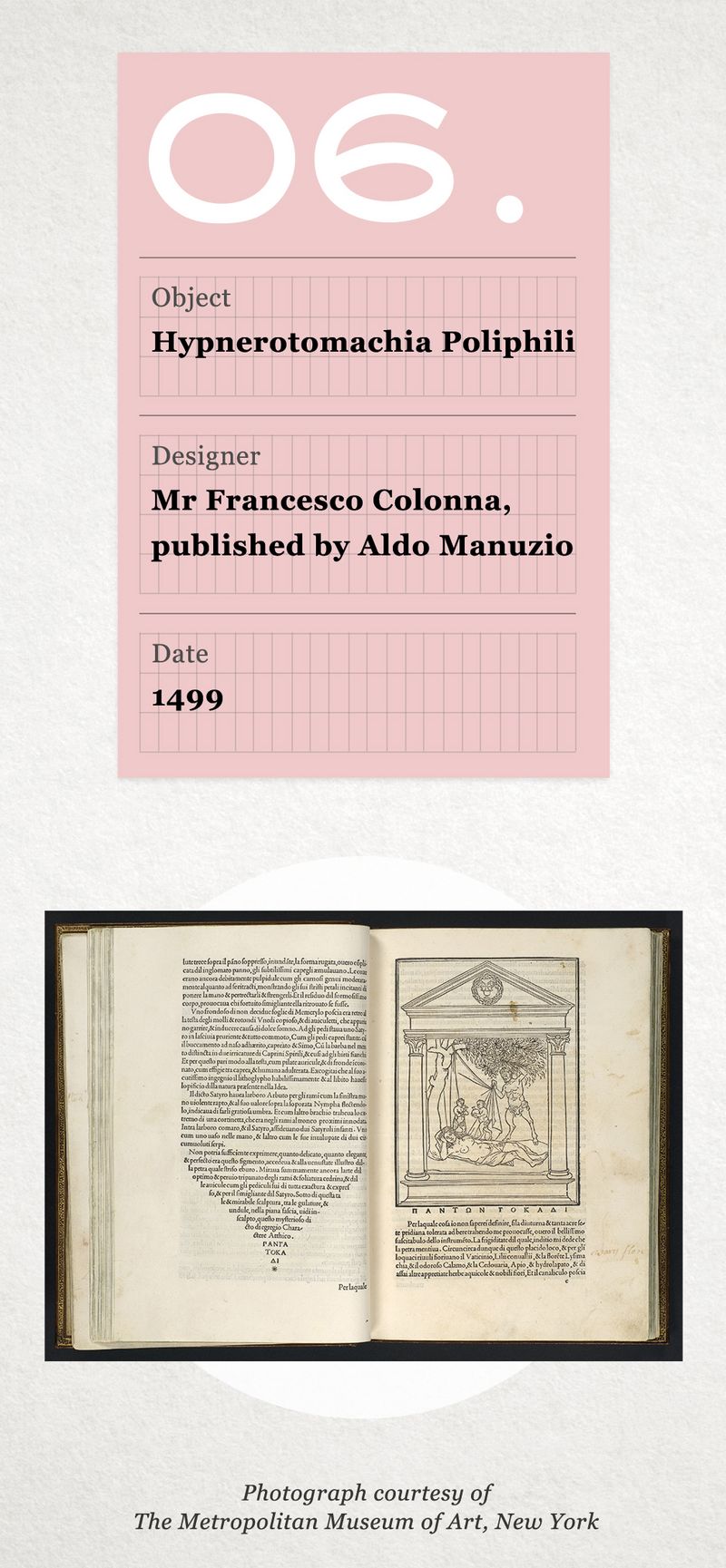

06. Mr Aldo Manuzio’s proto-paperbacks

Half a millennium ago, Mr Aldo Manuzio (otherwise known as Mr Aldus Manutius) was the first publisher to make books that would slip into any pocket. In other words, he made knowledge portable and accessible. In the last years of the 15th century, it’s estimated that a third of the world’s books came out of Venice: the late-medieval Silicon Valley, if you will. Mr Manuzio understood that the new printing technology required novel forms of presentation. He transformed punctuation, introduced italics and page numbering, brought in design principles such as white margins and proportional point size. And, when he felt like it, he played whimsical visual games with the text.

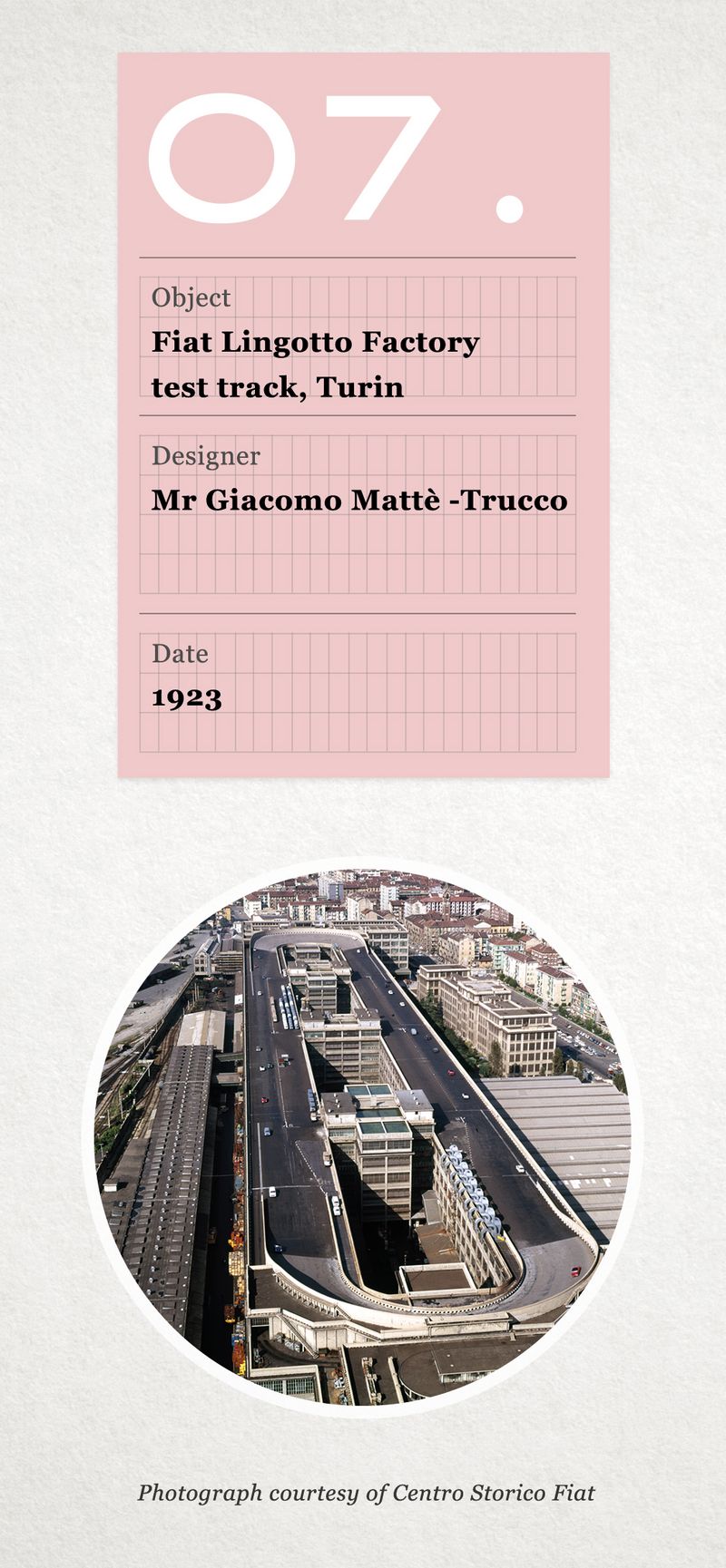

07. The rooftop racetrack of the Fiat factory

The track on top of the Fiat factory in Turin looks like it was made for chariot races: it echoes the form of the Circus Maximus in Rome. This high road is the elevated last lap of a production line that is coiled like a spring inside the factory building. For more than 60 years, raw materials came in on the ground floor, where they were shaped and assembled on a line that wound its way up five storeys. The finished cars emerged into the sunlight on the roof, where they were test-driven before heading back down the ramp and out to the showroom.

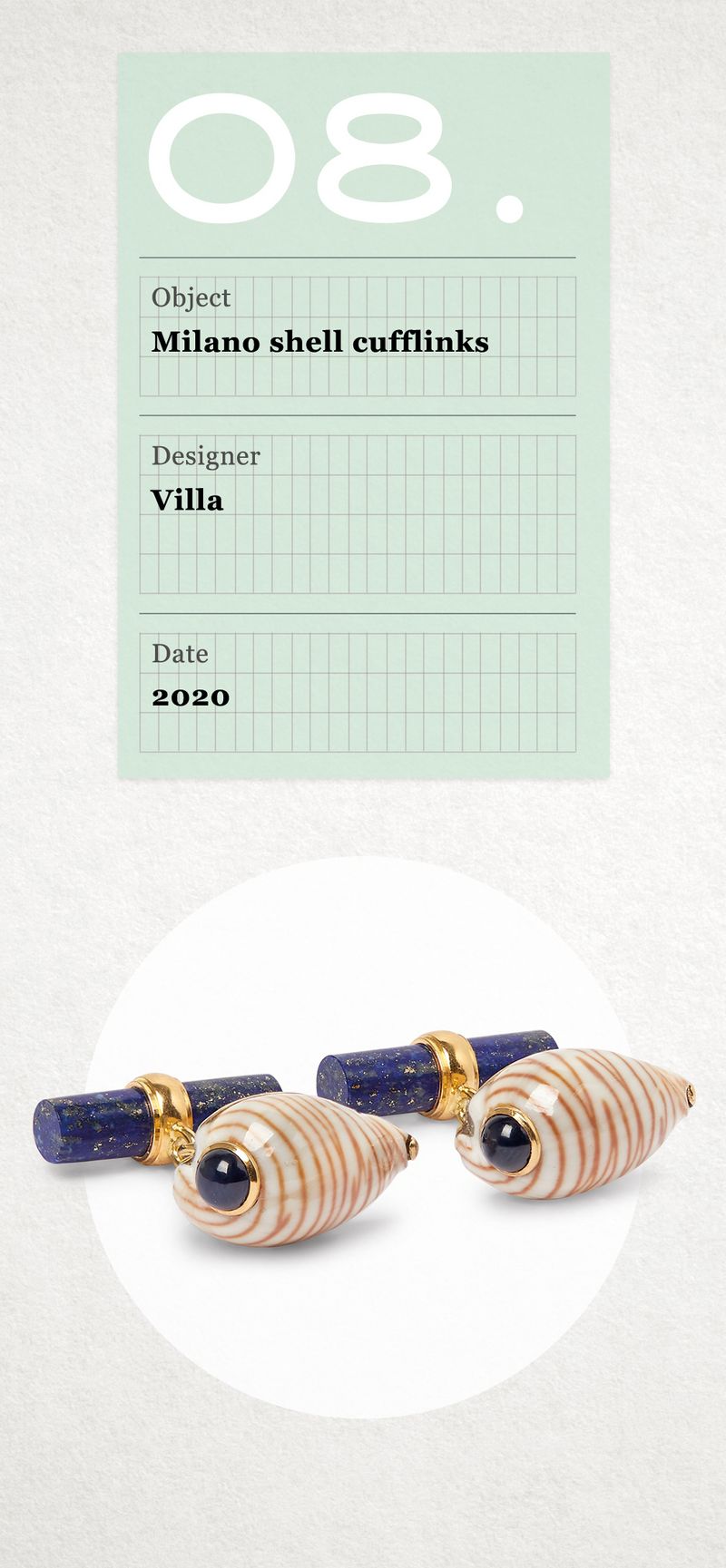

08. Villa shell cufflinks

Cufflinks are the most subtle way for a sharp-suited man to express himself, because they are both essential and infinitely variable. Villa crafts countless cufflinks that nod at a passion or tell a joke – drumsticks in yellow jasper, or a coral cabriolet with diamond headlights. But the mother-of-pearl shells are perhaps the most stylish option. Nerites, cone snails and striped marginella are paired with bars made from lapis lazuli, onyx or agate. So, the cufflinks are part-mollusc and part-mineral – they have something of the rolling sea in them, and something of the rock-hard earth.

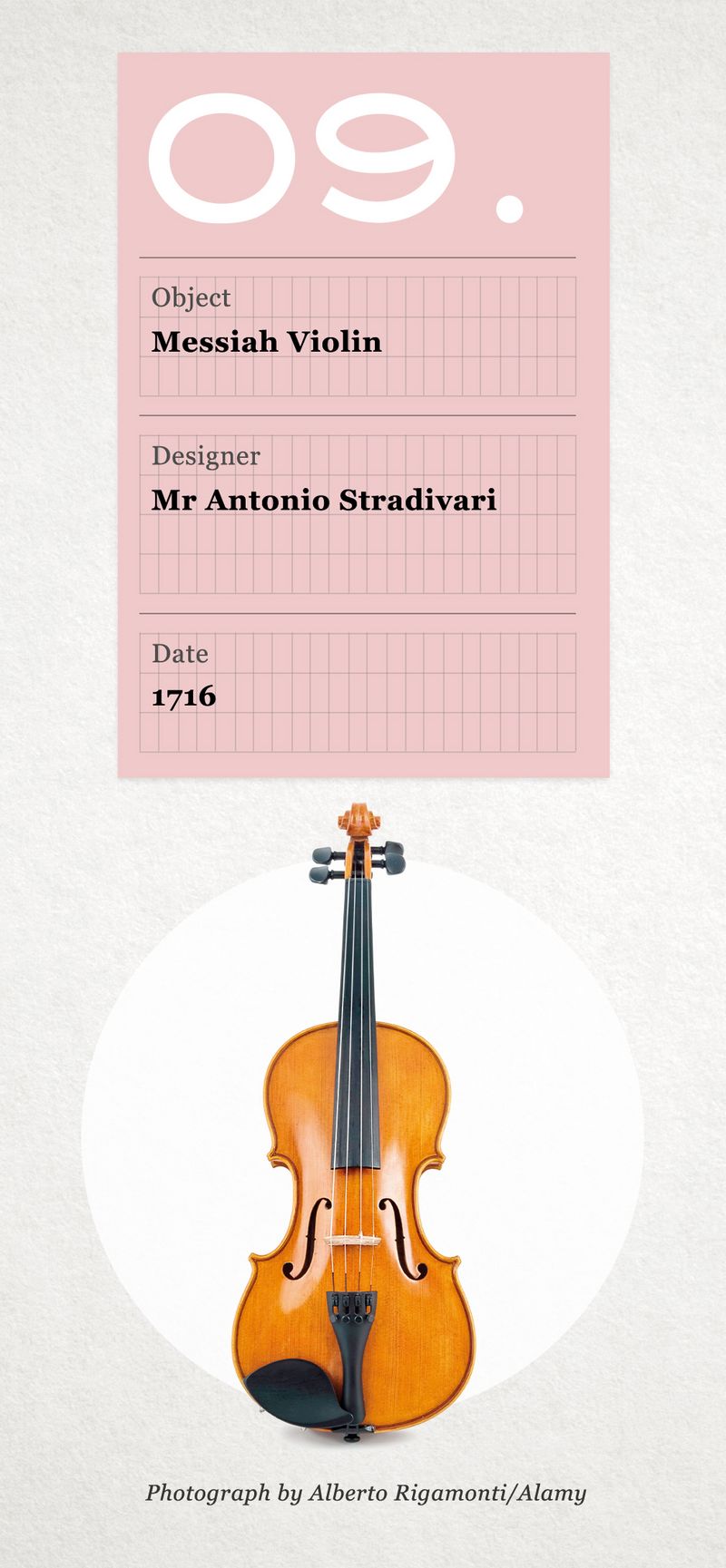

09. The Stradivarius Messiah violin

Modern experiments have shown that the greater the circumference of a sound hole on a string instrument, the better the sound – but there is little room for holes on the face of a violin. The F-hole, developed by the famed luthiers of Cremona and refined by legendary maker Mr Antonio Stradivari, is the solution to that problem. The shape seems to derive from three-dimensional geometry. Imagine a sphere, neatly peeled in one piece from top to bottom; laid flat it would make the template for this long and supremely graceful curve. It is the long, leading edges of the sinuous F-holes that make a Stradivarius sing.

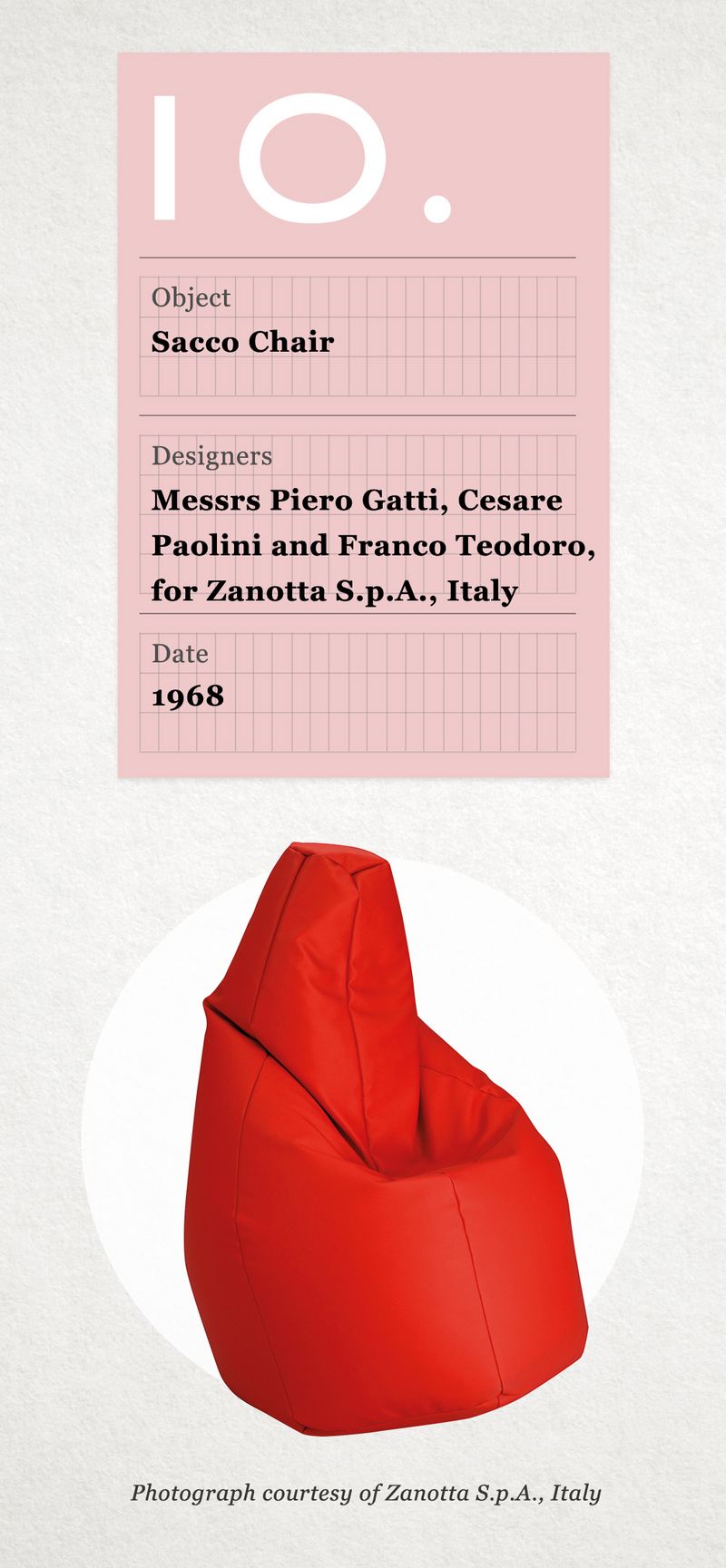

10. The Sacco chair

Better known as the bean bag chair, the Sacco was an anti-chair, the strange love-child of a barstool and a pillow. It did away with the conformist, stiff-backed tyranny of chair-ness by making it impossible to sit up straight. You could only lounge, be a slob in a blob, and that made the Sacco the seat of choice for hippies everywhere. It was designed by Messrs Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini and Franco Teodoro. They were like a briefly shining boy band – they produced this one hit and nothing else of note – but their chair was much copied and lives on in break-out rooms from Shoreditch to San Francisco.

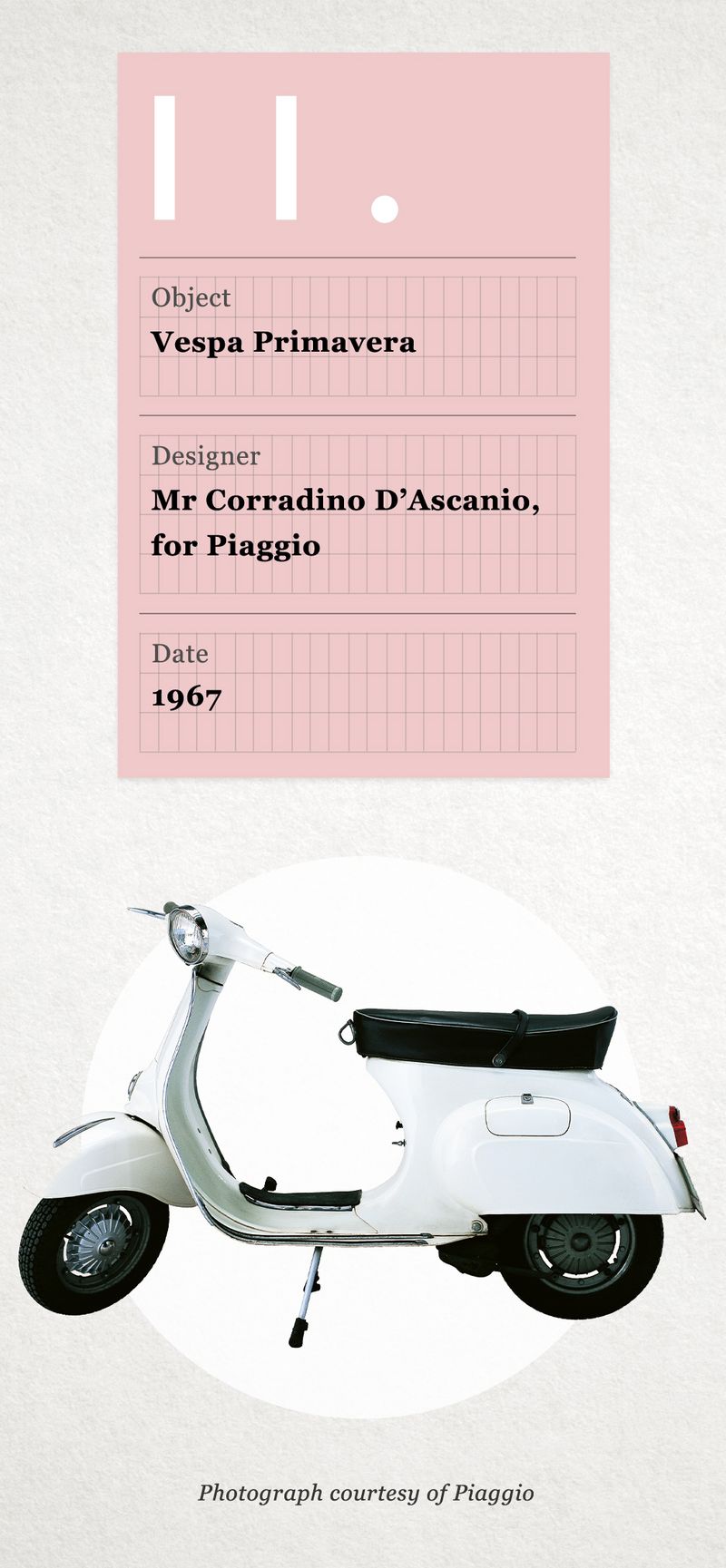

11. The Vespa Primavera

The Primavera was by no means the first Vespa – versions had been in production since 1946 – but it was the model that turned the scooter from a two-wheel mule into something that betokened joy, youth and liberty. That was all down to the reconfigured seat on its long chassis, which made it possible for two people to ride together – so long as those two people were happy to cling tight to each other. The “spring” was, in other words, 121cc of pure romance – and it hit the market just in time for the summer of love.

12. FPM Milano Cookstation

If you were to ask the people behind the Swiss Army knife to brainstorm a kitchen, they would be hard-pressed to come up with something more crazy-brilliant than the FPM Milano Cookstation. Conceived by Milan-based designer Mr Mark Sadler, it is a piece of portable luggage containing an oven, stove, fridge and worktop, all of which unfurl like butterfly wings from the inside of an upright wheelie suitcase. Almost unbelievably, there is room in there for a fully functional batterie de cuisine: knives, pans, wooden spoons, casserole. It is a glamping miracle in an aluminium box, a micro-cucina in which every ingredient is reduced like a red-wine jus, until all that’s left is what’s essential.

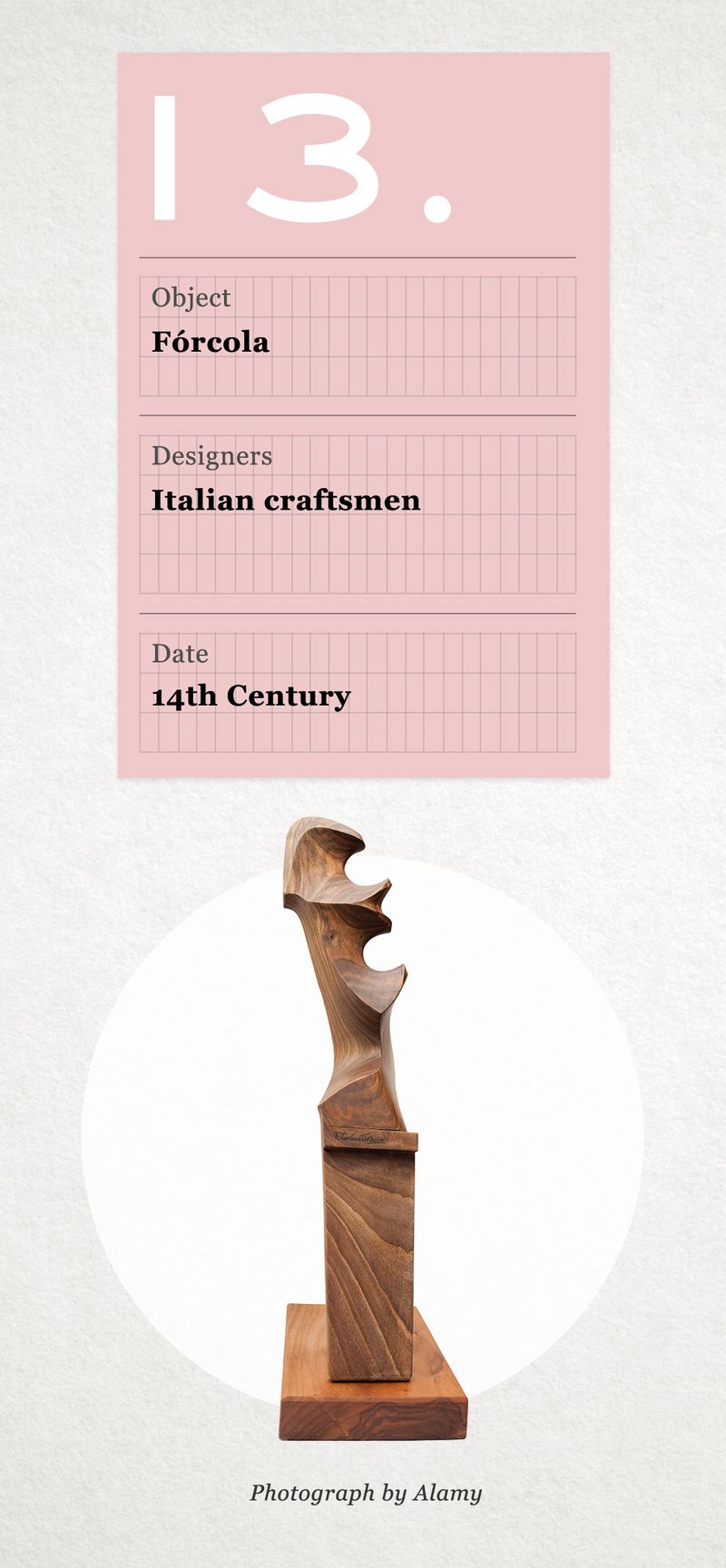

13. The fórcola (rowlock) on a gondola

The fórcola may look like a lost sculpture by Mr Constantin Brâncuși – but it is in fact a masterpiece of maritime engineering. In conjunction with a long oar, it functions as the steering column and the wooden gearbox of a Venetian gondola. Every notch and twist facilitates a different oaring position and discrete manoeuvres: driving forward, reversing, tight turning, moving off and so on. And every fórcola is unique – not just because they are the works of individual masters, but because each must take into account the height and weight of the specific gondolier who will use it: a handmade fórcola is as tailored and individual as a bespoke pair of shoes.

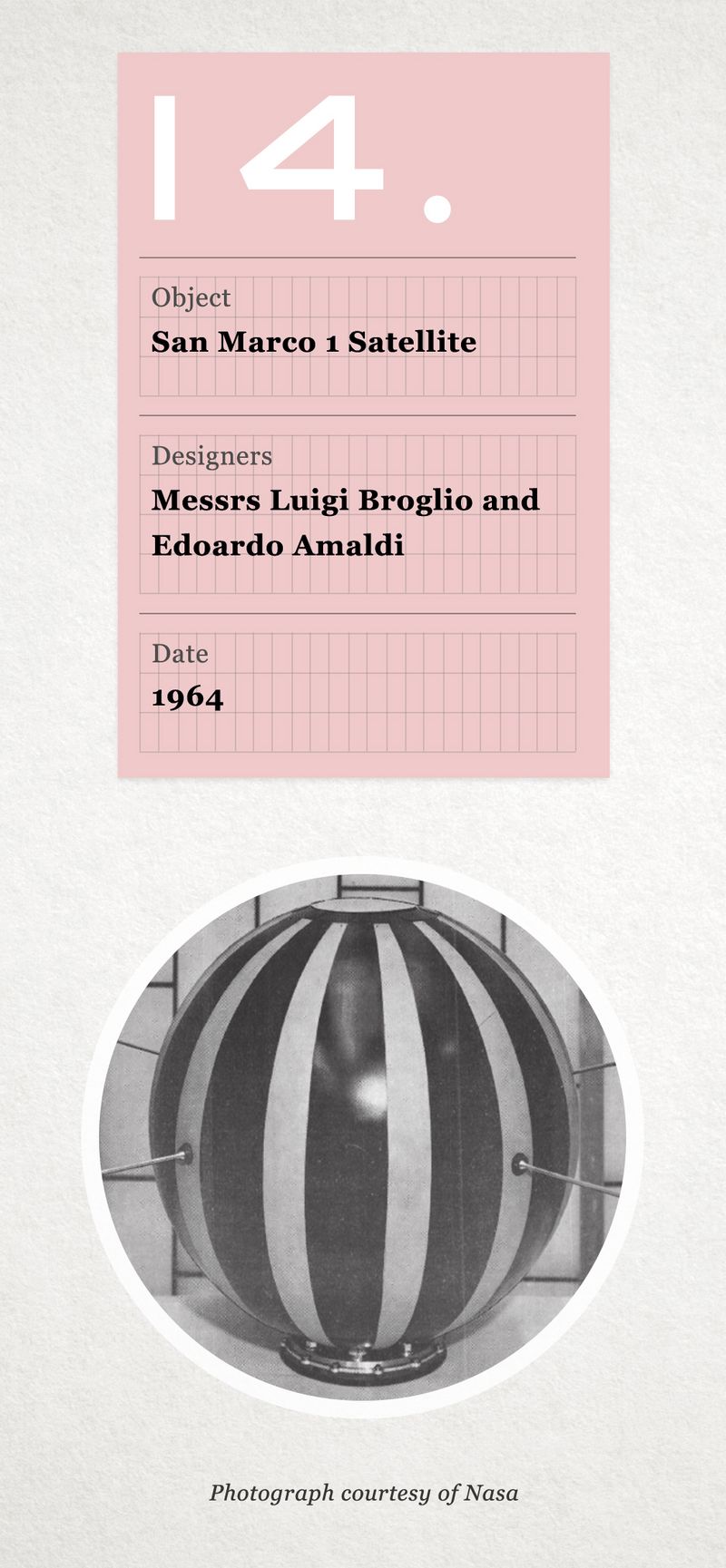

14. The San Marco 1 satellite

When San Marco 1 went into orbit on 15 December 1964, it instantly became the most stylish thing in space. Italy’s first satellite, built and launched by Italian scientists, was as smooth and polished as the fairings on a Ferrari. The theatrical black and white stripes lent it a kind of commedia dell’arte vibe, as if Italy had gone to space in Pedrolino’s trousers. Like many fashionable items, the San Marco was short-lived. It turned around the planet until September 1965, then burned up in a blaze of glory as it fell back down to Earth.

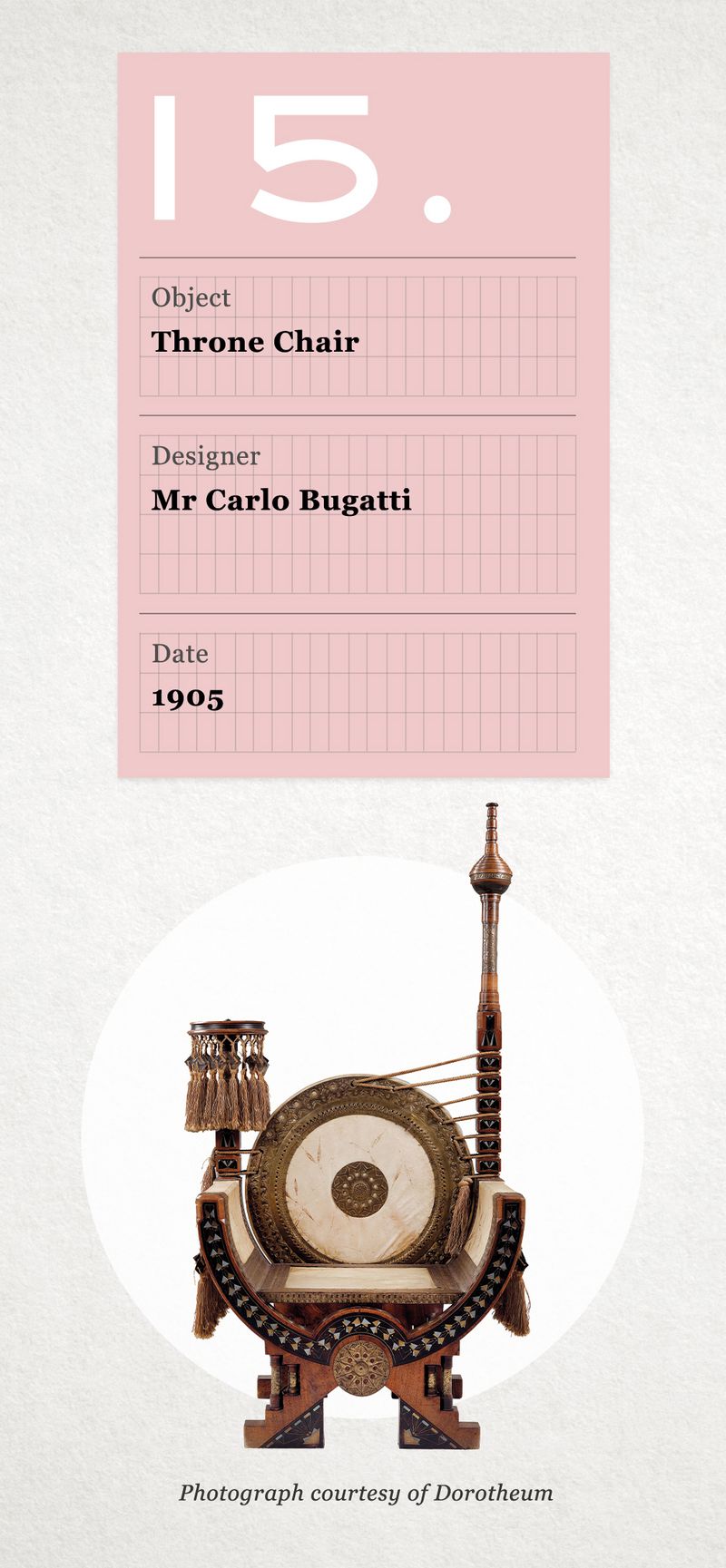

15. The Bugatti Throne chair

Mr Carlo Bugatti’s Throne looks part-Moorish, a bit Japanese, kind of Egyptian. It is an eclectic chair, the product of a unique artistic sensibility, but it could also be an artefact from some lost and ancient civilisation; the lettering on the stretcher-back belongs to no known alphabet. Something about this idiosyncratic, asymmetric style appealed to an English sensibility; the furniture sparked huge interest in fin-de-siècle Britain. Mr Bugatti produced little in the latter part of his life, but bequeathed a flair for design to his son Mr Ettore Bugatti, who made cars.

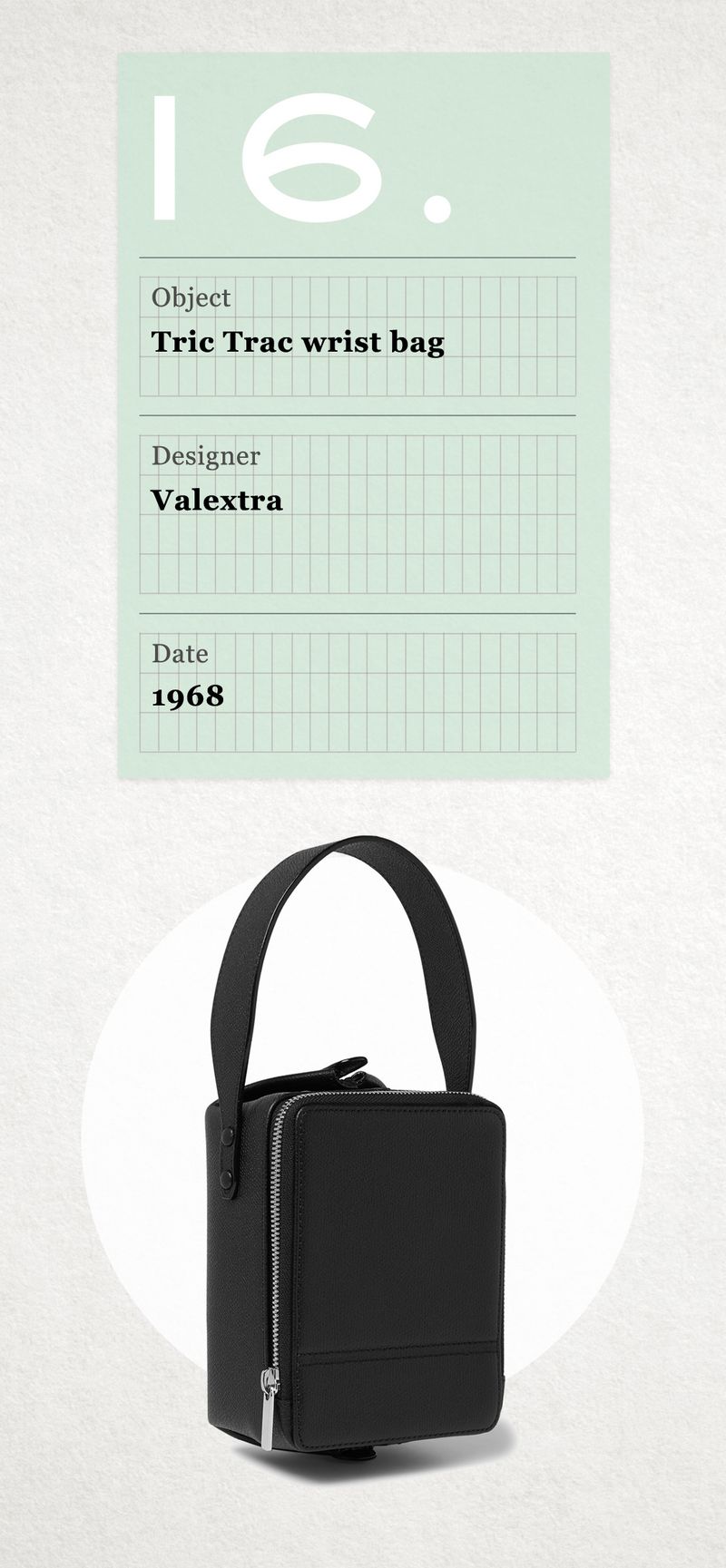

16. Valextra Tric Trac bag

Nothing ruins the line of structured jacket like a bunch of car keys in the pocket. In 1968, Valextra’s founder Mr Giovanni Fontana envisaged the Tric Trac as a receptacle for all the objects that tend to spoil a man’s silhouette. Back then, the paraphernalia of modern maleness was slightly different: a soft pack of Gitanes, little black address book, stub-cheques and a money clip. But the beauty of the boxy camera-case Tric Trac is that, half a century on, it seems purpose-built to hold a smartphone, a small water bottle and a tailored face mask. It is, in other words, an unreprovable object, an Italian design classic.

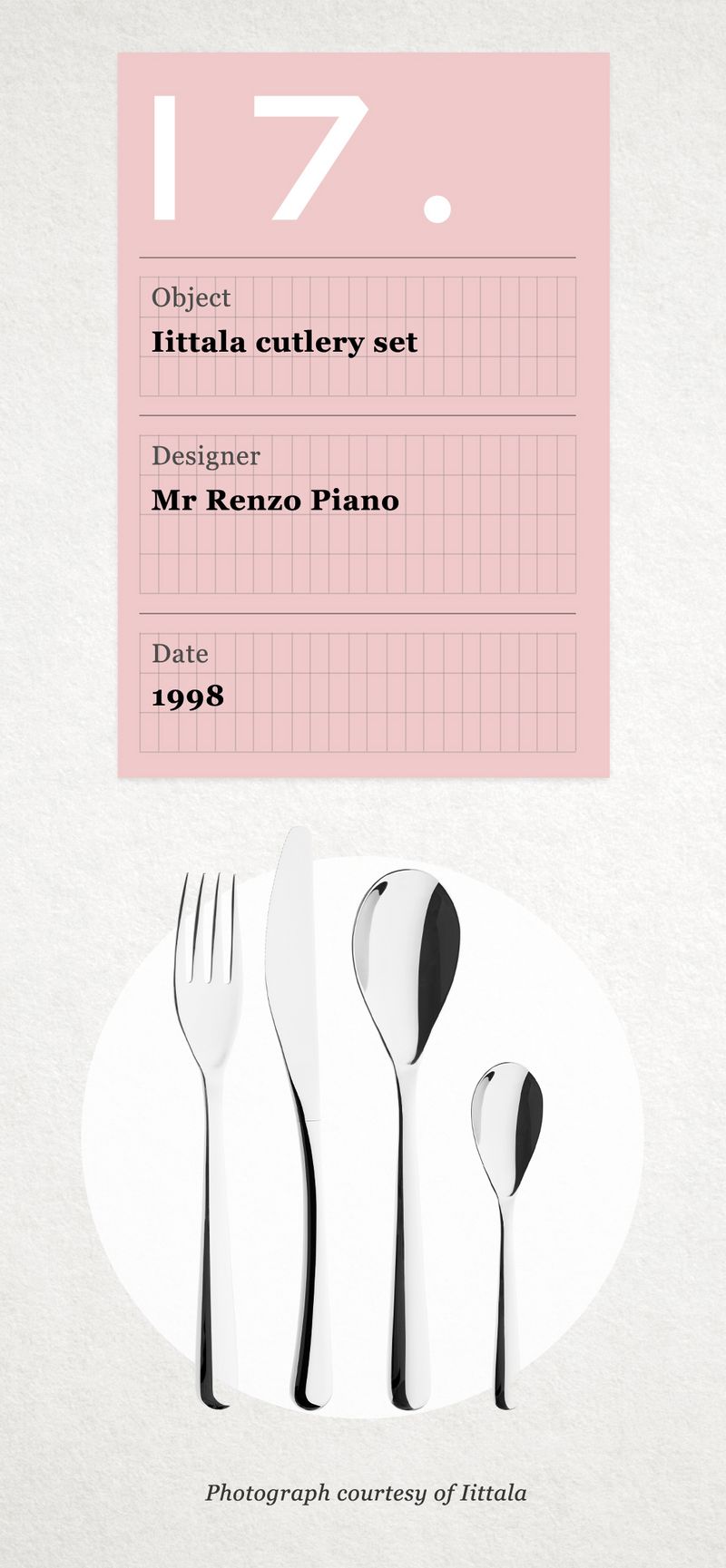

17. Mr Renzo Piano’s Iittala cutlery set

Architecture is all about volume; cutlery usually isn’t – which is why they call it flatware. When the architect of the Pompidou Centre in Paris and The Shard in London turned his hand to forks and spoons, he made the handles hollow like a room. The idea was to balance the weight while allowing the pieces to sit in the palm like the wooden haft of a carpenter’s favourite chisel. So, these are domestic tools conceived in three dimensions – machines for eating with, as Le Corbusier might have said.

18. The Lamborghini logo

In 1963, when Mr Ferruccio Lamborghini switched from manufacturing tractors to fast cars, he chose a badge for his marque that was a veiled self-portrait: his star sign was Taurus and he had a passion for bullfighting. That heraldic shield, a rivalrous echo of Ferrari’s logo, suggests that a sports car is both the steed and the armour of a modern-day knight errant. As for the golden bull – head down and ready to charge – it expresses everything that the Italian automotive tradition stands for: latent power, the thrill of competition, the pleasures of wealth and a very particular machismo. It is an entire petrol-driven philosophy in one graphic and memorable image.

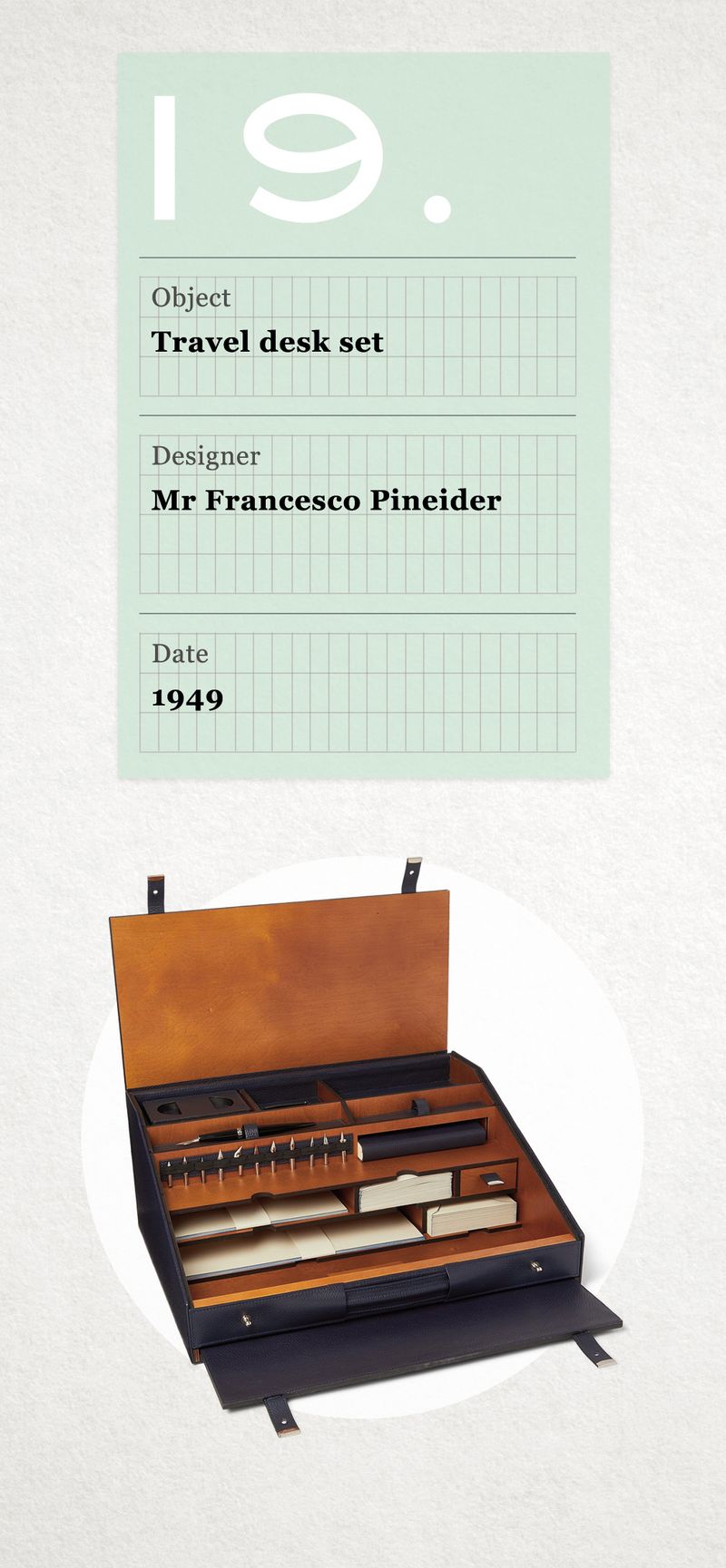

19. Pineider travel desk set

Globetrotting and writing are two activities that require a sense of style. Mr Francesco Pineider understood this at the very dawn of the age of leisure travel. Three centuries ago, his _cartoleria _(stationery shop) on the Piazza della Signoria in Florence counted Mr Charles Dickens, Stendhal and Lord Byron among its customers, while the outpost in Rome caught the eyes of General Gabriele D’Annunzio and Dame Elizabeth Taylor. The travel desk set, which came a little later, is Pineider’s sumptuous masterpiece. It is an analogue laptop wrought in calfskin and cherrywood, a toolkit for writers and thinkers who know that that is hard to put down bad prose on deckle-edge water-cut notepaper.

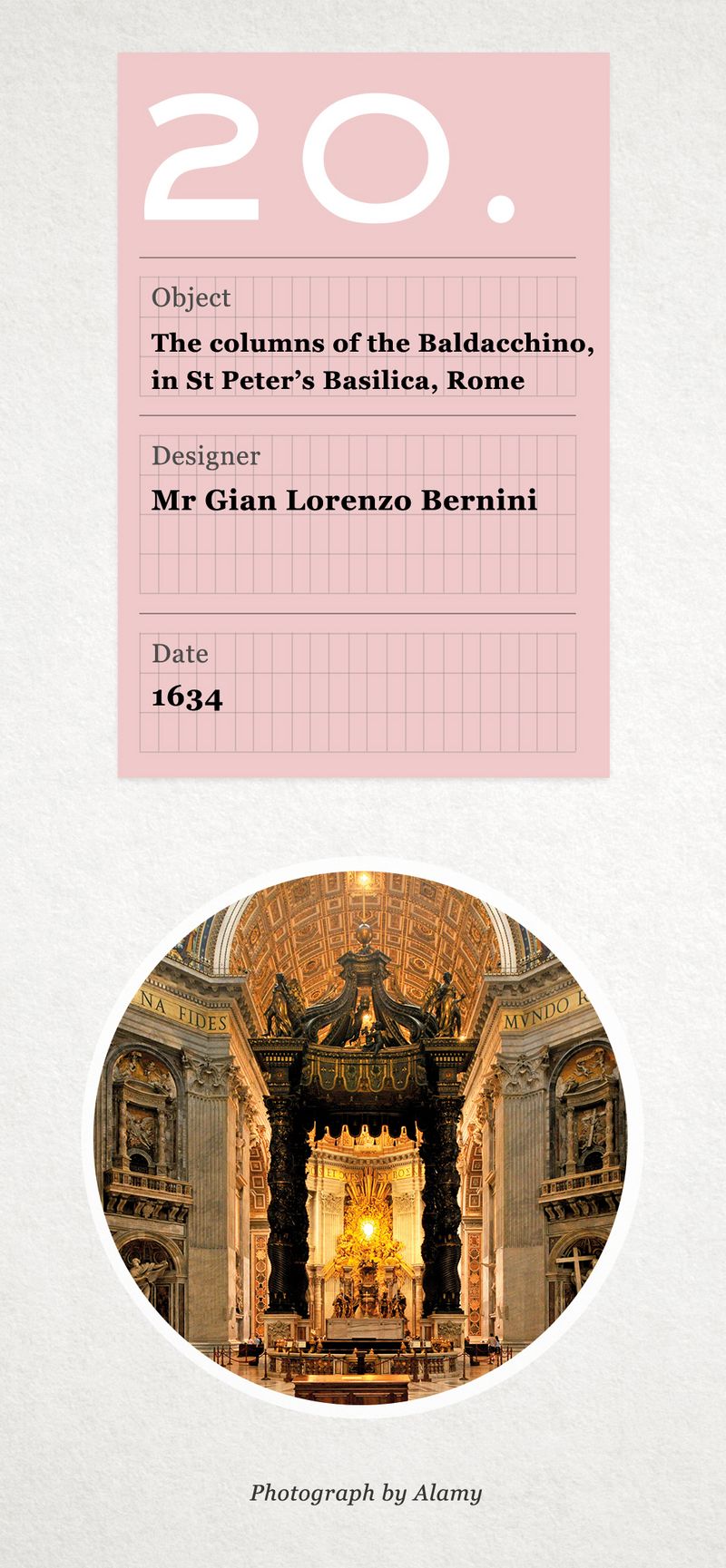

20. The columns of St Peter’s Baldacchino

Helical or “Solomonic” columns are a signature feature of baroque, the quintessentially Italian architectural style. Mr Gian Lorenzo Bernini deployed them in the canopy that covers the site of St Peter’s grave in Rome. Those elaborate tentpoles then took on a life of their own, migrating to other countries and decorative settings. They became French table legs, the barley-sugar pillars flanking the dial of English grandfather clocks, fluted candlesticks on Dutch sideboards. Everywhere, for centuries after Mr Bernini, they have been an unstated Italian twist in other people’s design ideas.

MR PORTER has partnered with the Fondazione Cologni dei Mestieri d'Arte to support the Foundation’s annual “A School, A Job. Training to Excellence” apprenticeship programme, which matches 25 Italian graduates from a selection of the best schools and universities of Arts and Crafts with 25 Italian artisanal ateliers or businesses. The theme of this year’s apprenticeship is “Renaissance and Sustainability”; it is seven months in length and comprises of one-month university training in Milan, followed by six-months on-the-job experience.